The horizon of the impossible is always shifting. At one point, it was impossible to think black people would be free in America. At another, it was impossible to see women voting. Thinking about politics as a system of impossibilities, where people control the imaginary of what is possible, I started to think through “Ecstatic Resistance” as a force against that. The “ecstatic” is about an encounter to me; is an encounter where you get turned on just enough that your boundaries shift for a minute. I am interested in work that brings you to this place and presents an alternate reality as a possibility, works that somehow physically affect you.

Emily Roysdon

Download interview in PDF format ![]()

An Interview with Emily Roysdon

April 15, 2011

Emily’s home in New York City

Emily Roysdon: My name is Emily Roysdon. I identify as an artist, writer, and organizer. I initially studied international politics, social movements and critical race studies at Hampshire College with Eqbal Ahmad. He was a very special man. It was only near the end of my studies, as I was discovering and developing a psychoanalytic vocabulary, that I began to study and make art. I was accepted to the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program so I came to New York, where I guess I fell in love for the first time in that special profound way. My girlfriend was in a band so I had one foot in the Whitney, in this critical studies program, and one foot in the punk, feminist pop world; two really good feet to have.

This is how everything started for me. I was wildly, radically repressed before coming to New York. I was born in Maryland and I have two moms. They are best friends and raised me along with my grandmother.

Emily Roysdon, Work, Why, Why not, live performance at Weld, Stockholm, August 1, 2008.

Courtesy of the artist

Carlos Motta: When you were growing up in Maryland, were you connected to a queer community?

ER: In college I knew queers, but, and I laugh about this now, I lived without acknowledging my feelings. I think this was because several of my best friends died when I was young and I blocked many things. I was not living with an emotional reality but instead made myself this strong intellectual life that lasted through college. At this point I was also functioning with this thing I called “the use value issue”; I thought I should be very useful. I should be a United Nations diplomat. Then I encountered Walid Raad and a few other important people like the feminist filmmaker Joan Braderman, so I had some inspiration for this last minute shift toward art I made at school.

CM: Can you describe the critical art scene at the Whitney ISP and the punk scene you discovered when you came to New York City and how they interacted with one another and began to shape and influence your artistic work?

ER: The feminist punk pop scene at that point for me was grounded in the band Le Tigre because I was dating JD Samson. With Le Tigre’s early records and touring I began becoming aware of the wide extended network of feminisms and collectivity. It was a really queer scene. I do not know what the demographics were, but I loved the Le Tigre audience. It was always so much fun to be on the floor with people. Le Tigre aimed at writing lyrics that validated and vindicated people while creating the most danceable music you can imagine. The energy was always profound. It was very real for people.

Le Tigre, This Island, Album cover, 2004

When I moved to New York for the Whitney ISP I met Sharon Hayes and Andrea Geyer, people who are friends of mine now. I had only made one art project at this point and was now accessing and encountering artists like Yvonne Rainer; really powerful role models.

CM: During this time, I lived on Suffolk Street right above Meow Mix and I saw Le Tigre perform many times. I associate this period with the parallel development of LTTR. What was LTTR and what has it become?

LTTR in conversation. Courtesy of Emily Roysdon

ER: LTTR was a feminist gender queer independent art journal. The project lasted six years and we published one thousand copies each year. We produced live performance events, radical read-ins, and all kinds of things that do not fit on the printed page. We started the project in order to materialize a valuable conversation we saw happening around us that we did not see getting played out anywhere else. We knew about Heresies and all of the creative projects of Act Up and did not think we were the first queer feminists to make a publication, but wanted to specifically create a venue for gender queer feminism, which had a wide net of allies.

CM: What was that conversation that wasn’t being enacted anywhere else?

ER: Our focus was on queer life and queer identity so in the early years of LTTR anyone who showed up was identifying and participating in the creation of that identity and lifestyle. At this point, there was not an external audience of people who wanted to watch or theorize queer academically. If you showed up you were part of the whole thing, and no matter what your body was like, or what you had done before, nobody took for granted what you would do or wanted to do that night. Everything was in play in quite new ways at that time.

CM: Can you speak about the influence of magazines such as Heresies and other publications produced in the 1970s? It seems like you are descendants of that tradition. Were you thinking about carrying on that legacy in any way?

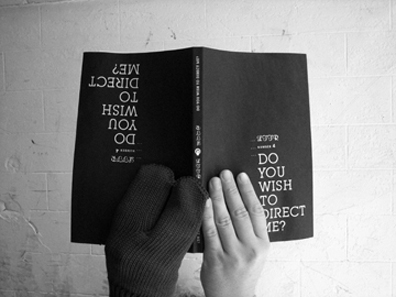

LTTR, Do You Wish To Direct Me?, Issue # 4, 2005. Courtesy of Emily Roysdon

ER: To be totally honest, when we started we were much more aware of the zines trajectory coming out of the punk scene. As we started to produce the journal, make decisions, and grow as artists we began taking those connections more seriously. We were always upfront about wanting to claim the history and support the artists who came before us as well as continue a legacy. That was always very important to us.

CM: Did you feel that legacy was neglected at that moment?

ER: It’s good that you say “at that moment” because we have seen some positive shifts in the last few years. Previously, nobody cared. If you saw the “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution” exhibit, which traveled to many places and made and incredible impact for many years, 99.9% of the work appeared courtesy of the artist. These artists still do not have galleries and are not placed in collections, but I think it is a little different now. We still are not being taught enough about women art makers and the feminist art movement, which is as a primary influence on everything we do now.

CM: The generation you and I have grown up in has seen a kind of normalization of gay and lesbian politics since the demise of ACT UP and into the Clinton administration. Do you think a political process of normalization is partially responsible for the neglect you are talking about?

ER: I can relate to what you are saying but I found the locust of my work and activity outside of this framework of normalization. Gays and lesbians were somehow normalized, even though not given many rights, we know trans people still aren’t covered under New York State discrimination laws, so that becomes the boundary of the periphery. I was less involved in the normalization: I was riding the train everyday with a gender queer person and it was still okay for people to come to them and say: “Are you a man or a woman?” or “You are so ugly!” So that was more what was affecting my experience.

LTTR # 4 launch at Printed Matter, 2005. Courtesy of Emily Roysdon

CM: You were seeing things from a margin in a sense?

ER: Yes. I think I will always make this choice in my life, as those boundaries shift, I will make sure to keep my eye on what the periphery is.

CM: I remember the first issue of LTTR, “Lesbians to the Rescue.” Can you speak about what you were rescuing?

ER: That is a funny story. When we did the issue, K8 Hardy and Ginger Brooks Takahashi wanted to do this thing and call it “Lesbians to the Rescue.” That was my first question too, rescue from what? When we decided the project would be a journal I think it was about a desire to take up the term lesbian in a heroic and performative way, rather than targeting something specific.

CM: When I interviewed Ellen Mortensson, a feminist theorist in Norway she spoke about a “hierarchy of oppression” within the queer community where at the top we find middle and upper class gay men, and then it cascades down to the bottom, where lesbians, according to her have remained invisible. Can you speak about your writing on invisibility in the zine?

ER: The text I published in the first issue of LTTR was titled, “Democracy and Invisibility and the Dramatic Arts.” It was the first I wrote in this style and I think it contributed to my identity as an artist and writer. It was an early act of defining my voice at the same I time I was defining a community, so being able to produce that text was crucial in many ways at that moment and had a lot to do with knowing who I was writing for.

At that point I used the term invisibility in a less straightforward way. I made a play on the idea of invisibility as being both a backstage space where we can get a lot of our power and a challenge of confronting more practical and real life situations where you need to be counted and cannot remain backstage. I took up this term because throughout this period I remained obsessed with issues and limits of representation because of my interest in social movements.

LTTR # 4 launch at Printed Matter, 2005. Courtesy of Emily Roysdon

As far as the hierarchy, last night a bunch of queer people and lesbians went into a gay bar and of course ended up getting a bit bashed for it, so this kind of misogyny still happens in the gay community. Conversations I have had over the years with groups of older feminists who can see changes in the ways my generation is living are really valuable. Once Jean Carlomusto said, as she was interviewing me, that she did not want to throw the term lesbian out with the dirty laundry. I absolutely respect that take up the term queer and lesbian at different points in my own life.

CM: When you speak about “we,” whom are you talking about? What is that community?

ER: There is a real difference between how I speak and feel now from how I did when I was working on LTTR. Then, I felt very concretely that I was involved in a diverse and active community of people who were identifying as queers and feminists.

CM: What do you think constitutes a community?

ER: A bunch of interrelated codependent relationships that have a shared set of goals and a diverse set of desires.

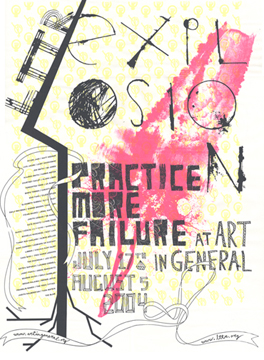

LTTR, Explosion, Issue # 3 launch at Art in General, 2004

CM: I ask this because the idea of community has been politicized so much within the mainstream LGBT Movement, which speaks about a singular community as if there was such a thing. How do you relate to identity categories or the word lesbian? Is it something you claim or are you post identity politics like so many other people?

ER: I am not post anything. I think to be post identity, like being post race, is ridiculous. As far as the term lesbian or queer, like I said, I can take up each of these terms quite comfortably with some strategic disidentification and I have always been like that. As we talk about these varying generations, I’m almost speaking about my generation in the past right now because LTTR constituted who I am, but there is now a turn in recent years to thinking about different temporalities so already my relationship to the idea of community has switched. Thinking about other generations, I think their mobilization of identities was much more straightforward. I was reading queer and feminist critiques of texts before I read the actual texts so I have always been turned on to a proliferation of originals. I have always felt a rub against language and categories while also being willing to take them both up. So when someone asks me how it feels to be the only political artist in an exhibition, I want to ask them what it feels like to ask such a stupid question but instead think, if you need me to be the only political artist in the show I can do that for you, I can be a lesbian, I can be an activist, even if my exhibit is actually working away from these categorizations, I am always willing to take the terms up because I don't want them to be thrown out.

CM: In my interview with Harmony Hammond she spoke about her concrete need to name, represent and identify lesbians as lesbians as well conditions of production, and relationships between sexuality and politics. Was it an LTTR strategy to reclaim and the category lesbian and giving it visibility?

ER: Totally, but only alongside other strategies such as shifting the meaning of the acronym LTTR with each publication or event. The project in general is referred to as “Lesbians to the Rescue,” but as much as we start from that naming, we also subsequently play with it. I have an infinite amount of respect for Harmony Hammond’s life and all of her work. I enjoy her so much. I think she is beautiful.

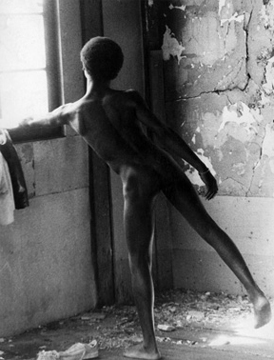

Emily Roysdon, The Piers Untitled # 2, 2010. Courtesy of the artist

CM: Much of your recent work is site specific or relates to how we understand and experience our bodies through space. Can you speak about these ideas about how you approach questions of gendering and queering space?

ER: I have been approaching those questions primarily through two words: “Use” and “regulation.” My most recent series of work started with the recognition of places being attached to ideas of proper use, particularly in regards to political speech. In a previous project I was looking at the post-industrial piers along the West Village in New York City that from the late 1960s to the early 1980s were heavily trafficked cruising areas as well as a diverse array of spaces that were off the legible grid of New York City. Many interesting lives were constituted and lost in these spaces. I spent a lot of time sitting down at the piers and am crushed by the hyper regulations taking over these spaces as they become new privately owned, but public appearing parks that occupy the entire waterfront of New York City. The work thinks also about the reverberations of this all over the city.

CM: Douglas Crimp mentioned he found your work of reclaiming these piers, which were sites of cruising of gay men, an interesting project for a woman or lesbian woman. How did you relate to this history in that space being that it is a history you do not necessarily own or descend from?

Emily Roysdon, David Wojnarowicz Project, 2001-2007. Courtesy of the artist

ER: I feel like I do descend from it because I initially entered that scene through David Wojnarowicz. He was the first artist I encountered that let me feel like I could have a viable life in the arts. My interest and entrance was really through his welcoming articulation of that space and I first started my “David Wojnarowicz Project,” reconceptualizing his “Rimbaud Series.”

My return to the piers stems from these earlier interests as well as my recent engagement with the work of Alvin Baltrop, who was a queer, black, bisexual with a proliferation of identities that died of cancer in the late 1990s. Looking at his body of work and thinking about the intersections with my interests as sparked through David Wojnarowicz and the piers as a world famous fantastical cruising site, I am engaging the way everybody imagines the piers and everything that actually happened down there.

I am interested in reclaiming the piers as a much more diverse queer space where there were women. I interviewed about thirty people about their experiences at the piers, and they all deny seeing women there so I am challenging both the idea that there were no women there as well as the idea that most of the people there were white. This is not true so people are painting a picture of the piers as one of white men with their pants around their ankles. I am not interested in that story as much as I am in the photographs Alvin Baltrop shot there for twelve years, which were never exhibited in his lifetime. He would walk into galleries and his work would be refused so I am more interested in how that racism has persisted in the gay community and remains part of the untold story, which includes this myth that lesbians were not there.

Photograph by Alvin Baltrop, source: http://baltrop.org

If you look at Alvin’s archive he has hundreds of pictures of people sitting out on the piers alone reading. There were all kinds of things going on there and I am more broadly interested in the fact that queers chose, and it was a choice, to go there. I made a book titled “West Street” because West Street is the street you had to cross to get to the piers. I am interested in this choice to cross the street and that sort of boundary, which takes different shapes, and in many ways is not there, except we queers know it is there, and we step over it and we go to a space to find many different things.

CM: Can you speak more about your relationship with David Wojnarowicz’s work and how he influenced you as an artist?

ER: Very early on he pushed important emotional buttons for me. I mentioned in this interview feeling emotionally repressed for a large part of my life. Encountering David Wojnarowicz’s anger and rage and the productivity of his anger alongside his experience in a community where all his friends were dying was a real emotional trigger for me. I realized I had a queer community and also identified with the community through the experience of loss and trauma and political rage.

CM: I’m interested in the way that public space and the body are represented in your work, and the themes we encounter in your work located at the piers in New York City and the public square in Stockholm. You seem to be claiming ownership of these spaces and queering them by insinuating the absence of bodies as well as by the insertion of bodies that “don’t belong” in these spaces.

Emily Roysdon, Sense and Sense, 2010. Courtesy of the artist

ER: In the piers work you are referencing I specifically chose not to have any bodies because I was thinking about non-monumental relationships to public space and spaces we all live amongst where history is made and unmarked. It was a different set of concerns with Sergels Torg, the public square in Stockholm. The strategy was to use a single figure, as I was concerned with ideas of the representation movement. The illusion of movement and the struggle of movement are all part of that video and set of images.

CM: Do you think of public spaces as gendered? Are you working to queer space?

ER: I feel like that is a fundamental element of my work that I do not necessarily choose, it’s always present, maybe not always at the forefront but absolutely always there. It may not be the driving set of concerns for an individual work but its fundamental to my overall set of concerns.

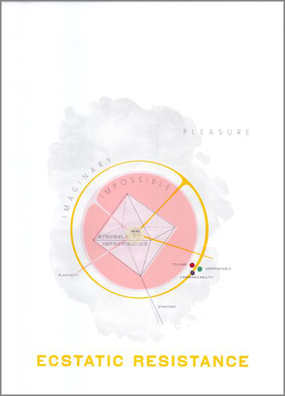

CM: Can you explain your concept of “Ecstatic Resistance”?

ER: I started to use the term toward the end of LTTR when I was asked to talk about the project. It was something I saw around me which began to represent a core set of interests in my work and the work of my peers. A crucial part of my intellectual life is relating to the work being made around me. I am not a solitary artist so I have always had that drive to look around and ask questions. This is where the term “Ecstatic Resistance” came from.

Emily Roysdon, Ecstatic Resistance Schema, 2009 (Designed with Carl Williamson).

Courtery of the artist

The idea itself is about mobilizing a vocabulary of the impossible, and the imaginary. Thinking about political representation, I located this idea and made a diagram of it, a schema where the impossible and the imaginary are two intersecting circles with struggle and improvisation as these two pyramids with movement at the core. It is all set within this field I call “the pleasure stain.” So it is about bringing this element of pleasure and performativity into resistance and thinking about plasticity, strategy and communicability, the unspeakable and telling. It is within this vocabulary of words I am playing with that I am thinking about a disruptive and destabilizing set of strategies to get beyond our limited imaginaries.

One of the examples I use to try talking about it is to think about the way the horizon of the impossible is always shifting. At one point, it was impossible to think black people would be free in America. At another, it was impossible to see women voting. Thinking about politics as a system of impossibilities, where people control the imaginary of what is possible to be, I started to think through “Ecstatic Resistance” as a force against that. The “ecstatic” is about an encounter to me; is an encounter where you get turned on just enough that your boundaries shift for a minute. I am interested in work that brings you to this place and presents an alternate reality as a possibility, works that somehow physically affect you.

CM: Is the ecstatic encounter a personal or interpersonal encounter?

ER: I think I am positing it as a relation between, an encounter you can have with a person, an artwork, or your own self I guess. It is the encounter that addresses our concept of the other, and my desire is to position that encounter as present and ecstatic because I want it to be developmental and challenging.

Emily Roysdon, Ecstatic Resistance Poster, 2010 (Designed with Carl Williamson).

Courtery of the artist

CM: Do the politics of this schema you just described respond to a set of policies or politics out in the real world?

ER: In a way I sort of want to say no because when I think of my friends who are activists, though I’m called an activist within the art world, when I look at my friend’s lives and their investment in activism I think in a way that I can’t claim that same space but the schema is absolutely inspired by, in the service of, and indebted to those kinds of projects. “Ecstatic Resistance” is interested in the viability of lives and questions the limits of what is intelligible right now. The queer politics I am most associated with center around gender queer and trans bodies, legibility, and the regulation of rights and access to services. Still I cannot say how my project affects these things.

CM: How has the concept of “Ecstatic Resistance” been enacted?

ER: It emerged as an exhibition at Grand Arts in Kansas City, Missouri, where I was given the early support to develop the project. It came to New York to X Initiative in its next iteration and I also turned it into a poster with three texts. One is mine, one is by Dean Spade and Craig Wilse and one is by Catherine Lord.

"Ecstatic Resistance" at X- Initiative, 2010. Courtesy of Emily Roysdon.

A great example of the project is Adrian Piper’s business cards. It’s impossible to paraphrase her elegance, but on a discreet business card you pass out one side says: “I guess you don't realize that I'm black I try to not point this out because it makes white people feel like I’m bossy and I tried to assume that you're not racist until you act like it but here is notice.” The other side says: “I’m alone, I actually want to be alone, this is not a part of some larger flirtation, leave me alone,” which points towards sexual harassment instead of an insipid racism. The business cards are an incredible gesture and get to the heart of the encounter, so she is really being drawn into and in drawing somebody into a different kind of encounter relationship and acknowledgment.

CM: You have a new project with a band MEN. Can you talk about MEN, your involvement and how it relates to your overall work?

ER: MEN is a lot of fun for me. It is absolutely unlike the other things I do, which is why it is entertaining. The project was started by Ginger Brooks Takahashi, JD Samson, Michael O'Neill and I. JD was in Le Tigre and Ginger is who I did LTTR with so there is a lot of cross over with previous projects. We all live in New York, are friends and wanted to start a band. I initially wanted to be a singer and had this idea of it feeling really good. I kept stepping away from the project realizing it was turning into a real band, as opposed to an art project because I do not know anything about music and am not going to go on tour, so my role now is to throw ideas into the band and work with them on the lyrics. They also use my images for the record covers.

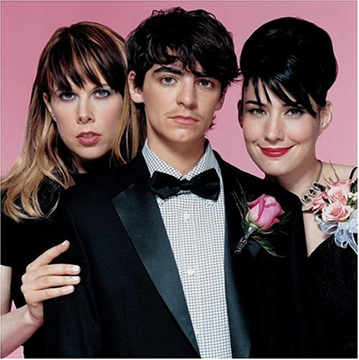

Michael O'Neill, JD Samson, and Ginger Brooks Takahashi: MEN

Courtesy of Emily Roysdon

CM: What inspired the band name, MEN?

ER: There are a few different answers for that. When we started the project, JD was working with Johanna Fateman from Le Tigre on a project called MEN, so when we combined projects they already had the name. Their reason was because they were doing this sort of self-help exercise for feminists where you think about what a man would do in a situation, which came from figuring out what to demand and negotiate for as they encountered misogyny in music venues while they were on tour. So they thought it was funny to call the band MEN.

My relationship to it, and why I think it is interesting is because there are all these different kinds of bodies on stage and you’re just taking this basic dominant human category and calling it into question through the performances and the lyrical content. I like taking this really fucking complicated queer feminist world and smushing it into this word that doesn’t want any of it so that’s how I can stand behind it.