People call Against Equality utopist. But why be anything less? Why set low goals or limit your vision? Utopia is not a place we are going to get to; it is a process, a way of envisioning a future. It is important not to lose that. People want to be pragmatic and identify marriage as the winnable thing, but this seems ideologically ridiculous to me. Why would you compromise a vision of the world you want to live in for crumbs from a table you don’t want to sit at? I get frustrated with this concept of gay pragmatism, like we just have to be pragmatic, and invest in incremental change. Incremental change towards what? A world that sucks? A world that is totally classist and racist, and hetero-supremacist? I’m not working towards that.

Ryan Conrad

Download interview in PDF format ![]()

An Interview with Ryan Conrad

February 11, 2011

Carlos Motta’s studio in New York City

Ryan Conrad: My name is Ryan Conrad. I am from a small town in central Maine where I have lived for the last ten years. I have been part of a queer youth organization called Outright Lewiston/Auburn (Outright L/A), an LGBTQ youth drop-in center that is open once a week. We also do outreach programs training service providers like teachers and healthcare practitioners to create safe and affirming environments for queer and trans youth. Much of the work I do involves directly working with queer and trans youth, mostly kids living in poverty in small towns and Catholic environments.

I am also the founding member of Against Equality, an online publishing, arts collective and archive doing work to challenge the idea that queer and trans people need to be included in heteronormative institutions and systems like marriage, and the push to overturn the military “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” law, as well as the problematic hate crime legislation, which signals a never-ending always-extending prison industrial complex we think disproportionally effects queer and trans people. I am fighting the demand for inclusion in those systems and institutions. I have also been working as an independent artist and ad-hoc scholar the last three or four years since finishing grad school. Most of my work exists outside of a strictly arts context, if there is an outside of that.

I live in a queer collective house in my town in Maine, which has been a project for about six years. It has become a queer beacon safe house space where we hold social events and have film showings, dance parties, and some lecture style stuff, but primarily cultural and social queer events in a town that doesn’t have a queer meeting point, where there is no gay bar. That is sort of the broad walk of things I have been involved in.

Ryan Conrad, Pierre Seel (Home page image of Ryan's website)

faggotz.org

Carlos Motta: How did you choose the name for Against Equality, which is a very incendiary name when it comes to LGBT politics in this country? Equality has been constructed as the pillar of gay politics in America.

RC: The Against Equality project grooved from an original project that was very personal and geo-specific to me in relation to a blog I started around 2009 when the gay marriage referendum went to vote in Maine. I was really pissed off and angry about how the campaign was being run, and the zapping of resources from all other queer or trans things in this state. All money, energy, and volunteer hours were consumed by this single-issue campaign that I didn’t see as solving the problems people imagined it would. For example, people made marriage a solution for health care issues because married couples can share health insurance but there is an important distinction to make between health insurance and healthcare. People were talking about sharing health insurance after marriage without addressing the reality that working class people, like me, don’t have health insurance through their work. If I got married to either of my lovers I still wouldn’t have health insurance because they don’t. This was sort of like a sham being sold to poor people all across the state, particularly poor queer and trans people, as if marriage was going to help them in some way. I didn’t believe it.

The campaign in Maine was specifically run by Equality Maine, which identifies itself as the gay and lesbian activist organization, but they only organize around gay marriage. They don’t actually do anything else and they have a huge budget: It is a non-profit industrial complex. I started the blog and wrote an essay called Against Equality in Maine and Everywhere, which showed the material effects of the gay marriage campaign in Maine, where funding comes from, where resources were allocated and how money was spent. I included a document from a statewide symposium hosted by the Maine Equality Fund in 2008, which listed LGBTQ-identified priorities of what we should be working on as a community for the next ten years. Marriage was mentioned only twice in the Executive Summary of this two-day symposium. It is first mentioned as part of a comprehensive set of family law changes we should be pushing towards, and then mentioned by the Queer Youth Caucus that voices being tired of how much space gay marriage takes up in Maine’s gay political arena. It is interesting that queer youth voices were totally ignored. In this entire document, created by people from all across the state, LGBTQ marriage is one bullet point under one section over two pages of Executive Summary, yet it is getting millions of dollars. That was really frustrating to me.

Ryan Conrad, Future of the Past: Reviving the Queer Archives (2009)

Another document referenced in my essay was a poll published in the Family Affairs Newsletter created by queer and trans folks in the Bangor area about three hours north of where I live. Their poll showed something like 63% of respondents saying gay marriage is not a priority and something like 33% said it was their last priority as an issue the state needed to work on in a gay and trans context. Overall I felt like the community was being ignored while professional activists, working for professional gay and lesbian organizations that were getting funding from different sources and were conforming to the national agenda. That really pissed me off.

The campaign was also run so poorly, with a goal of mobilizing the vote along the coast where there are liberals and money while abandoning the rest of the state, like where I live. It basically created an opportunity for all this homophobic fervor to be out in the open with no one to challenge it, except in places where it didn’t need to be challenged as drastically as it did where I live. It was super frustrating to feel that people in Portland, Maine were stirring up a bunch of shit but I had to be the one dealing with the queer and trans kids coming to our drop-in center, feeling totally destroyed after the referendum failed. The people actually doing the work had to pick up all the pieces as opposed to these high-paid professional class gay and lesbians that live elsewhere and have access to a greater level of acceptance and services. Thinking about the rest of Maine, there is nothing for queer and trans people, and there is a massive platform for homophobia, on radio, TV, and in print. There is all this homophobic anti-queer stuff coming out and there is no one to push back against it in the more rural communities. Gay marriage was basically an urban-centric campaign that totally abandoned queer people all across the state by stirring up all this shit and then not actually being around to knock on doors and have community dialog about the issue.

Against Equality started with that essay and I am making a lot of noise because I don’t think Maine is exemplar. This model is used all over the place like in Maryland, Rhode Island, Washington State and Oregon State. I know they are next on the national agenda because the strategy is for blocks of states to approve gay marriage and then have those blocks of states pressure the federal government to push it on a federal level. It is a chess game, and Maine was used as a pawn in a larger national agenda for gay marriage while ignoring the actual local needs within states.

Ryan Conrad, Gay Marriage Will Cure Aids (2009)

CM: Can you explain politically why you think gay and lesbian organizations have been fixating on the issue of gay marriage as opposed to addressing other social needs?

RC: I think the professionalization of gay and lesbian activist organizations has a lot to do with it. Within the non-profit sector you answer to your funders and do what your funders want you to do: A hierarchy of people with money still get to decide what happens. Equality Maine is a perfect example of this. They hosted a series of community dialogues and I actually went to one thinking: “Ugh, it’s Equality Maine, I’m not going to agree with anything they have to say.” I gave them the benefit of the doubt because it was a community dialogue right? Wrong. It was a presentation on how they were going to win gay marriage. They didn’t ask any questions, they had charts showing their strategies and their next steps if gay marriage passed in the referendum. This isn’t a community dialogue. I kept thinking: “How did we get here? We didn’t ask questions yet?” This comes from super professionalized organizing, like the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF), which gives you a $100,000 to work on gay marriage. Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders (GLAD) based in Boston, applied for grants from Maine Community Foundations Equity Fund to do gay marriage advocacy in Maine. So, people from Boston were coming to Maine and instead of listening and asking people what they wanted, out-of-state organizations began to zap local resources to do what they wanted. That is what continues to happen. I think it is because of the non-profit industrial complex, where career activists answer to a group of upper class gay funders that want to consolidate power privilege and property through this thing we call marriage.

CM: It seems like you are underlying a class critique of the way politics are being built?

RC: That is hugely what Against Equality is about for us: A materialist class critique to actually talk about marriage, to wipe away this gloss of affect that portrays marriage as being about love and family, when it is actually a social contract between two people and the state and the transfers of property, power and money between them. I think it is really hard for people to step back from this sheen that has been put over marriage. Gay and lesbian activists have been digging up this rhetoric of affect and love, questioning how love can be outlawed, and it is actually not what everyone is talking about but a distraction from actually talking about how sexual identity decides whether people live or die, have access to healthcare or not, can move across boarders, and access jobs. People aren’t talking about that piece. The class critique is huge for me and comes from an urban/rural critique as well. Not to suggest that there aren’t poor people in urban settings, but in Maine in particular rural equals poverty. For me there is always a critique of urban gays with more money than the rest of us setting the agenda while people outside of major urban centers don’t have access to any resources and are most at risk for poverty and HIV. It is pretty ridiculous how urban-centric the conversation has become, something which is part of the class critique as well.

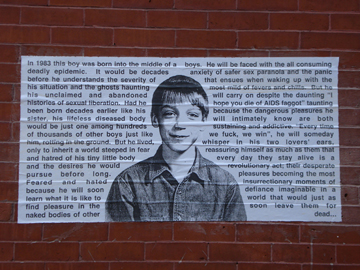

Ryan Conrad, b.1983 (2008-2009)

CM: Needs are different in different places but what needs are you referencing when you speak about “real” needs?

RC: It is totally geo-specific, and also different for different parts of the community. We can’t talk about the gay and lesbian community or the queer and trans community as a single monolithic thing right? The idea that it is a community is also problematic, suggesting, based on sexual identity characteristics, that we all have things in common, when really we have multiple identities and intersubjectivities. We are not just queer but we also have a class, a race, an ethnicity, an ability, a citizenship status and so on, making it complicated to define the needs. I am more hesitant to say what the needs are than to talk about what the processes should look like to get to those needs; processes like the Maine Community Foundations Equity Fund symposium, where people were brought from all over the state for two days to actually hash out the priorities of our communities. I think that document is super valuable in Maine and I hope other places are doing similar things where community organizations can get funding to host a free conference, provide sliding scale housing and travel reimbursement to get people from all over the state to have these conversations, so that it is not just people with resources and money who are able to take time off from work, travel and pay for a hotel who are determining our priorities.

Specifically on marriage: More than saying marriage shouldn’t be a priority, we need to also ask what does marriage do? To me, it fulfills a material need; marriage can give you access to healthcare, or can permit you to move across boarders in certain circumstances. Let’s determine these material benefits of marriage and then figure out how everyone can access those things without being compelled to marry. Everyone should be able to access healthcare. The other piece is affect: what are our communities’ affective needs and what does marriage do for them? It suggests our relationships are valid when the state condones our love. The desire for that is something that needs to be reckoned with, we can’t write it off as it stems from a long history of homophobia, transphobia and violence against queer and trans people. Seeking out validation and respect from the world as to our relationships and our humanity is important. I don’t think marriage is the way to do that obviously, but paying attention to the affective and material needs of our community and figuring out ways to meet these needs without surrendering ourselves to the Church and the State is the question for me. We need community dialogue about addressing questions of affective and material needs.

Against Equality logo (2009-2010)

CM: Does Against Equality play a role outside a discursive critique in the field of activism? In other words, are you thinking of ways of implementing political strategy and perhaps virally influencing the way organizations are running their agendas?

RC: I feel we are too disorganized at this point. There has been talk of setting up conference call lines because we are spread out. I live in a small town Maine, the co-editor of the book lives in Chicago, contributing members live across the United States and Canada, so it is kind of a rag-tag group of people who do many things. It is important to remember Against Equality isn’t really an organization. We primarily exist as an archive, though archives have political potential and impact. I made my primary commitments to Outright L/A because that is the direct material thing in my community where I feel I have a big impact. Against Equality is an extra thing that a bunch of us do on the side as opposed to being the primary organization where we are going to have a phone tree, structure, and whatever. It has been pretty ad-hoc. We have been talking about changing that slightly to do bigger projects that impact more people, but in terms of how we influence, say the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, or the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), our impact occurs in terms of getting people to divest from those organizations. For example, our logo is the greater than sign in yellow with a blue background which is a spinoff of the HRC’s logo of an equal sign in the same colors. We like to play with semiotics and re-appropriating symbols. Our recent “Just Say No to Marriage” slogan was a spinoff of Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No to Drugs.” Her image is actually trademarked so I don’t know if we will get in trouble. I see our role as more cultural than political in trying to create space for these conversations and we are skeptical of the structures of non-profit political action groups. We don’t think it is wrong for people to get paid, it is really important to value people’s labor and work, but many non-profits get co-opted because of funding and the role of board members that are professional and career activists. That is not a direction we are interested in going. This structure makes us quite fluid and quick to react to things and gives us more autonomy.

CM: Are there historical entities in the United States that influenced the way you are operating as a collective and the type of work you are producing?

RC: Yeah. Some contributors to the project are also part of Gay Shame in San Francisco, which also functions pretty ad-hoc, with open meetings but a collective structure where people bring what they want to the table and the group works toward consensus. Also, LAGAI-Queer Insurrection, based in the Bay Area, has been around since the early 1980s publishing the newsletter Ultra Violet and we have published our work in it. They are super friendly with us, so we are building both personal and activist relationships. My collaborator Yasmin Nair in Chicago is working with Gender JUST and Queer to the Left, so I feel like we all have different groups we are in dialogue with, but it is not necessarily an official relationship or coalition but we are friends or we have worked together on projects.

Ryan Conrad, Radical Queers Historical Figures Trading Cards (2009-2010)

CM: The critique you are articulating was much more present in the wake of the sexual liberation movement. Today it seems more of a minority position and is perhaps even frowned upon by most LGB people. From your perspective, what are some of the causes of this normalization within LGB communities in the last thirty years?

RC: Act Up (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) has a sort of funny, dark, sad component to it that people never talk about. Act Up used to push universal healthcare as the norm. There were protests all the time for universal healthcare but as the group was fizzling out in the mid to late 1990s there were Act Up chapters aggressively pushing a gay marriage agenda. Act Up did many amazing things, but it wasn’t perfect. I think there has been a cultural conservative shift that came from both the right wing backlash in the 1980s and 1990s and from many deaths.

It is hard for me to know this because I didn’t live it. I am 27 so I am inheriting this history and I have had very few older queer mentors. I actually had to work really hard to meet older queers that were involved in Act Up or any of the more radical organizations that had a similar ideological stance to Against Equality. It has been difficult to find those people and especially being from a small town, not New York City or San Francisco, it is difficult, and I think that is huge. You can’t take a queer history class in high school, you can barely take one in a college or university. Not to have a historical context is huge. Queers have to teach themselves all their own history, which is a lot of hard work. Maybe it is easier with the Internet in places where most people have access to it like in the United States. Still, there is a huge gap in knowing our own histories. It is scary because I think about the kids in my program at Outright L/A who know nothing but the gay marriage agenda that has dominated political discourse for ten years, as if that was what gay liberation was or all it could be. That scares the hell out of me and motivates my work with Outright L/A. I can be like one of those older mentors, talking about Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera and Jean Genet, I can share those stories and point them to books and videos and cultural examples for this other way of organizing your life and approaching the political landscape. It is important to ask why this historical amnesia or gap exists. Here we need to think about the prison industrial complex and the criminalization of intergenerational queer relationships particularly between men. Queer men are constantly fearful of being labeled pedophiles or sexual predators and this cuts off the possibilities for intergenerational relationships even when they are non-sexual. The prison industrial complex, which hate-crime legislations would currently expand, creates a vicious circle that contributes to this void in our history. There is the criminalization of intergenerational relationships and there is the reality of thousands of dead people who can’t speak for themselves.

CM: I understand one of the Against Equality books you are going to publish is on hate-crime legislation. What is the work that you are doing regarding that?

RC: I feel like this is the most complicated piece. People are like: “Fuck the military, fuck marriage, we are anti-assimilation,” but when we talk about hate-crime legislation and protections, it doesn’t seem right. For us, the prison industrial complex doesn’t solve problems; it compounds them and makes them worse. Is putting people in prison actually challenging or fixing the harm happening in and against our communities? Prison is not The Department of Justice, it is The Department of Corrections, so this isn’t about justice, it is about locking people up without rehabilitation: It is penalization. Maybe investing in the prison industrial complex as a means to protect our community isn’t a great idea for actually solving problems. It is also important to remember how surveillance and policing function disproportionally in queer and trans communities presently and historically.

Ryan Conrad, To the Barricades! (2007-2009)

CM: Can you explain that a bit more in depth?

RC: For example, Trans-people particularly have more difficulties with employment so sex work becomes a means for being able to meet basic material needs. Trans sex workers have been profiled, so even if you are not a trans sex worker, but you are a trans person walking down the street, you can be arrested for solicitation, so there is this criminalization and policing of queer and trans communities, particularly of trans people of color who are disproportionally being placed in prison. Folks in Gay Shame have been working on this. There are also new prisons, in the United States and Canada; what they call “gender-responsive” prisons where non-gender-conforming people are taught how to appropriately act their gender, prisons that would have manners for women instruction as part of their rehabilitation. All of these things contribute to our critique of hate-crime legislation as a thing that doesn’t solve our problem but aligns us with an institution that actually criminalizes broad segments of our community.

CM: With the critique you pose on gay marriage and hate-crime legislation, you seem interested in a complicated systemic change that requires looking at how this country has institutionally framed these debates.

RC: This comes back to the name Against Equality. We are actually suggesting the idea of equality in the status quo and the systems and institutions that already exist were designed for a hetero-supremacist society that is classist and racist. Maybe we should be investing our energy into transformative ways of meeting our material and affective needs, dealing with harm and violence in our community and addressing whatever the ideas of nationhood and national security are.

When we talk about equality, we are talking about this idea that we need to have equal stake in these hugely problematic, and I would say, deadly institutions. We are against that. Some people at events we have done say we are not against equality but for real equality, or against this sham of equality. I guess if that is how you need to frame it for yourself to get what we are saying, then that is right, we are for radical equity. We are talking about economic justice and social justice on a broad scale and not just single-issue identity politics that none of us feel invested in.

CM: It seems a fairly impossible project to accomplish in this country doesn’t it?

RC: Yeah, people call us utopist. But why be anything less? Why set low goals or limit your vision? Utopia is not a place we are going to get to; it is a process, a way of envisioning a future. It is important not to lose that. People want to be pragmatic and identify marriage as the winnable thing, but this seems ideologically ridiculous to me. Why would you compromise a vision of the world you want to live in for crumbs from a table you don’t want to sit at? I get frustrated with this concept of gay pragmatism, like we just have to be pragmatic, and invest in incremental change. Incremental change towards what? A world that sucks? A world that is totally classist and racist, and hetero-supremacist? I’m not working towards that.

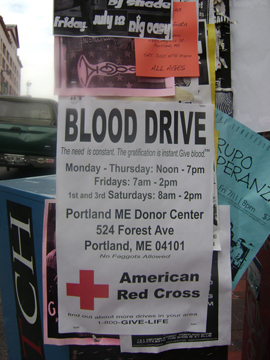

Ryan Conrad, No Faggots Allowed (2008)

CM: The frame opened by a queer critique of systemic issues is incredibly important. Are you in communication with other marginalized groups such as immigrants, racial groups, and others that are dealing with similar issues from a different perspective? Is there some kind of camaraderie amongst these groups, or do layers of homophobia, which permeate many communities, continue to separate the work being done?

RC: Yes and no at the same time. It is important to remember that our community is multi-facetted and intersubjective. We aren’t just queer, but are queer immigrants and queer people of color, which isn’t to say experiences within people of color communities or immigrant communities are absent of homophobia, but to remember that while we may not be in coalition with specific organizations members of our community are part of those other communities. Something said at a Palestinian queer activist talk last night by a group called Naughty North, resonated with me: They encouraged creating a queer presence at radical activist events and a radical presence at queer activist events, so a queer presence at the immigration rallies and a pro-immigrant stance at the queer rally. I think that is sort of a normal operating procedure for most people associated with Against Equality; it is about everything through a queer lens.

CM: This reminds me of the 1970s in different context. The Marxist-Leninist or Marxist-Maoist movements and the sexual liberation movement were working together for the most part, until some socialists began claiming that homosexuality was a product of capitalism and there was a break between the organizations. I wonder how much of that kind of radical left, or conservative radical left legacy we carry on to the future.

RC: I wonder too about how the radical left in the United States doesn’t really exist or feels like it no longer exists.

Ryan Conrad, Negotiations (2009-2010)

CM: Maybe not in an organized way, but it does exist in microcosms.

RC: I feel like it has become so post-structuralist that the worlds where people inherit radical left American political history are about a post-gender and post-sexuality, which I find super problematic.

I agree binary gender is a social construction and we need to think instead of a spectrum where people aren’t one or the other, but somewhere on the spectrum, like no one is gay or straight, but all just sexual. That makes sense to me and I believe it, but at the same time it doesn’t acknowledge the material conditions such as being post-sexual but in a heterosexual relationship whereas I am not in a heterosexual relationship and that could get me killed. The Christian Right is not post-sexuality or post-gender so I feel there is some push back that needs to happen in left intellectual circles that perpetuate a beyond gender, beyond sexuality, or beyond marriage discourse. You can’t just be beyond it because you have to be against it at the same time.

I know it is a paradox to try and reconcile the need to fight this and actually be ideologically passed it. At the same time, you have to challenge it because the gay marriage movement is actually killing people. It is actually taking funding away from groups like Gender Just, which was recently denied grants because they weren’t working on gay marriage. There is a queer youth of color organization being told they will not be funded for work on demilitarizing schools and making them safer, and how can we be beyond that? We actually have to challenge this monster and be ideologically post this thing, which is a really hard thing for people to get, just like it is really hard for people to get that we are not against gay people getting married. I don’t care you know, but what is necessary to challenge and think about is this institution and how it works to mark somebody as worthy of living and others as not. You can’t just be beyond that. I am sort of referencing the Beyond Marriage Statement that came out in the early 2000s, it was a really important moment, but it is still problematic if we think about being beyond this thing that has huge material repercussions, including death.

CM: How have you collectively been thinking about “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and what is your position on the recent success of removing it?

RC: It is interesting that people are so wrapped up in it. Itis problematic because some people have this weird economic justice rhetoric, like this is going to help queer people in poor rural communities in the Midwest have access to job security. I think it is fucked up for someone’s job security to be dependent on whether they are part of the imperialist war machine that puts their lives and the lives of people of color all over the planet at risk. That is not economic justice: What planet are you people on? Queers for Economic Justice put out a great statement about how a military job is not economic justice, but a total farce and anyone who has convinced themselves that our military is designed to defend and protect the United States has bought a total lie, hook, line and sinker. The U.S. army is an imperialist army. Activist Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore was talking with Dan Choi on Democracy Now about how we could actually solve the social issues of poverty in small communities by taking a tenth of the war budget and putting it into social programming so people wouldn’t have to join in the military or live in poverty.

CM: How did Dan Choi respond, do you remember?

RC: I couldn’t follow his argument, but he was trying to make some moralist, humanist argument about how it is more meaningful when you have the choice rather than not having the choice, which to me was totally irrelevant.

Ryan Conrad, b. 1983 (video) (2009)

CM: It is interesting why so many of these issues are framed in the news around the kind of primacy of respecting an individual’s identity as opposed to a collective identity.

RC: Basically individual gay rights has trumped human rights on a global scale and I think people forget to step back and put it in a more global perspective. Now we have gay identity in the military, so your identity is honored as a military personnel but this doesn’t address the fact that human rights on a global scale don’t matter to the U.S. military. The global collective is thrown out the window for this hyper-American individualistic identity based on being able to express one’s sexual identity within the army: It’s American individualism against the world.

CM: Actually I wouldn’t call it American individualism because I don’t think it is specific to this country, I think it is specific to the way LGBT politics have been constructed in a kind of internationalist model, which may be spinning off from models in the United States.

RC: When I was in Cape Town, and Johannesburg in South Africa I could identify a Western European/American gay culture, which doesn’t make any sense there. It was the same bad music, clothes, hair and shoes. It was like I was in Chelsea but I was in Cape Town. I think you are right about this globalization of gay culture I think it is that type of individualistic rights-based gay and lesbian politics that is being replicated globally, but I also think there are interesting people contesting that sort of political landscape being transferred onto them.

With radical queer politics you can’t just transplant the ethic attitude, model and methodology to places that have an entirely different cultural context. You can’t just pick up something, like an idea of queer utopia, which has been honed in social, cultural, and political circles in New York and London and then just take it and plop it down in the Gaza Strip or Tel Aviv and expect it to translate because the social and cultural contexts are so different.

CM: One of the things that is interesting going back to the idea of this focus on the individual is how it feels that there is a kind of internalized homophobia when you think only of the individual because it is really about going back to the family structure and the idea of needing to be accepted within that family, and having to shape your life around the presets of the family nucleus, or the society, the school or the work.

RC: An example for me is the proliferation of the Gay Prom. When I was in high school we were like: “Fuck the Prom,” and all the queers, weirdos, and punks would go do something else totally fun. Now there are gay proms everywhere, with kids fighting about what couple gets to be king and king or queen and queen and I feel like there is a loss of the radical position where we don’t need to be included in this fucked up bullshit and can do our own thing.

I guess it comes back to that demand for inclusion, where we want our individuality recognized within the existent structure rather than asserting our difference and doing our own thing. Why seek affirmation from the thing you think is messed up in the first place? That shift has definitely happened since the late 1990s when I was in high school and it seems now it is a desperate push for affirmation and inclusion.

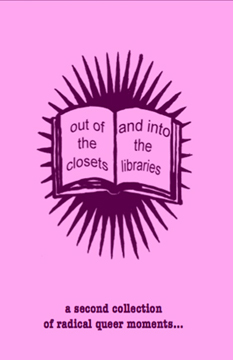

Ryan Conrad, Out of the Closet and into the Libraries! (zine) (2006-2009)

CM: It seems to me the last time collectivity was validated in this country, and not only in the queer world, but in general was with the AIDS crisis, because there was a real sense of urgency and threat of death. You are pointing to the urgency that is still here, but has been instrumentalized by a rhetoric that ignores a sense of collectivity. There is no sense of building a social movement and that is really terrifying.

RC: I think the only thing that seems like there is a cohesion and movement around is the gay marriage campaigns, which for some people resemble rallying cries, so it feels like there is a community building around it, but it is not real. It is money being poured in from certain groups of people to make certain other groups of people volunteer all night for a piece of pizza or something, that is the context of it. It feels like the queer left and the left in general don’t exist. Maybe part of it is fatigue. It is hard to be putting up a fight all the time. Yasmin and I have become the more public face of Against Equality and we started to get death threats from people after I gave a lecture in Georgetown.

CM: What kind of death threats?

RC: “I’ll chop you up into little pieces and throw you in the dumpster, you fucking faggot!”

CM: Coming from gay people?

RC: From other gay people, yes. Yasmin and I both received three or four death threats on Facebook as well.

CM: Well, you are messing with the most precious thing for gay people today.

RC: I know. They all just want to get married.

CM: I was actually thinking the most precious thing is Lady Gaga! Didn’t you say she was evil?

RC: Oh yeah, it totally came from the Lady Gaga thing for sure. She is an example of how people think about activism. You become a pop star and make a statement about something but don’t actually do the work, you just stand on the stage and become a puppet!

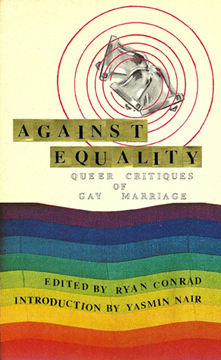

Against Equality, Against Equality, Queer Critiques of Gay Marriage (book) (2010)

CM: So, what is the path to this transformation that you are advocating for?

RC: That’s the question! Everyone wants to know what to do and what happens next. I don’t know what happens next. I don’t want that to be a cop-out, but if Against Equality as a collective defines the six-point strategy to gay utopia, we would be just as bad as Equality Maine, the Human Rights Campaign, or any of those other organizations that do the same thing. We actually are saying we shouldn’t be that, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have any ideas. I realize people actually need answers and to hear what you think, and then push back or work with your ideas.

CM: So what are you going to do?

RC: In terms of the collective I think our priority and our goal has been to create propaganda material around the idea of Neoliberalism and resist inclusion within the heteronormative or hetero-supremacist world. Create space to actually have these conversations has been our main objective and I think we have achieved that goal. It has been great. We have sold over 800 books in the last six months and we have been touring and lecturing. I am going to be on the West Coast for three weeks in April and all of this works toward opening up dialogue which feels really important. We are not just artists or academics creating or writing something and putting it out into the world, but actually doing events and having community dialogue.

CM: Artists and academics also do that! (Laughter)

RC: It is true, but it doesn’t always happen, right? You can just make something and put it out in the world and then walk away, so to actually go out and try to have discussions is doing some of that community building work of getting a bunch of people that are not sure about mainstream gay politics into a room and giving them historical context as to where we are coming from so they can put this information in their back pocket, like a bunch of ammo to continue conversations within their own communities and not only with like-minded people.

I think it has been really important to create that ground swell of people that are suspicious and can have those conversations in a geo-specific context and then figure out what the next steps are for them in their communities, whether it is to start other organizations, an art collective, do a video project, whatever. For me, it is coming back to my own community and figuring out, what I need to be doing here. I don’t know what the next steps are specifically, but for me, it is about working really hard to be a mentor to young people and making sure young people have access to queer history and hoping that builds another generation of activists and queer kids that are not necessarily going to jump on board with mainstream gay and lesbian identity politics. In terms of what a national or global movement looks like, I am not sure.

CM: Me neither.

RC: I think if anyone did know, I would be suspicious.

Weblinks: Ryan Conrad's website - Against Equality

↑Top