Pharmaceutical companies present ads and commercials of men climbing a mountain or running a marathon while they are taking the latest approved HIV medication. People think that one pill is going to allow them to run marathons and climb mountains, not knowing that there are horrendous side effects, that drugs don't work for everybody, that people are developing neuropathy, diabetes, liver and kidney problems, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, and a whole laundry list of side effects that are debilitating and often kill people far earlier than someone would die if they weren’t HIV infected and getting these complications that are caused by the drug’s side effects.

Eric Sawyer

Download interview in PDF format ![]()

An Interview with Eric Sawyer

March 1, 2011

Eric’s office at UNAIDS in New York City

Eric Sawyer: I am Eric Sawyer. I am a co-founder of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in New York, of an organization called Housing Works that houses homeless people with AIDS, and of an organization called Health GAP (Health Global Access Program), which does advocacy around HIV and access to essential medicines. I now work for UNAIDS, the join co-sponsored program of the United Nations on HIV; it is the primary policy and programmatic secretariat for all of the Unite Nations agencies’ HIV programs.

Carlos Motta: Where were you born?

ES: I was born in upstate New York to a middle-class family. Most of my ancestors are dairy farmers and my father was a truck driver.

CM: And when were you born?

ES: I was born in 1954. I am 57 years old.

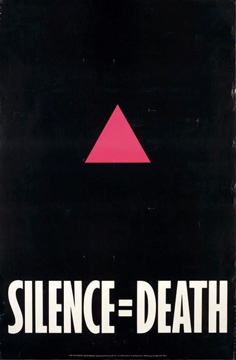

Silence = Death Project, Silence = Death, 1986

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: Do you identify as a gay man?

ES: I do identify as a gay man and I do self identify as a person living with HIV. I am one of the longest term survivors of HIV, having developed symptoms thirty years ago, in 1981 when the HIV virus had not been discovered and when the symptoms I was experiencing were called GRID (Gay Related Immune Deficiency).

CM: Can you tell me about having grown up upstate New York and how it was at the time to be gay?

ES: I was born in 1954 and went to grade school starting in 1960. I graduated from high school in 1972 so I grew up before the gay liberation movement was born. At that point homosexuals were a joke. There was one identified queer in our town who was and alcoholic, somebody that everybody made fun of, who hung around in one of the local bars, and often was on the sideline of sporting events. The joke was that he was there to look at the boys. I was a very sensitive kid and I cried easily. I had two older brothers who were major jocks. I was always really, thin, a bit uncoordinated, and was made fun of as being a “sissy.” I was very dramatic, liked movies, I was into band, chorus and drama and it wasn't until I became good in athletics, around the time when I was fifteen or sixteen and got bigger physically than everybody else that people stopped bullying me. I was then big enough to kick their asses.

CM: As you were growing up, were there any gay people, in popular culture or in other larger cultural fields that you identified with?

ES: No. There was hardly anybody out when I was growing up and that made it really hard. I always tried to have a girlfriend and I started having sexual experiences with guys and girls at the same time. As a really young kid in elementary school when I was playing doctor with the kids in the neighborhood, I was playing with both boys and girls and experimenting sexually with both. My older brother beat me up after catching me having sexual contact with another boy and told me that boys weren’t supposed to do that with other boys; he told me that if I didn't stop he was going to kick my ass. I then realized that maybe that attraction was not normal and I that should suppress it. Also because of all the bullying and having being called “sissy” and “little faggot,” I tried to suppress that part of my behavior.

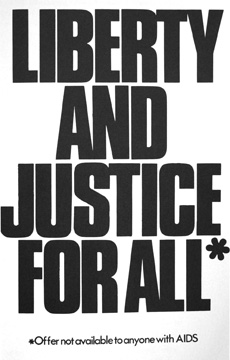

ACT UP demonstration at the General Post Office, NYC, April 15, 1987

Photo: Donna Binder. Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: And you suppressed it for how long?

ES: I had a girlfriend all through high school, but was never sexual with her. When I was a college freshman I got drunk and had sex with a guy in the college dorm the same week that I had finally scored with my girlfriend, it was so ironic. After that I continued to have sex primarily with my girlfriend, but also was occasionally getting drunk and having sex with a guy.

CM: What did you study and where did you go to school?

ES: I went to a state university in upstate New York and I studied psychology I think primarily to figure out why I was sexually interested in men. It wasn't actually until I was a senior and had taken a couple of courses in alternative sexual development, sexual deviancy, and adolescent sexual behavior that I was exposed to a group of gay activists from New York City who came to the university at the invitation of the psychology professor. They talked about a gay lifestyle as an alternative lifestyle and not as an illness as it was still classified in the American Psychological Association’s list of diseases. This was the first time I started to think that maybe it was actually okay to be attracted to other men. I thought I may be bisexual and that I should go to a graduate school where there was a gay and lesbian association, where I could get exposure to people who didn't runaway the day after a gay sexual experience. My experience so far had been with guys that said: “Oh my god we were so drunk last night, we can never do that again, don’t tell anybody what we did and I don’t want to ever do that again, so don’t try it.”

I went to the University of Colorado in Boulder. There was a gay liberation organization there and Allen Ginsberg was a teacher at the Naropa Institute, which was a Buddhist institute in Boulder and helped organize a gay and lesbian association on campus.

Gran Fury, Art is Not Enough, 1988

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: In graduate school you were also studying psychology?

ES: No, I studied public administration. I had decided my senior year that while psychology was interesting, I didn't want to be a teacher or a psychotherapist, and that I would rather have a career in business.

CM: When did you move to New York City and what did you do here when you first came?

ES: I moved to New York City in 1980, and when I moved here I got a job working for American Standard, a plumbing supply products corporation. Eventually I went to work for Citibank in human resources and then worked for a Human Resources consulting firm prior to being forced onto long-term disability with an AIDS diagnosis.

CM: What kind of gay community did you plug into when you moved to New York?

ES: When I moved to New York I got into the gay scene fairly quickly. I met people like Larry Kramer who had written a book called “Faggots.” He was certainly one of the most vocal and prominent gay people in town. I kind of fell into his crowd and I started very quickly going to Fire Island and became part of the gay the professional circuit.

CM: When did you become aware of the presence of HIV/AIDS in New York?

ES: I became aware of it really early because of my friendship with Larry Kramer. He started organizing something that called Network, which was a group of gay and lesbian activists who were leaders of the gay liberation movement. Some physicians like Larry Mass and people like Michael Callen, Peter Russo, and others began meeting on a regular basis to share information about this new illness GRID that was cropping up in the community. I went to that group for a while in 1981-1982. I ended up buying a brownstone and started renovating it, so I fell out of that group before it became Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC).

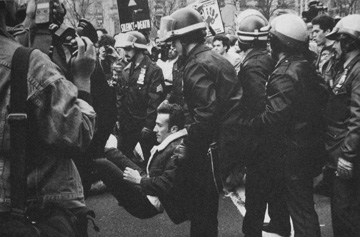

Police arrest an ACT UP member for civil disobedience at City Hall,

NYC, March 28, 1989. Photo by Tom McKitterick.

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: When did you get infected yourself?

ES: I think I was actually infected in a visit to New York City on New Year’s Eve of 1979, because I went back to Colorado on the first week of January 1980 and became really ill with flu like symptoms. I developed really bad swollen lymph nodes; they thought I had mono, and then they thought I had Hodgkin's lymphoma, but the blood work didn’t show up as either. I was really sick; I had really bad diarrhea and really swollen lymph nodes for a number of weeks until it finally subsided. Probably about a year later I came down with shingles and with some weird fungus infections in my armpits and groin. I was likely infected based on what my doctors and I can put together. That particular night I went to a place called Flamingo, which was a major club; it was kind of the center of gay dance world at that time. I was doing “white cross” that night, which was a form of methamphetamine. I was really high and went home with two other guys and we basically had sex for sixteen hours.

CM: When were you actually diagnosed?

ES: My boyfriend came down with Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) in 1984 and sometime after he was diagnosed our doctor got access to the early HIV antibody test and tested me under my boyfriend's, name because he already had and AIDS diagnosis, and I tested positive. It was either in 1984 or 1985. That was when the test was first available.

CM: You mentioned before that you went on disability from your job. Were you sick at the time?

ES: I wasn't really sick at the time, but in December 1991 my former employer forced onto long-term disability. I had already been in clinical trials for Zidovudine (AZT) and Didanosine (DDI).

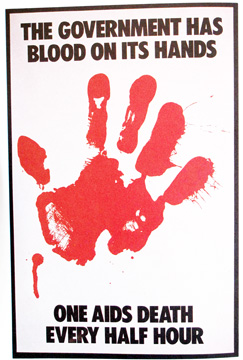

Gran Fury, The Government Has Blood on Its Hands, 1988

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: In 1991? Ten years later?

ES: Yes. My boyfriend had died and I had been on the “Phil Donahue Show” talking about how I had been discriminated against by my employer, because he had not given me time off from work to take care of him when he was sick. I mentioned he died on an airplane on the way to visit his mother with his secretary because my boss wouldn’t give me the time off from work to take him to see his mother for the last time.

There was a really contentious relationship between my former employer and me; he had tried to basically drive me out of the company. My boss found out from a colleague that I had been diagnosed as having full-blown AIDS and realized that my company’s long term disability program would pay for me to have health insurance and a portion of my salary for the rest of my life. They were in need of staff layoffs so they came to me and said: “Look, you have AIDS, you can qualify for long-term disability… You’re doing all this activism, you're not really that productive as an employee, everybody else in our unit is married, most of them have kids, a number of them are the only breadwinner and their family… You can go on long term disability and still get income and health insurance, so we want you to apply for it so we don’t have to lay somebody else off.” I said: “Well, I’m not sure that I'm ready to do that, I'm healthy enough to work.” They replied: “Well, here are your last six months worth of phone bills,” and they threw something on my desk, “Everything that is highlighted is calls you made to AIDS organizations or government employees as an AIDS activist, none of these people are your clients. Here are your billing sheets, your billable hours have depreciated forty percent since you became an activist, and based on these two things alone we have a reason to fire you. So, we can fire you, or you can apply for long-term disability, you choose…”

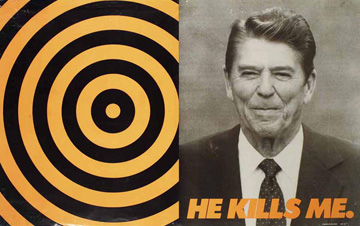

Donald Moffet, He Kills Me, 1987

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: When had you become an activist?

ES: That was in the end of 1991 and we had started ACT UP in March 1987.

My partner Scott died in July of 1986. Ironically his father also died of AIDS. He died in 1983 before Scott was diagnosed. He had had a triple bypass operation in Chicago in 1980 and came down with AIDS from a blood transfusion. He had a horrendous quick death. He was in a hospital in a Chicago suburb for several months that was really AIDS-phobic. The nurses wouldn’t bathe him, shave him, or wash his hair. My partner was literally flying home on weekends to take care of him. He would come back talking about how the feeding and oxygen tubes had flem crusted all over because nobody was cleaning them. He had to go insist that they change the tubes because nobody would; not even his own mother-in-law, who was afraid to touch her own husband because of AIDS-phobia. Scott was really insistent that he himself never be hospitalized. Even though he had pneumonia for several months, his physician, who was a personal friend, always came to the house to hang the IV bags.

When I learned there were many homeless people with AIDS and having known how Scott insisted on being cared for at home, I decided that I would use my housing renovation skills to try to develop AIDS housing. I called Larry Kramer and told him: “Hey Larry, Scott died. You know I've been doing renovations for buildings in Harlem and I would like to try to get in touch with other people who are trying to provide housing for homeless people with AIDS, because there's lots of buildings in my neighborhood and I know how to renovate buildings. So I’d like to develop some AIDs housing.” And he said: “Oh that’s a great idea you should talk to Doug Doran, or to the AIDS Resources Center, but I'm giving a speech at the Gay and Lesbian Community Center in two weeks where I’m actually going to call for a civil disobedience organization to be founded to do some anti war type protests to try to get the government to do more research to find a cure for AIDS, and to try to get a more appropriate societal response. Would you come to the speech and be a plan in the audience and when I call for volunteers stand up and be one of the people that offers to help and you give any suggestions you can on how we can organize the first demos?” I agreed to do that, I was at the first speech, and I was one of the first people who stood up. I was young and better looking at the time and had a very pretty boyfriend, so the two of us became some of the early “poster children” of AIDS activists because we were both out about our HIV status, about being gay and we were very involved.

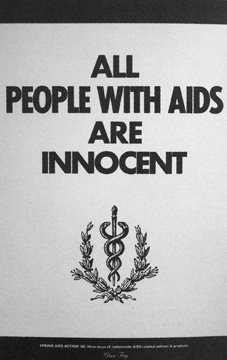

Gran Fury, All People Are Innocent, 1988

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: Can you explain to me the foundational motives or ideology of ACT UP?

ES: ACT UP took many of its own development queues for the early gay and lesbian liberation and the anti-war movements. We decided really early on that we were going to use “Robert’s Rule of Order”; that we were going to be an equalitarian organization where everybody’s voice

had equal weight and that we were going to do a majority rule voting process to determine what we would do. We decided that members of our group would facilitate discussions, that anyone could present ideas, and that we wanted to do “in your face” street theatre type demonstrations that would be non violent in nature, but that would draw public attention to our issues.

There were lots of people that were writers, actors, and worked in entertainment in one way or the other, so we quickly learned that street theater and sexy images, graphics and gimmicks were really effective at drawing media attention. We quickly learned that the media was really lazy, and stupid, and never properly represented the images or the issues that we were trying to draw attention to in their articles. We learned that if we had posters and graphics that clearly spelled out the intent of the demonstration and our demands, the message would get conveyed to the public.

We started using the sexy graphics and posters like some of these that are reflected in this book (At this point Eric shows images from “AIDS Demographics” by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston” to the camera), so that we made the messages we were trying to get to the public very clear. We used controversial images, like erect penises and clean needles and we did things like “kiss-ins” in the middle of the street to draw attention to how homophobia was undermining the epidemic. We said things like: “ALL PEOPLE WITH HIV ARE INNOCENT,” in response to the priorities of early programs that only wanted to help the poor children whose mothers transmitted the virus to them, and not the homos or the junkies who deserved to get to HIV.

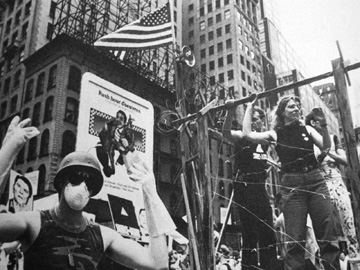

ACT UP "quarantine camp" in the gay pride march, NYC, June 28, 1987

Photo: Donna Binder. Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

We were drawing attention to governmental leaders who were shirking their responsibilities. Ronald Reagan never said the word “AIDS” or talked about HIV for the first seven years of his presidency, so we basically called him a murderer. We did things like constructing a concentration camp on the back of a float-bed truck for gay pride parade in 1987; the first ACT UP presence in New York City’s gay pride demonstration. We literally, me with my power tools and some friends, constructed a tower on the flatbed of a pickup truck using two-by-fours for a fence post and barbed wire and mesh to make a concentration camp on the back of the truck with a rifle tower up by the cab. I sat on the roof in a suit with a Ronald Reagan mask on and wearing yellow rubber gloves, laughing and pointing at the AIDS victims that were dressed in back, while people in police and military uniforms with masks and rubber gloves walked around the perimeter of the concentration camp. The banner on the side of the float said “Test Drugs, Not People.”

Police arrest AIDS activists at the White House, Eashington D.C, June 1, 1987

Photo: Jane Rosett. Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: Were you severely policed by the authorities?

ES: Our early demonstrations were. Look at this image of the police wearing big rubber gloves. It was the first demonstration we had at the White House, where a number of leaders of AIDS and gay and lesbian organizations, and some political officials pre-scripted a “die-in” in front of the White House where they would be arrested to drop more media attention to the fact that people were going to jail over the lack of a governmental AIDS response. The police showed up with rubber gloves, not medical rubber gloves, but orange rubber gloves that you would use to clean your toilet, and painting respirators, because they were touching people who may have HIV and they didn’t want to get AIDS from them. My flamboyant boyfriend started laughing like hell when he saw the yellow rubber gloves on these cops and started yelling: “Your gloves don’t match your shoes, you’ll see it in the news!” It actually became the chant for anytime that we did a demonstration where the police showed up in riot gear.

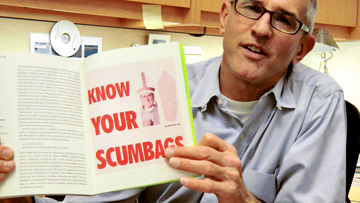

This is one of my favorite images from the AIDS epidemic. It was when ACT UP invaded Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. Archbishop John O'Connor is wearing a hat that looks an awful lot like an unrolled condom. The ad says: “KNOW YOUR SUMBAGS. THIS ONE PREVENTS AIDS”. Cardinal O'Connor was blocking the distribution of safe sex information and condoms in New York City public high schools and we invaded his church because he needed to get out of the education system and stop killing people by denying them access to safe sex education and condoms.

Eric Sawyer showing Know Your Scumbags, 1989 by Richard Deagle and Victor Mendolia

Video still from this interview at Eric's office in UNAIDS

CM: How was the government responding to this growing civil movement? Were you ever addressed directly?

ES: What ended up happening is that we had kind of a two-pronged approach to any kind of inaction. We learned really early on that it wasn't enough just to bring a list of demands and that we needed to frame entirely the issue we were addressing. We needed to provide background information about what the situation was, we needed to have a list of demands of the things we wanted corrected, and we needed to have some type of an action plan where corrective action could be taken to resolve the problem.

For example on homelessness and AIDS, the background information would be: “There are X number of homeless people in New York City, fifty six percent are testing HIV positive based on the percentage of tests in shelter medical programs. People with HIV are more susceptible for Tuberculosis because of the fact HIV kills CD for macrophages, which are the same blood cells that kill the tuberculosis germs, so people who have HIV are really susceptible to TB. More than sixty percent of people in New City Shelters test positive for Tuberculosis, therefore co-locating people with AIDS with people positive for TB is causing a Tuberculosis outbreak in the shelters that is over flooding the hospitals in New York. Therefore, we need medically appropriate housing to alleviate the Tuberculosis problems in New York City housing and the Tuberculosis problem in New York City shelters. Housing needs to be medically appropriate, have proper ventilation, have proper nutrition, allow people who are sick and weak to stay in the shelters or in the housing programs during the day and not be thrown out on the street at 7:00 AM, and not able to return to the shelters until 8:00PM,” which were the current programmatic guidelines for homeless people.

CM: How large had ACT UP grown to be at this point?

ES: ACT UP grew really quickly. Larry Kramer’s speech calling for the formation of ACT UP had less than a couple hundred people at it. Somewhere between twenty-four and thirty people showed up for three weeks to meetings at his apartment to organize the first demonstration. We had probably fewer than two hundred people at the first demonstration on Wall Street where there were a dozen pre-scripted arrests. The media went all over it because we publicized it. We had Joseph Papp who was the creative director of Shakespeare in the Park and the Public Theater build a life size puppet of Frank Young, who was the head of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and we hung him from a light post. We blocked Wall Street and did lots of media work ahead of time, so the news for days were reporting on this new gay group that was demonstrating about a better response for HIV. The next week our meetings went from the thirty people in Larry’s apartment to about three hundred people at the Gay and Lesbian Community Center and after the next couple of demonstrations we literally had eight hundred people showing up at our meetings. We had to move from Gay and Lesbian Community Center to the large meeting hall at Cooper Union. We had up to a thousand people show up for the demonstrations and ACT UP went from being just a New York chapter to over a hundred chapters in the U.S., and over two dozens chapters around the world in less than two years.

Gran Fury, Read My Lips (girls), 1988

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: Can you describe how these meetings functioned?

ES: We learned really quickly that we needed some kind of an operating procedure, so we organized a coordinating committee. First, a couple of members developed a working document that spelled out how the meetings would be run. I was one of the persons involved in that team. The primary drafter of that working document was a guy named Steven Webb who was a writer, but also an ex-hustler and Barry Gingell, who was a medical doctor with AIDS who was smuggling drugs from Mexico and Canada into the U.S.; drugs that were being tested by those governments as treatments for HIV and that were not being tested in this country.

The document was based on “Robert's Rules of Order” and talked about a process by which two facilitators, a man and a woman, would coordinate the meetings, how the agenda would be formulated and how the issues would be presented and voted on by the public. Emergency announcements would be done first, then there would be a discussion of actions that needed to happen to resolve a problem, and later there would be a report section that would report back on work of that was being done by the different committees.

Eventually there were so many committees meeting on issues such as scientific information, housing, women’s issues and pediatric AIDS for example, that we decided there needed to be a way to coordinate the work of these committees. We proposed to have a coordinating committee of elected representatives from each of the sub-committees that would meet on Sunday night before the ACT UP meeting on Monday to decide what the agenda would be for that week.

This grassroots model of running an organization became crafted into this working document that we started to send to cities and activists all over the U.S. and eventually the world to let them know how we were running our organization and how we were organizing our demonstrations. We developed an activist guide to a demonstration, model press releases, model fact sheets that had the overview, goals and objectives, the background information, the demands section, the action items, etc. We started coming up with tools to help other organizations form their own ACT UP chapters, but decided that we would not be a national organization. We wanted an administrative structure, we would share information and ideas, and would have conference calls with all the chapters to coordinate national actions, but each chapter would have to raise its own money, would do its own organizing, set its own priorities and develop its own committee structures. We formed this loose leaved collective that were local chapters based on a city as opposed to a state model. We would collaborate when possible, but would function independently and autonomously.

John Consigle, Demand Housing, 1989

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: At the same time that you are doing this work without ACT UP you co-founded Housing Works?

ES: The “Housing Committee” was one of the early committees that we established within ACT UP to focus on issues of housing. Initially I was trying to help a real estate developer and then work with the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, the Episcopal Diocese of New York and a couple other groups to develop housing, but it became clear early on that the faith based priorities and moral overtones of those organizations were interfering with condom distribution. They were trying to tell people with HIV not to have sex, not to bring people into the housing program to have sex here, that they wouldn’t distribute condoms, wouldn’t give women information about family planning, and that they didn't want HIV women to have an abortion if they were pregnant, etc.

We realized that we couldn’t get viable, effective and humanistic housing programs for people with HIV that we would want to live in ourselves, and that we couldn't get AIDS organizations to take on the added burden of trying to create housing. If anyone were going to develop a medically appropriate and humane housing it would be us. We decided to incorporate as a 501(c)3, raise our own money and start to develop our own AIDS housing. At the same time we organized the “Housing Committee” primarily to do advocacy and to combat inappropriate governmental or private housing initiatives.

CM: How did Housing Works work?

ES: The “Housing Committee” was formed to draw attention to ineffective programs and to advocate for medically appropriate housing. We got a wealthy donor to give us seed money, give us part of his wife’s office and let her secretary be our secretary. We hired our first employee, Charles King, who is still the president of Housing Works, to start raising grant money. We got development money from a model AIDS Housing Program that I put together from the New York State AIDS Institute that hired staff to develop the first AIDS housing model. We then applied for scattered site housing programs, grants from the City of New York for a program we helped develop, which was where an agency could hire social service staff to do the case management work in the drug treatment and referral to medical providers for homeless people with HIV and placed those homeless people in apartments that where rented just out of public housing stock. We got the city to agree to let us hire case workers, to give us the rent money to pay for those five apartments, and for us to coordinate the medical and social needs of those people that we were taking out of shelter system and putting into those apartments.

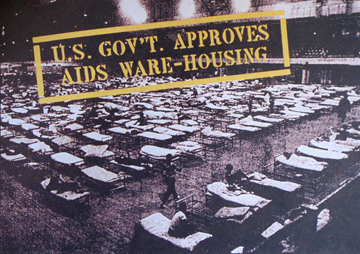

U.S. Gov't Approves AIDS Ware-Housing, 1989

ACT UP PWA Housing Committee.

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: As medical treatment became more accessible, and science started to develop, how did these two organizations start to change? That initial of urgency that developed into a social movement seems to have changed at some point. Can you give your thoughts on this?

ES: I think the demise of ACT UP, which went from having a thousand people coming to meetings in the late 1980s to three hundred people in the mid 1990s, began when the HIV “cocktail” was approved. That primarily happened for two reasons: Firstly, when effective treatments became available all of our friends stopped dying; it was no longer a “war siege,” where the community had to engage as if we were fighting a war. The fact that people were getting on treatments and their health was being restored, and that the number of deaths was dramatically reducing, ended the crisis siege. Many people who weren’t infected and who had careers, or whatever, went back to their normal lives.

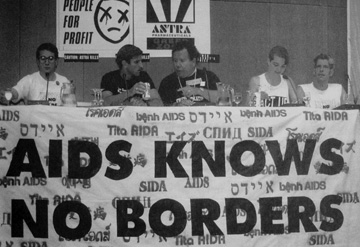

Secondly, when we succeeded in getting all kind of funding streams like the “Ryan White Care Act” and AIDS service organizations were formed, many activists got drained away from doing activism into full-time paid staff positions in these organizations. That dramatically dissipated the activist movement. The seeds of activism began to shift away from the United States or the developed world countries to focus on the developing world. We were getting access to treatment, programs and safety nets in the U.S., Canada, France, and Germany, etc. Countries with governments that were democratic and had adequate economies, provided aid to people with HIV. But the developing world had access to nothing, so the focus of activism changed. I was one of the first people that started organizing international things because I was getting invited to many conferences, global meetings of the United Nations, the World Health Organization, and other associations of nurses, and medical doctors, to speak about AIDS activism, about living with HIV and about housing issues. I started meeting many people living with HIV from developing countries who couldn’t even get aspirin and who couldn’t get the most basic treatment.

CM: Is that when you joined UNAIDS?

ES: No, that is actually when I helped to start something called the “Global AIDS Action Committee of ACT UP New York.” I eventually went on the board of The Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS and helped organize the first conference for people with HIV in in Cape Town, South Africa in 1995. I wasn’t invited to join UNAIDS until 2008, after having organized all the activist work outside and having put pressure on UNAIDS. I was invited to come in and help facilitate HIV communities input into the UN processes on HIV.

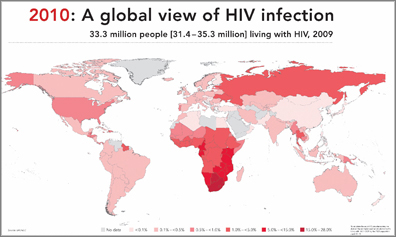

Source: http://www.unaids.org/documents/20101123_2010_HIV_Prevalence_Map_em.pdf

CM: Is there an HIV/AIDS crisis in the developing world at the moment?

ES: There is still a huge crisis in the developing world. We are making a certain level of progress on that crisis, but for example in 2006 there was a declaration of commitment signed at the UN by just under 200 countries, where they made commitments to reduce the number of new infections and the number of deaths by HIV every year. They made a commitment to get everyone access to HIV medications by December of 2010. We are in 2011 now, and while The

World Health Organization (WHO) and UNAIDS’ statistics say that around 15 million people need to be on HIV medications today, we have just over 5 million people on HIV treatment around the world. Only a third of people who need treatment today are on HIV medication. We have failed as a global society in obtaining the “Commitment to Universal Access.” There will be a meeting in June 2011, which is one of the things that I am working on now, where governments will negotiate a new commitment to delineate the global HIV response by governments for the next five or ten years.

CM: Is HIV/AIDS activism today primarily professionalized, or are there in any of the developing countries movements that could be compared to ACT UP?

ES: There still is a lot of activism happening at a grassroots level by non-professionals. Many networks of people living with HIV are still doing, not only the majority of activism and advocacy around HIV, but they are also still providing a major portion of the care, support and services for people living with HIV.

There are some global and national networks and local organizations of professionals that do more advocacy as opposed to activism, but keep in mind that one of the last things to be provided funding for is activism and advocacy. People will give money to case workers, to doctors, to nurses, they will give money to take care of orphans, but they don't view activism or advocacy as something that should be paid. Activism holds governments accountable, so why would a government pay for people to criticize it? Activism is suffering dramatically around the world. Grassroots groups of people living with HIV that are doing a lot of the educational work, and are providing care and support for people living with HIV and their extended families, are, if not totally, dramatically underfunded. These organizations that are doing a lion's share of the work are not getting the adequate level of financing and support that they need to do their jobs.

Eric Sawyer (second to left) at the 1992 Int. Conference on AIDS, Amsterdam

Source: "From ACT UP to WTO" edited by Eric Rofes

CM: What do you think the younger generation of queer Americans in this country has learned from the legacy of ACT UP? How is AIDS perceived today in the midst of it being a controllable disease? Is there a sense of urgency today?

ES: There has been a huge generational divide between queer youth and my generation or the generation that immediately followed me. Most young people today, including queer people and queer activists, grew up after the HIV virus was discovered, and after the HIV epidemic was widely known. Most of them became teenagers and young adults after the AIDS cocktail came to the market so now we are in 2011, and many of them think of HIV as a chronic illness that you can take medication for and live a healthy live. They don't see AIDS as a crisis. They don't have a sense of urgency, they don't fear HIV and so they are not that concerned about getting HIV, they engage in unsafe behavior, they are unwisely and unacceptably exposing themselves to risk of HIV infection and many of them are getting HIV.

Pharmaceutical companies present ads and commercials of men climbing a mountain or running a marathon while they are taking this latest approved HIV medication. People think that one pill is going to allow them to run marathons and climb mountains, not knowing that there are horrendous side effects, that drugs don't work for everybody, that people are developing neuropathy, diabetes, liver and kidney problems, wasting syndromes, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, and a whole laundry list of side effects that are debilitating and often kill people far earlier than someone would die if they weren’t HIV infected and getting these complications that are caused by the drug’s side effects.

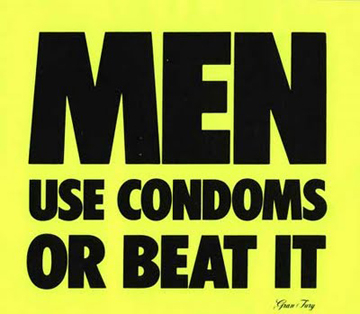

Gran Fury, Men Use Condoms or Beat It, 1988

Source: "AIDS Demographics" by Douglas Crimp with Adam Rolston

CM: Are these some of these issues that ACT UP is working on today?

ES: These are definitely some of the issues that ACT UP is working on and we are trying to reengage young people around the need for condom use, safer sex practices, safer needle use, and harm reduction techniques. We encouraging people not get infected with HIV and it is difficult. There is also huge ageism amongst the queer community. When you are young, pretty, have a great body, can go out and party all night, are cool and hip, everybody wants to you know, but if are a bit older, if you have gray hair, don’t have a gym body, don't party all night, who the fuck wants to talk to you? There isn’t much mentoring happening and there isn’t much cross-generational dialogue between gay youth and older gays and lesbians.

CM: What are your thoughts the subculture of bare backing and how it promoted by pornography? How do you do you think that it becomes such a strong industry?

ES: I think it has become desirable because it is new and dangerous. It is exciting because it is something you are not supposed to be doing. There was a time period when pornographers felt a sense of responsibility to ensure that all of their actors engaged in safe sex and they made big deal on showing people putting on condoms. There was an effort to try to eroticize condom use. Then a few people started saying: “Well fuck that, it’s really hot to take a load of cum up your ass,” and started doing bare backing videos, and then it was like: “Oh, my god did you see that? Oh, my god that’s so hot!” So it became edgy and in vogue to say: “Oh fuck it, don’t tell us how to fuck.” Bare backing porno became cool and it is really awful because it is encouraging many people to take risks that they are eventually going to really regret.

Weblinks:

ACT UP NEW YORK

HEALTH GAP

HOUSING WORKS

UNAIDS

↑Top