hig

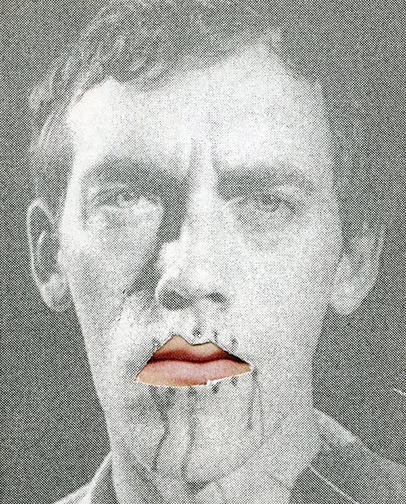

higSpeak, 2011, Ted Kerr

Time is Not A Line: Conversations, Essays, and Images About HIV/AIDS Now

Introduction by Theodore “Ted” Kerr

In 2010 a version of David Wojnarowicz’s video Fire In My Belly was censored as part of the exhibition Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Around the world artists, activists, along with galleries, museums and other art organizations responded by screening the video for free and sharing it widely online, hosting public discussions about David’s work and career, and organizing protests. In New York there was a march that started at The Metropolitan Museum of Art with people waving placards, chanting, and creating spectacles through their manner of dress and action. Within the crowd were people wearing masks of David with his mouth sewn shut drawn from the video Fire In My Belly. As powerful as these masks were, they struck me as being counter productive. David was being silenced again–even in the grave–oppressed by a government he understood as being implicit in his death, and we were joining him by being muzzled. To truly honor David, to fight for and with him, shouldn’t we have been chanting through masks with the mouths ripped open? Talking to some of the protesters I understood that they were trying to represent what oppression felt like for them. The protest was well covered by the media and the conversation about the censorship was sustained through out the run of Hide/Seek (helped in large part by artist AA Bronson asking that his work, Felix, June 5th, 1994 be removed from the exhibition out of respect for David and his work).

Looking back, this protest stands for me as the day where the second silence around HIV/AIDS was broken and when a public conversation about the AIDS epidemic started to take place again. Although David’s art is about more than his HIV status, the virus was very much part of his life and work. For the American right wing to silence David in 2010 was a whiplash flashback to the culture wars of the 1990s. It is fitting then that a protest in his name would bring people together–and back on to the street–preparing them for the onslaught of AIDS related cultural production to come.

If we can understand the first silence being President Reagan’s silence around AIDS during the epidemic’s first five years, I am suggesting the second silence is the twelve-year period that began in 1996 with the introduction of life saving medication that prompted a severe decline in the space HIV/AIDS took up in the public sphere, even while there were scientific and political breakthroughs, ongoing artistic and cultural productions around the epidemic, and many new cases of HIV infections. After much activism and loss, AIDS went from a public concern to a private experience. Services for people living with HIV were reduced and systemized, and generations grew up with AIDS in the ether–taking up little space in real life, even when they found themselves living with the virus.

A few years before the 2010 censorship of David’s Fire In My Belly, the second silence had started to be broken by the production and dissemination of cultural products by people who looked back at the early responses to the AIDS crisis. Daryl Wein’s Sex Positive–a 2008 film documentary portrait of AIDS activist pioneer Richard Berkowitz who famously, with Michael Callen, called for the use of condoms to reduce the transmissions of HIV early in the epidemic–being the most emblematic of the coming trend.

In the years that followed there were more films (We Were Here by David Weissman, 2011; United in Anger by Jim Hubbard, 2012), as well as books (Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father by Alysia Abbott, 2013; Fire In the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz by Cynthia Carr, 2013), exhibitions (AIDS in New York: The First Five Years, New-York Historical Society, 2013; Not Over: 25 Years of Visual AIDS, La MaMa Galleria, 2013) and even an uptake in ACT UP activities in San Francisco, Philadelphia, and New York.

Working at Visual AIDS, where we use art to remind the world that AIDS is not over and support artists living with HIV, I have been part of a team that has had a hand in promoting, disseminating and generating conversation around this rush of cultural production. From my vantage point it seemed as if have been culturally going through what I call an AIDS Crisis Revisitation. It has been amazing. Since then we have seen an increased involvement from people who were early responders to HIV/AIDS who for their own reasons had to leave the movement, more stories from long term survivors of HIV being shared, and cross generation conversations about HIV/AIDS taking place, amongst other things.

At the same time, something is missing within the AIDS Crisis Revisitation. In a series of conversations between media theorist and filmmaker Alexandra Juhasz and myself we have noted that largely absent–most obviously in the mainstream films (Dallas Buyers Club by Jean-Marc Vallée, 2013; How To Survive A Plague by David France, 2012; and the HBO adaptation of Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart by Ryan Murphy, 2014) –is the foundation of collectivism, intersectionality and feminism that the AIDS movement was built on. A past is being repacked to us–both those who were there and those who were not–and it is incomplete. Couple that with the second silence (the reduced circulation of AIDS narratives from the last decade) and you have an incomplete and faulty foundation from which to move forward.

It is from here that we begin the third issue of the We Who Feel Differently Journal with a focus on HIV/AIDS, a look at the recent past, and the current moment to both unearth the conversations had and the work produced within the second silence, and to share ideas and conversations that are taking place now:

Evoking invitation rhetoric through a series of powerful questions, artist Xaviera Simmons welcomes the reader to think about our present relationship with the virus in her essay Inching Towards A Contemporary Vision? Prompted by the poster “Your Nostalgia is Killing Me” by Vincent Chevalier and Ian Bradley-Perrin, Simmons offers us an opportunity to ask each other, and ourselves, “what do we talk about when we talk about HIV/AIDS in the 21st century?”

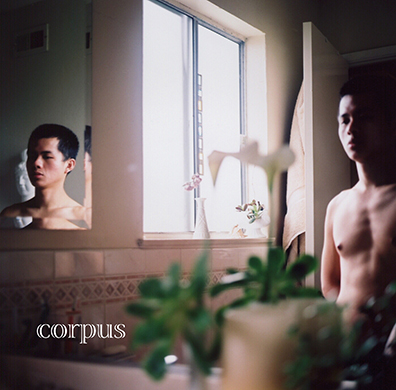

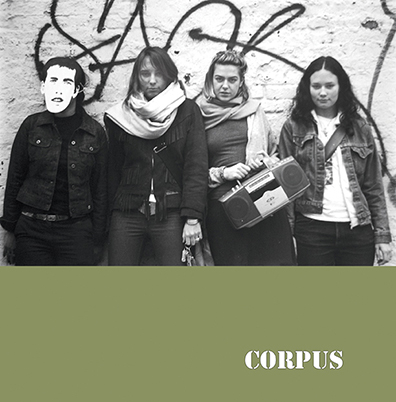

In A Wedge Holding Open a Very Small Window activist and performer Cyd Nova speaks with artist and educator Pato Hebert about Corpus Magazine, a ground breaking publication from AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA) that defied ideas around what prevention is suppose to look like. In the conversation, which is accompanied by pages from Corpus, Pato talks about how he and peers George Ayala and Jamie Cortez made use of the creativity around them to support those involved with Corpus to save their own lives and the lives of those around them during the second silence where there was not much space for conversation about HIV/AIDS to be had, and not a lot of attention being paid to those who were most at risk.

"Asserting a presence and gaining political visibility has been at the heart of HIV/ AIDS, then and now,” writes academic Aimar Arriola in his essay, Spectres of Iris De La Cruz. Arriola connects De La Cruz’s enduring legacy, to the current work being done by North American artist and activist Jessica Whitbread, Spanish collective Equipo re, and filmmaker Sally Gutierrez Dewar to speak about the important work being done by women–often living with HIV–for women living with HIV.

In When My Brother Fell, Again writer and respected activist Kenyon Farrow builds bridges between ideas of then and now, and the living and the dead, and wonders about the current state of AIDS activism guided by Essex Hemphill’s poem “When My Brother Fell.” Advocating for a more robust response to the ongoing AIDS crisis, Farrow passionately makes the case that current AIDS activism is suffering, in part as a by-product of resources being used to fight for “equality.” Meanwhile black young men–Farrow’s friends, and colleagues, and the movement’s possible next leaders, poets, and artists–are dying.

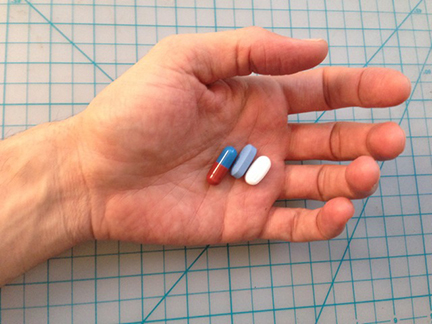

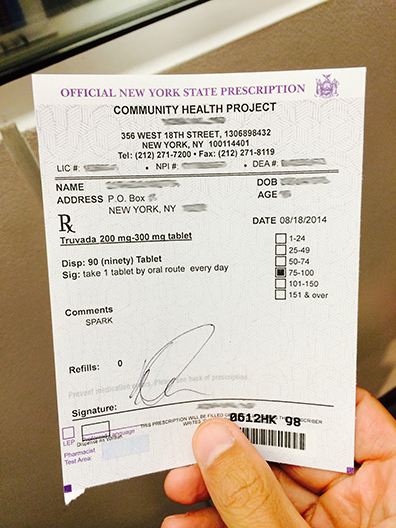

Issues of medication and mediation are

explored in

a frank conversation between academic Nathan Lee and

artist (and We Who Feel Differently creator) Carlos Motta, and then in a short story

by writer and performer Bryn Kelly. In There is Tremendous Ferocity in Being Gentle, Nathan Lee and Carlos Motta discuss pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) the ever-changing landscape of

sex, intimacy and community relations, in the face of Truvada being made

available for HIV negative people to prevent HIV. In the process of thinking about the present

and the future, within their conversation they come back often to that which

has not changed: trust, the need for communication, and the ways in which queer sex is

policed.

In Other Balms, Other Gileads Kelly uses literature to take us through a day in the life of a woman of trans experience struggling to make ends meet, satisfy her boyfriend’s various appetites, and negotiate the "pharmacopornographic era" she finds herself in. Along the way she reminds us that Gilead has a history beyond being the pharmaceutical company that produces Truvada, which for many may poetically speak to contemporary pressures and situations.

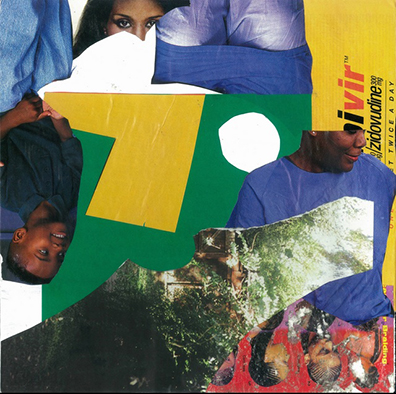

Accompanying each text are images by a variety of artists, many of whom are members of the Visual AIDS Artist Registry. The images should be seen not only in relation to the text they appear with, but as artistic expressions in their own right.

Emerging from the second silence, and influenced by the often healing yet incomplete AIDS Crisis Revisitation, this collection of essays, conversations, and images is not meant to be read as comprehensive. Rather it is a jumping off point to think about the issues and ideas the writers and artists are engaging in, while also inspiring the reader to think about all that is still not being discussed.

While HIV/AIDS begins with a virus, we can also understand it as an assemblage, not just self-tasked with replication, but also driven and made bigger through accumulation. Within the assemblage of the epidemic, time is not a line, as HIV/AIDS becomes the organizing principle, the lens through which many experience the world, and many try to make sense of it. This issue of the We Who Feel Differently Journal invites you in–as is the case with previous issues–to think and to feel differently.

Thank you to Carlos Motta for creating this platform, and Ella Boureau and Riley MacLeod for the editing assistance, and all the artists and writers involved.

Theodore

“Ted” Kerr

–August, 2014

↑Top

***

Inching Towards

A Contemporary Vision?

By Xaviera Simmons

Archive as Impetus, 2013, Xaviera Simmons

In Summer 2013 visual and performing artist Xaviera Simmons dove into the Museum of Modern Art’s “vast institutional history and archival holdings,” performing her research through long form public interventions that were part museum tour guide and part museum agitator.

As described by MoMA, the project, titled “Archive as Impetus (Not on View)” constructed a clear political line through the museum’s “early and contemporary exhibitions, archives, libraries, institutional correspondence, artist interventions, collection works, and present-day conflicts” with an aim of “opening up a dialogue.”

With that experience still

fresh in her studio practice and with Simmons still reflecting on her

engagement with the museum’s holdings, which include seminal activist art works by David Wojnarowicz, General Idea and Félix González-Torres, in the text below Simmons dives once again, this time not

into the institution as memory–but into an epidemic in the present tense.

– Ted Kerr

What happens when the immediacy of direct action

fades? What occurs when, for a multitude of reasons, a subject falls out of

favor with popular American media culture? What sustains when the local and

global media halts its rigorous coverage of the moment-to-moment workings of a

movement and when day-to-day protests and loud calls to action subside? More urgently, what has become of HIV/AIDS? And

what has become of its responses today?

What has happened to the individual and collective psyches surrounding the disease and its voices? And how is this psychological knowledge passed on to the bodies of those born after the apex of the AIDS movement, those who seemingly no longer see or face the visible life threatening, life ending repercussions that the virus once produced? Are the collective and personal narratives of the friends, family members and confidants of those living and/or passing with the virus no longer as immediately relevant to the general population? Those whose memories are folded away on a daily basis into the privacy of personal and familial narratives? Where is our collective consciousness surrounding HIV/AIDS with the passing of time, advancements in medical technologies and care and the ever shifting cultural gaze? What has happened to those documents, texts, films and documentaries that lay seemingly static and frozen in steady retrospect dedicated as memorials?

What do we talk about when we talk about HIV/AIDS in the 21st century? What happens in and to our bodies when we see “AIDS,” when we see “HIV”? Who is the audience/receiver and under what circumstances are they receiving the implications of the letters: A-I-D-S? What direction does the compass lean towards when we contemplate HIV/AIDS today? Which labels do we identify most with in the spectrum of personal and sexual desire and preference? What is our relationship to the virus as living positive with it or as a known negative? Did we experience the loss of a lover from the disease or has the virus barely touched our immediate circles? Again, what do we talk about when we talk about HIV/AIDS in the 21st century?

Disclosures II, 2013, Shan Kelley

What occurs in our brains as we encounter these letters? What specific emotions, what memories, longings or desires enter the breath and bloodstream once these letters come into consciousness today? Are those letters linked to memory/nostalgia or do they link to a present moment perspective? Did we or do we still belong to a support group, action network, documentary film or artist collective, or other such organization whose purpose was or is now to support, fight and win the battle against HIV/AIDS?

Are we friends, neighbors or allies with any of those working on the frontline today? Where and how do we locate the frontline in HIV/AIDS action and dialogue today? When we talk about HIV/AIDS do we still wonder if the virus will reach us or do our thoughts go towards those specific faded images of men and women whose bodies we watched sink into beds that housed their longings, lusts, dreams and desires? Or perhaps we comb our brains for those memories that have attached themselves to the narrative of the virus in some other way, again perhaps as memory? Memories that make way for some kind of compassion; memories that once activated closer towards yearning, where yearning flows molasses like, towards nostalgia; a complicated, frustrating and difficult nostalgia but a nostalgia none-the-less?

Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me!, 2013, Vincent Chevalier and Ian Bradley-Perrin, for AIDS Action Now’s poster-VIRUS

Do we even have a collective definition of nostalgia and if so what is it and how do each of us make use of it? As nostalgia settles in, where in the body is the space for contemporary thought, voice, vision and action as they relate to HIV/AIDS today? What are the methods we use in contemporary culture to enter into a dialogue with this overwhelming, sometimes underwhelming and often unknown virus?

Is it rather easy to sliver through the silences surrounding HIV/AIDS in the contemporary sense? Do we tend to take our conversations surrounding the disease in simple, measured, hushed, awkward, uncomfortable and meager doses? Do we often see the practitioners of the HIV/AIDS movement as critical and important heroes of decades passed, except where/when fashionable? What place does their work have in our real thought and who has stepped up to grab hold–or rather–meld with their places on the front lines today? Where are the spaces for activists of various generations to speak, to share, to collaborate and to strategize on collective memories and contemporary action surrounding the disease?

For most of us, most of the time, especially those of us that are American and uninfected–or supposedly less at risk of infection–is it through a nostalgic lens that we have any modern engagement with the virus, if at all? Do our personal and collective entry points to the virus tend to take shape in some of the following ways: Past activist activity (the frontline vision); contemporary Africa (according to most statistics, over twenty three million Africans are living with the virus); associations with African American males (the population with an infection upswing due to lack of resources and education); and film dramas and docudramas (How to Survive A Plague, Dallas Buyers Club, United In Anger, We Were Here)? How and where do we construct a more stable, more contemporary platform to bring forth a broader, more comprehensive vision of HIV/AIDS into our common, mainstream, collective vision? How do we construct a vision for viewing HIV/AIDS in the present tense, in the contemporary sense of the disease? With what little coverage is being dolled out via media outlets and with stigma of the disease still very much prevalent worldwide, how do we negotiate methods surrounding simplistic, often ill-informed views regarding HIV/AIDS today?

Most of us sit still surrounding our own discomfort with various aspects of the disease? What would it look like to dissect the bones of the virus as it relates to our contemporary day-to-day life, to get at the marrow and cross into those unknown territories of thought, speech and action towards a contemporary collective vision of a world still living with HIV/AIDS?

Xaviera Simmons’ body of work spans photography, performance, video, sound, sculpture and installation. She defines her studio practice as cyclical rather than linear and rooted in an ongoing investigation of experience, memory, abstraction, present and future histories. In 2014-2015 Simmons will exhibit and perform in numerous national and international solo and group exhibitions. She is the recipient of major awards and fellowships.

***

A Wedge Holding Open A Very Small Window

Pato

Hebert talks to Cyd Nova about Corpus Magazine

Altered details from “Burning Bush,” 2003, photonovela, Jamie Cortez, Corpus Magazine cover, Winter 2004

Corpus Magazine was like a

dream; a beautiful publication made to be kept–a physical

object whose value is unquantifiable. Not only was Corpus

aesthetically gorgeous, but

it also eschewed the narrative of HIV that

we are all so used to: the pendulum swing between resilience and irresponsibility,

with HIV positive reality stars and celebs “doing”

AIDS work in Africa or similar stories.

Corpus was a

collection of fiction, memoir, art and journalism–by and for

people affected by HIV, and it centered on the lives of gay/bi men and people of

color. Corpus didn’t promote

drug regimes,

supposed public health agendas, or upwardly mobile lifestyles, as many publications that

circulate within the AIDS world often do.

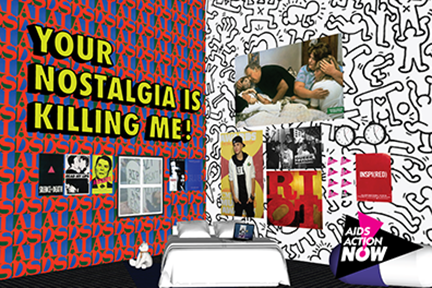

Put out by AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA) from 2003 to 2008, Corpus was a labor of love for friends, colleagues, and long time cultural workers, George Ayala, Jaime Cortez and Pato Hebert. In the interview below I ask Pato, an intermedia artist and an associate art professor at the New York University Tisch Department of Art and Public Policy about his involvement with Corpus, how the publication came to be, and the impact it continues to have.

When Corpus folded I was just coming into my activism around HIV. Now I am involved with the incredible and envelope pushing non-profit, St. James Infirmary, a clinic for current and former sex workers, and in 2012 I was part of the group that reformed ACT UP in San Francisco, now on hiatus. Through these experiences I can appreciate the work that went into Corpus. There are a lot of HIV related issues to challenge and call attention to. What I like about Corpus, is that it didn’t seek to solve any crisis, it simply worked against the idea that some people are unimportant and that it is OK for them to disappear with their stories untold.

In this interview Pato and I also discuss the medicalization of bodies at risk, the nostalgia that people have for an AIDS movement that existed before Corpus, and what that means for the movement now.

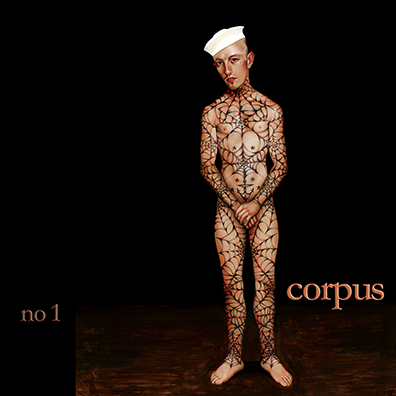

“Tattoodle Hybrid”, 2001, acrylic on board, Timothy Cummings, Corpus Magazine cover, Summer 2003

Cyd Nova: Corpus was an incredible magazine the likes of

which I’ve rarely seen, much less as a project

of a non-profit. How did it come into being?

Pato Hebert: Corpus first began in 2002 when George Ayala invited me to join the education department at AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA). In addition to me guiding a team of talented community-based HIV prevention folks and developing large-scale outdoor media interventions, George wanted us to revitalize prevention discourse and action with gay men through publications. Corpus emerged from conversations with George about what we felt was missing in the world of AIDS at that time. We both knew Jaime Cortez and felt that he was the perfect person to help us conceive and launch this project.

Collectively, we wanted to work from, with and across communities of color, with visual artists and creative writers, in a high-profile HIV prevention context yet with a sense of what I call “having your nose on both the block and in the books.” We wanted Corpus to pulse with a lot of different kinds of sensibilities, vernaculars, tonalities, reference points and priorities. It had to look, feel, read, caress and bite like something different. We knew Corpus needed to be grounded in a harm-reduction approach that would counter the outrageous pathologizing and patronizing of queer men of color that were rampant within the AIDS industry. Corpus needed to push hard against the deficit frameworks that were being used to describe queer communities of color and instead saunter, speak, and spit in forked tongues from within those very communities. Such evocations had always been in play, but communities just had never had the resources of a large AIDS entity to marshal on our behalf, nor the platform through which to do that kind of national in-reach.

CN: What kind of relationships did you have with Jaime Cortez and George Ayala when the magazine was started and do you still continue to work together?

PH: I met Jaime in the mid-1990s when we were both living in the Mission District in San Francisco. We were in the orbit of Proyecto Contra SIDA Por Vida, a queer Latina/o HIV services organization that served as a kind of community hub and cultural catalyst in the old Mission. We realized we loved art, language, humor and irreverence, and we’ve been exploring these things together ever since. I met George around the same time, when he was visiting the Bay Area from New York. Then we began working together in 1999 when we were both living in Los Angeles. Our first joint effort was developing a large-scale HIV prevention public art project with communities of color in L.A. County: HIV is still here. SO ARE WE.

CN: How did you all work together to decide the content?

PH: There were seven issues of Corpus altogether, each with its own guest editor. Jaime edited the first two and co-edited the sixth. Laurence Padua, Robert Reid-Pharr, Alexandra Juhasz and Andy Quan were the other editors. Guest editors identified an organizing theme and selected the majority of the content based on their thematic interests and creative and political networks. I also had strong input, making suggestions to help fill in thematic, tonal and other gaps. I also co-edited two of the issues. Once overall themes and contributors were mapped out by and with the guest editor of a given issue, I would brief George and we would problem solve any potential gaps or concerns. Once the near final work was laid out, I would have George do a close review, along with the copy editors, translator Omar Baños, and APLA’s Executive Director Craig Thompson, without whom Corpus could never have seen the light.

CN: I came across the quote “We shouldn’t put a condom on a conversation” in Corpus. What does that mean to you? In searching for where I found that quote I discovered an entire issue of Corpus without the word “condom” used even once, and I want to say, that is a pretty incredible feat.

PH: I learned that idea from my colleague Ray Fernandez, a brilliant thinker and empathetic organizer who ran our youth program at APLA for many years. I think Ray always pushed us to talk more openly and fiercely about what really matters and to be unapologetic in our desire and ever critical in our politics and efforts. In addition to minding the nuts and bolts of community-driven approaches and harm-reduction strategies, good prevention requires candor and courage, non-judgment and connection. Condoms can help keep us alive, but public health approaches cannot if they shield us from the rich and raucous truths of our lives.

“Kelly With a Friend at Cerrito del Carmen,” 2006, inkjet print, Tom Williams, Corpus Magazine cover, Fall 2008

CN: Corpus felt like a magazine written for queers who weren’t necessarily upwardly mobile–a lot of the work featured in those magazines was by people of color, femme men, transgender women, sex workers and proud sluts. What kind of community built around the magazine?

PH: All kinds of communities. Some were trying with all of their might to be upwardly mobile, but were confounded at multiple turns by prejudice and stigma. We had a contributor deported. I once tapped into our network, inquiring about a possible guest editor, and another time about a photographer, only to discover that they had both died from AIDS. Two of my former coworkers, both gay Latino men, killed themselves during the Corpus era and a third colleague left notes at work saying he would commit suicide too. Fortunately he did not. I heard the police shoot and kill a young man on my street in Los Angeles. Many of our youth group members were beat up and bashed en route to work, school, home. At work, school, home. Too many community members sero-converted. A ton did not. Some were arrested, without shelter, hungry. Some invented new dance moves, poems, ways to cuddle and kiss, dreams for their future.

Corpus became a mainstay in the lobbies and meetings rooms of countless AIDS service organizations and on the campuses of numerous colleges. Corpus found home (and came from) radical faerie gatherings, gay bars, strategic planning sessions, pride gatherings, research journals, the rez, dance floors, hustler sites, border crossings and sex clubs. Once, copies were even confiscated from a Centers for Disease Control (CDC) gathering in Atlanta. Another time we learned that prison officials were concerned that Corpus was being used as porn. My mom would ask me when the next copy was coming out. How do we understand the ways in which these communities assembled and disassembled, knew and unknew, imagined and unimagined and reimagined and asserted themselves in and through Corpus?

CN: So much consumption of media now happens online. What do you think that Corpus–being a physical magazine–provided that the Internet can’t and vice versa?

PH: Corpus emerged in 2003, just before the explosion of social media, which eventually became far more ubiquitous by the time the last issue was released in 2008. Hard copies of Corpus were a visceral and episodic encounter. There really wasn’t anything else quite like it in the cultural landscapes of the HIV, art, queer or colored worlds. Folks were famished for complex, vulnerable, playful, nuanced and sassy stories about queer men of color compiled in book form. People would cherish their copies and share them with friends, colleagues, tricks and lovers. We got requests for copies of Corpus from men living in prison, outreach workers from small neighborhood organizations, professors designing groundbreaking courses in sociology, ethnic studies, media studies and community health. Not everyone had a cell phone when Corpus first arrived, and very few of those phones had cameras. Now almost anyone with a phone and a bit of electronic savvy can post as many selfies, stories and sensibilities as they want to the world. So, although it wasn’t that long ago, Corpus addressed a gap in representation that has since begun to shift. Still, circulation is not either/or. Corpus continues to live on online, as free low-res PDFs available on APLA’s site and as used copies for sale in the digital marketplace.

I

think the Internet offers the potential gifts of discovery, speed and agility,

even as it can be terribly

distracting, draining and disorienting. So lately it’s

been fun for me to think about a new kind of multi-media publication that could

respond to our current hyper-mediated moment

while massaging the edges of what’s

necessary and possible at this time.

Corpus, Vol. 3, No. 1, Fall 2005, Editor Robert F. Reid-Pharr. Art by Viet Le, Cibachrome print, from the series Pictures of You

CN: What is the story behind Corpus folding?

PH: The economic crash of 2008 made fundraising extremely difficult in the AIDS community and in NGOs more broadly. It was a very painful time for organizations trying to keep their doors open and the most basic, direct services alive. Corpus was unable to survive in the face of these deep structural challenges.

CN: What have been the long-term impacts of Corpus on the Los Angeles queer community?

PH: That is a great question, and difficult to assess, made more so by the fact that Corpus was really national in scope, including several issues being jointly produced with Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York. Content contributions came from all over the country, and copies were distributed nationwide in the thousands. It’s impossible to say how many infections Corpus might have helped to prevent, or more painfully, how many it could not avert. We cannot say how many conversations it provoked, or how many tears or smiles it engendered. And it’s disheartening to look at the contemporary AIDS Industry and see so little of the creativity, coalition, conviviality, criticality and fierceness that marked so much of the first fifteen years of our collective response to AIDS in the United States, the wellspring that had sewn the seeds for Corpus.

But as my colleague George likes to say, Corpus was really a wedge holding open a very small window in the larger structure of the AIDS response. Its job was to present our needs and tell our stories and generate convergence during the terrifyingly conservative years of the Bush regime, when our AIDS efforts were set back so severely by abstinence-only approaches and extreme restrictions on programmatic content. And we know from the survey feedback that folks did think Corpus was full of innovative ideas, was relevant to preventing the spread of HIV among gay men, and that it was useful in their own work. The APLA publications continue to be taught at universities across the country. I talked about the publications with students and faculty at the University of Connecticut in February. Jaime and I presented Sexile at SF MoMA’s “Visual Activism” symposium in San Francisco in March. I’ll be writing about the work this summer in relationship to community-based and collective art responses to AIDS. And early next year I’ll be talking about Corpus as part of the Virus series organized by Alexandra Juhasz at Pitzer College. So the work is still very much alive in the world, even if I no longer have the pleasure of prepping envelopes and boxes for shipment each night.

“Untitled”, 2001-2007, Emily Roysdon, Corpus Magazine cover, Spring 2006

CN: You designed Corpus and today you are a visual artist focusing on photography and installations, what do you think visual art brings to the HIV dialogue that text might miss?

PH: As

visually sumptuous as Corpus

could be, it was always very much a textual artwork as well. The poets, fiction

writers, memoirists, essayists and conversationalists were as integral to the

complexity and success of the project as were the visual artists. We also had a

four edition literary series by and for black queer men and allies, and produced two comic

books. I do a lot of

text-based visual artworks, as well as graphic design. So art and text tend to

infiltrate one another all the time in my life and practice. In the context of

HIV, art opens up a space that might not otherwise be so accessible. It makes

legible our sense of desire, struggle, revelation, subtlety, uncertainty, fear,

elation, loneliness, interconnectedness, power. Art also cuts against the

tyranny of empiricism. Art can be profoundly conceptual, and deeply logical,

while science can be magnificently creative as it probes the ineffable. But we

cannot adequately face AIDS with anything less than our full humanity,

and without art we are impoverished beyond all bio-medical repair.

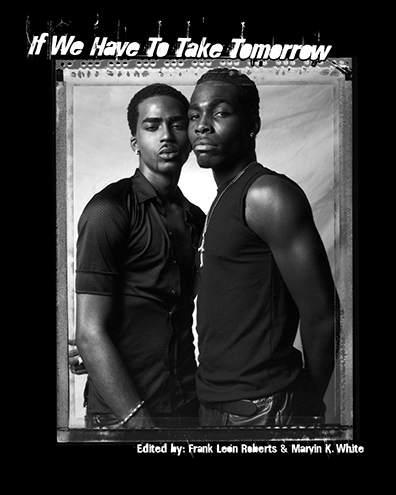

"Untitled," 2003, digital photograph, Gerard H. Gaskin, If We Have to Take Tomorrow, 2003

CN: You helped plan and moderated a panel recently on AIDS nostalgia. What are your thoughts on the recent uptake in looking back?

PH: I think it’s really important that we know our histories. I think it’s equally important that in our efforts to piece together our histories, we do not rush to canonize and flatten, and we do not simply re-inscribe old centers in new forms. I think we are in a crucial period of actively remembering. AIDS has been devastating. And yet, thankfully, perhaps not so completely debilitating. How do we truly comprehend this resilience–yes, that of the virus, but also that of our shared selves? It is so important to contend with this, AIDS and our resilience, publicly and privately, collectively and conceptually, spiritually, philosophically, sexually and politically, painfully and impossibly, and with all the honesty, temerity and tenderness we can muster. The question, as always, is whose memories take precedence, whose memories prevail? Which is to say, whose present needs matter most? The answer should be all of us matter most. But operationalizing that, which is to say practicing genuine equity, ain’t no joke.

CN: What are your thoughts on the current priorities of AIDS Inc?

PH: I feel hopeful that more people than ever who are living with the disease are gaining access to life-saving medication. I feel hopeful that prevention is being understood more holistically, and also that we are continuing to break down old, false splits along the continuum of prevention and care. I feel motivated and nourished by the coordination afoot among global movements of key populations who are most impacted by HIV. Yet I am still exasperated that the broader global community has not made it a priority to render capitalism less important than our very collective lives, that we’ve not devised value and access systems to make medicine free and accessible to all who need it. I am deeply concerned that we are racing toward a narrowing bio-medical approach to HIV that, in eschewing proper attention to social and cultural factors, will inevitably lead to a rise in infection rates where science, specialized experts and bureaucracies control responses that are best shaped, driven and owned by communities. I am encouraged that the distinction I just made is a false and faltering one, as so many stakeholders are also community members and global and regional movements are gaining strength, fed by tireless local efforts. But I am dumfounded that condoms and lubricants are still unavailable in so many communities across the world. I am daily disappointed and disturbed that queer men and transgender people, sex workers, people who use drugs, migrant populations and ethnic and religious minorities, poor and working people and people living with HIV are increasingly stigmatized and criminalized. Pills are crucial. They will never be enough.

“My Lovely,” 2004, digital photograph, J. Diaz, Corpus Magazine cover, Fall 2004

Pato Hebert is an artist, educator and cultural worker. His work explores the aesthetics, ethics and poetics of interconnectedness. He teaches as an Associate Arts Professor in the Art and Public Policy Department at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. He also contributes as a Senior Education Associate with The Global Forum on MSM & HIV (MSMGF). His artwork can be seen at www.patohebert.com

Cyd Nova is a sex worker, activist, writer and he is the Programs Director at St James Infirmary, which is the best little whore clinic in San Francisco, and currently the only peer-run clinic in the US. Currently, he is working on a gay FTM porn company called Bonus Hole Boys, researching San Francisco's sex worker history and living in Oakland. You can read some of his writing, which has appeared in the Rumpus, Pretty Queer and 'The Collection: the New Transgender Vanguard' on his website at cydnova.wordpress.com

***

Spectres of

Iris De La Cruz

By Aimar

Arriola

Iris De La Cruz, AIDS activist and former sex worker activist is interviewed on women and needle exchange, undated. Produced by GMHC. From AIDS Activist Videotape Collection, NYPL.

I

was deeply moved by something said during the opening minutes of the

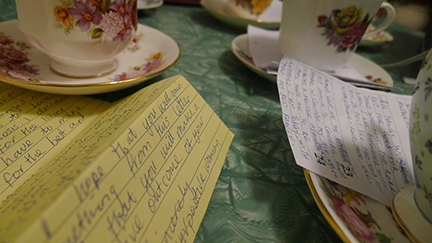

presentation of Jessica Whitbread's community art project and book Tea Time:

Mapping Informal Networks of Women Living with HIV/AIDS, organized

by Visual AIDS and the New School’s Queer

Collective. During the event, which took place on March 19, 2014 at the New

School's Lang Café, Ted Kerr–introducing

an excerpt from a video interview with Iris De La Cruz (1954-1991), the now

legendary Latina HIV activist about whom I have only recently learned–spoke of

the need to avoid a binary distinction between the living and the dead. That

experience and the invitation to comment on Jessica's project here challenged

me to confront the many times I have more or less consciously fallen into such

a binary division, giving precedence to the words and actions of those of us

who have the (dubious) privilege of still being alive. In her videographic

speech, Iris De La Cruz–who

tirelessly fought to ensure that other women were not, as she herself had been,

left without options or resources–discussed

the difficulties of being an HIV-positive woman in an environment dominated by

gay men, that is, within organized AIDS activism. She specifically addressed

the need for spaces where poz women can interact in a caring environment:

"I got a lot of love and support [from the gay male community] but I also

had women's issues. I needed to hear what other women had to say. That was

really important. When I walked into a room and there were twenty five women

in this room and they were all zeropositive or were dealing with AIDS, all of a

sudden I wasn't the only one." As if politically possessed by the spectre

of Iris De La Cruz, the ultimate aim of Tea Time is to contribute to the

construction of those spaces.

As Jessica Whitbread explains, Tea Time began as a personal journey into her own understanding of HIV in relation to gender. She was interested in finding a way to build connections between women with HIV living in diverse communities in Canada. To that end, she devised a community-based research project that joined women living with HIV together using what she refers to “the Tea Time method”. The Tea Time method relies on the feminist and queer strategy of re-signifying “tea time,” whose origin is steeped in colonialism and sexism, as a space for empowerment. After an initial research phase, Whitbread’s Tea Time initiative has grown into a worldwide open-source community arts project. Its vision resonates in other recent initiatives like The Future of Feminist Tea Party by Quito Ziegler and the Jane Austen-inspired DYI feminist tea parties organized by The Austenettes in Spain. Whitbread’s project, though, is the first to make use of the cultural ritual of tea time to address the issue of women living with HIV/AIDS.

I

would like to clarify at the outset that my response to the invitation to

comment on Tea

Time

is conditioned by a number of things. First, my privileged position as a queer-identified, HIV-negative

biological man. I in no way intend to act as if I knew what it means and how it

feels to be a poz woman. In her presentation, Jessica shared the concerns of

her designer friend about “occupying a space that didn't

correspond to him” when he was asked to design the

cover for the special edition of the book. That somehow spoke to me. Also

pertinent to my response is having attended, over a period of roughly a month,

a fairly large number of meetings, talks and other events–including the presentation of Tea Time–held in spring of 2014 in New York

while I was there as the 2014 curator in residence at Visual AIDS. These events

included an exhibition on the history of activism in the city, which was

accompanied by a parallel program of events geared to providing insights on the

participation of the Latino community and women in ACT UP, among other topics.

As part of my research, I have also had private conversations with artists,

scholars and activists on aspects of the visual, aural and political cultures

of AIDS. My understanding of Tea Time takes place in this broader

context.

Tea Time (Toronto), courtesy of Jessica Whitbread

Iris De La Cruz’s spectre took hold of the room during the Tea Time presentation and warmed it during the panel discussion afterwards. The participants in the discussion were four women living with HIV–Kia LaBeija (USA), Teresia Otieno Nojoki (Kenya), Darien Taylor (Canada) and Jessica Whitbread herself–all of whom are featured in the book. I was startled, and moved, to hear native New Yorker Kia LaBeija–a young multidisciplinary artist who works in photography, performance and installation–say that until she was in her twenties she had never met another poz woman, thus exposing the failure to provide unlimited interaction and full connectivity promised by the 21st century global metropolis. Iris’ spectre also revealed, in my understanding, one of the main issues underlying Tea Time, an issue that lies at the core of the debates on AIDS and its cultural production which has been the focus of my work this past month: the need for political representation of the “invisible subjects of AIDS,” that is, those overshadowed by the still prevailing structures of class, race and gender.

From the beginning, the fight against AIDS has been a fight for visibility. Asserting a presence and gaining political visibility has been at the heart of HIV/ AIDS, then and now. The visual subject of AIDS–its political subject par excellence–is still represented as a gay white man, and that has overshadowed the important HIV/ AIDS work performed by other political subjects. This issue was addressed by Deborah B. Gould in a 2012 article on the issue of alleged racism in ACT UP. Gould argues that “although the movement’s rhetoric and self-understanding articulated a commitment to fighting for all PWAs” it ended up “privileging the concerns of white, middle-class, gay men over those of others with HIV / AIDS.” Those “others” were primarily women–lesbian or straight, poor or middle class–and communities of color.

After her apparition at Tea Time, Iris De La Cruz’s spectre was spotted again two weeks later, during a panel discussion held in conjunction with the New York Public Library’s Why We Fight exhibition. The panel addressed the crucial role that women played in the various chapters of ACT UP. During the discussion, the expression “invisible women” came up a few times in reference to HIV-positive women dying from infections that were not initially included in the Centers for Disease Control's (CDC) definition of AIDS. That term was also used in a reference to Gena Corea’s The Invisible Epidemic: The Story of Women and AIDS (1993). That book, which the presenter described as “a book nobody remembers,” tells the previously untold story of women and the AIDS epidemic. As the panel pointed out, it was the tireless efforts of women in ACT UP that forced a change in the CDC’s definition of HIV/ AIDS. They were the ones that got poz women to be included in clinical drug trials. Until 1992, gynecological symptoms associated with HIV were excluded from the CDC's list of opportunistic diseases. Women succeeded in persuading the CDC to include cervical cancer and other opportunistic diseases typically associated with women, and to expand the CDC's standards of care and prevention. A clip of Iris was among the materials shown on full screen over the course of the evening, a cinematographic embodiment of all the invisible subjects of AIDS and evidence that AIDS archives are by no means ghosts of the past, but rather political tools for present action.

Weeks earlier, Kelly Cogswell had brought up the prevalence of men in major AIDS activist organizations at the presentation of her book on the history of the activist group The Lesbian Avengers. The event–which I was lucky enough to attend–was held at the Bureau of General Services Queer Division, a bookstore and event venue as well as a political tool in its own right. Amidst readings from the book, Cogswell recalled that one of the triggers for forming the group was having wandered into a couple of ACT UP meetings at Cooper Union and thinking “there were so many people, so many men.” In the book, she also describes “trying a Women’s Action Coalition meeting” but finding it “stuffed with good-smelling SoHo types who had never applied to Medicaid,” thus adding the issue of class to the problem of political visibility.

The making of Tapologo with film directors and members of the community, 2008, photo: courtesy of the artists.

Other social, activist, and artistic initiatives in which women work against AIDS–initiatives that I have had the privilege to come into contact with thanks to my own collaborative work on the cultural implications of the pandemic in the “global South”–strongly resonate in Tea Time. Tapologo (Spain/South Africa, 88 mins., 2008)–a film by Sally Gutierrez Dewar, who is a graduate of the Whitney Museum ISP program and a friend, and her sister Gabriela–documents the work of an informal network of HIV-infected women. Tapologo is a community project started in 1997 by a group of poz women in Freedom Park, a squatter mining settlement in South Africa. The project mobilizes retired nurses, social workers, doctors, and religious leaders marginalized by the church, as well as sex workers. Each meeting of Tapologo is built around collective chants, group meals, and long conversations where participants express often taboo desires and fears as part of the healing process –very much in the spirit of Tea Time.

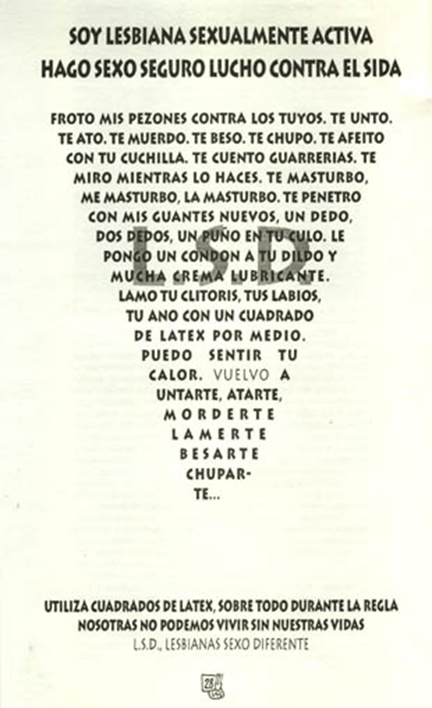

We showed the film in Seville, Spain, last October at a seminar/meeting organized by the collective Equipo re, whose members are Nancy Garin, Linda Valdes and myself. The main goal of the meeting was to look back at the political legacy of AIDS activism in contexts such as Spain and Chile, which we acknowledge as a source of radical pedagogy capable of re-empowering political work in the current situation of global crisis. The event was also an occasion to share and recognize the work of the many women engaged in the fight against AIDS, women at the core of a range of struggles: early queer activism in Spain–as represented by the collective LSD–providing care to drug users living in the street, and the current fight to decriminalize sex work. Many participants recalled that the first to respond to the emergence of AIDS and to its disastrous handling by the Spanish government in the mid-80s were women–the mothers, sisters, friends and girlfriends of those affected early on. The gay community, on the other hand, kept to itself, fearful of a new social stigma that might imperil the freedom and recognition gained after the fall of the Franco regime.

AIDS prevention poster, LSD, Spain, mid 90s. One of the first campaigns in Spain specifically aimed at lesbians.

Someone at the panel on women’s participation in ACT UP said, “It was the men who opened the door to the fight, but women will be the ones to bring the crisis to a close.” As a queer individual doing research, curatorial and activist work related to the visual and performative cultures surrounding AIDS, I also hope to make a contribution to the cause. In the spirit of Jacques Derrida when he argues for conjuring the “Marxian spectres” to counter the capitalist dogma that travels the world, I urge us to reclaim the spirit of Iris De La Cruz and many other tea-timers, both dead and alive, who have contributed to the fight against the neoliberal management of AIDS and of life itself. May they possess us all as we continue to build a more democratic present in which all political subjects, regardless of identification, can opt for visibility, care and dignity.

Aimar Arriola is an independent curator and a nomadic queer individual born in the Basque Country, Spain. His work involves research, memory and identity politics, as well as an embodied approach to the archive. In Fall 2014 he will start his doctoral research on the visual and performative production of AIDS in the “global South” at the Department of Visual Cultures, Goldsmiths College, London.

***

When My Brother Fell, Again

By Kenyon Farrow

Charles’ shoe, 2013, Ted Kerr

When my

brother fell

I picked up

his weapons.

I didn’t question

whether I

could aim

or be as

precise as he.

A needle

and thread

were not

among

his things

I found.

—Essex

Hemphill, When My Brother Fell (For Joseph Beam), 1992

Essex Hemphill wrote When My Brother Fell (For Joseph Beam) in part as a re-sponse to the death of his friend, black gay writer Joseph Beam, but also as critique of the passive memorializing of people dying of AIDS through the AIDS Memorial Quilt (initiated in 1985) and the adoption of the Red Ribbon as the international symbol of AIDS awareness (launched in 1991 by the Visual AIDS Artist Caucus). Both writers/activists were brought down by the hand of AIDS, Beam in 1988 and Hemphill in 1995.

Memorials like the AIDS Memorial Quilt, the Red Ribbon and World AIDS Day however, have helped mobilize people who are impacted by the loss of friends and family to the virus. They also give people, who may not have a direct connection to the mass deaths, a way to feel empowered or to do something–even if that something is only to wear the ribbon or visit the quilt.

For Essex Hemphill these memorials were not enough. Writing, publishing, speaking, and organizing were the kind of hard work and the “weapons” he was committed to use to fight AIDS and the political crisis it produced. By 1992, the time when Hemphill's poem was written, many gay and lesbian activists had already taken up similar approaches, but less so to fight against AIDS than to advocate for the inclusion of sexual minorities in civil society–as witnessed through the development of the pillar issues of the main-stream LGBT movement: military inclusion, marriage equality, nondiscrimination laws, etc. In fact, in her famous essay “Where’s the Revolution?” (July 1993), black lesbian writ-er/activist Barbara Smith already forecast what had occurred in the movement: "...since the eighties, as AIDS has helped to raise consciousness about gay issues in some quar-ters of the establishment, and as some battles against homophobia have been won, the movement has positioned itself more and more within the mainstream political arena."

Bluntly said, the ability of the mainstream LGBT movement to gain cultural acceptance of gay, lesbian and (increasingly) transgender issues happened on the back of the AIDS crisis. The AIDS movement redirected activist gays and lesbians, whom were already part of varying Leftist movements (anti-war, nuclear proliferation, feminist, welfare rights, prisoner’s rights) to take up a political fight. Under the weight of state violence and the neoconservative reframing of some social justice issues, the AIDS crisis brought more people out of the closet and into the streets. (Since the 1970s there was already a grow-ing “gay rights” infrastructure being created, but the HIV/AIDS crisis in many ways cata-pulted the movement into high-gear, most famous of course is the AIDS Coalition to Un-leash Power (ACT UP) founded in NYC in 1987.) These new activists created resources to demand a proper governmental response to an overwhelming health crisis and also designed a greatly expanded infrastructure of institutions to push against the impact of homophobia and for social, political, and economic equality.

Thirty years after the discovery of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in 1983, we are witnessing unprecedented visibility of LGBT themes in mass media and in popular culture. Not surprisingly, Logo, the LGBT-themed cable network, which launched in 2005 (owned by Viacom, Inc.), recently announced its plan to de-queer the channel. Lisa Sherman, Logo's Executive Vice-President, told the Washington Blade (March 1, 2012): “...Culturally, we’re past the tipping point. For gays and lesbians, it’s part of who they are, but they don’t lead with it, because many are leading fully integrated, mainstream lives... Our goal at Logo has always been to honestly reflect our viewers’ lives. We’re now reinforcing our commitment to them with programming that truly mirrors how many of them are living and want to be entertained today.”

Logo’s decision was made largely because LGBT themes are increasingly part of mainstream shows. According to Logo's market research LGBT people no longer want to be ghettoized in their social spaces, neighborhoods, and in their consumption of culture. But, who can opt out of the ghetto and who can’t?

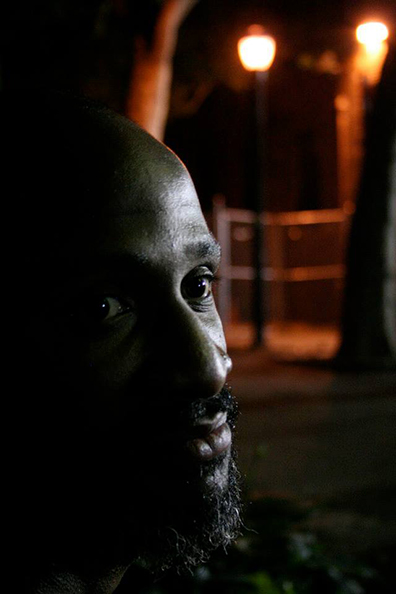

Zachary, 2013, Ted Kerr

Many people assume that the HIV epidemic in the U.S. has been contained, which in some respects is an accurate statement, but not in ways that should keep us calm. While the overall number of annual HIV infections has remained fairly stable for the last twenty years, nearly the total share of those infections has been taking place within spe-cific communities. HIV has become ghettoized to primarily circulate amongst poor black gay and bisexual men, black transgender women, poor black women, the homeless, and drug users.

When you think about the manner in which AIDS activism and organizing facilitated a range of policy wins for LGBT people–but in particular for white gay men, a demograph-ic that had a dramatic reduction in mortality and morbidity from AIDS since the introduc-tion of antiretroviral therapy treatments in the late 1990s–it is interesting to note that many of the organizations that were founded in the 1980s and 90s to counter homophobia, like the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) for example, have entirely abandoned AIDS as an issue to mobilize around. Former ACT-UP NY member and co-founder of Treatment Action Group (TAG) Peter Staley noted as much in a 2013 GLAAD Award acceptance speech noting, “the AIDS activism that led to the breakthrough treatments in 1996 stands as the proudest achievement the gay popu-lation of this world can every claim. But let's face it. A lot of us walked away from the fight after the drugs came out. Given the overwhelming fatigue we all felt after 15 years of unrelenting death, wanting to put this behind us was understandable. But the AIDS crisis didn't end.”

A forceful tide of research has been taking place for fifteen years pointing out the racial disparities in new HIV infections, but the response to that tide has been, arguably, inad-equate. These rates aren’t shocking to anyone working in the HIV/AIDS field anymore. But when I talk to people who don’t work in the field, for instance, that young black gay men in Atlanta, Georgia have one of the highest figures for HIV incidence ever recorded in a population in the resource-rich world, there are audible gasps. Despite the fact that HIV treatments are more effective and better than they were even a decade ago, I am still losing HIV-positive friends, some to AIDS itself, and others to suicide and drug overdoses. The two latter are often due to the depression and isolation that an HIV-positive status may bring. Although we often highlight how poverty and social isolation are associated with higher rates of HIV, I often wonder if, for the ten or so Black and Puerto Rican gay friends I’ve lost in the last four years, their roles as leaders in the community actually helped fuel their sense of isolation, depression, and in some cases their need to carry their HIV di-agnosis to their early grave. All of them were activists, artists, community organizers. Several ran organizations. All were under the age of forty three. At times like this, I find myself in Essex Hemphill's position: "When my brother fell I picked up his weapons.”

In between memorial services, new epidemiological studies are released every couple of years showing the increasing rates of HIV infection among Black gay and bisexual men, and yet responses are virtually the same: Conference calls with community leaders are organized and consultations of community activists with federal agencies like the Cen-ters for Desease Control (CDC), the Office of National AIDS Policy (ONAP), or the De-partment of Health and Human Services (DHHS) take place, to demand an explanation to the statistics, and heightened attention to the health crisis, and some policy recom-mendations and program funding initiatives. These conversations are often uncomforta-ble, but generally that is where they end, until the next study is released and everybody falls back into their predictable roles. Working meetings at expensive hotels are not what Essex Hemphill had in mind. He rejected fairly passive acts, like needles and threads, quilts and ribbons, meetings and conference calls.

Charles, 2013, Ted Kerr

I often feel very lucky and sometimes very alone. I work in Washington D.C. as Policy Director for Treatment Action Group (TAG) in a post that is ostensibly like most policy jobs: I participate in meetings with federal agencies, partner organizations and Hill staff-ers to try to save the ridiculously low amounts of government money allocated for healthcare, food, housing and education issues. I often have to make an argument as to why these basic human needs should actually be funded with tax dollars. As enraging as I find this process, it has also brought me more clarity around why we continue to lose. When I work with the AIDS community in D.C., I understand why the official level of “ad-vocacy” is important but also why it is entirely inadequate: To believe that lobbying and political strategizing are the only plausible avenues for social change, one has to believe other parties actually care whether a certain community lives or dies. If one assumes they don’t care, it forces one to raise the stakes for what needs to be done to get what a community needs. Luckily in my short tenure so far I’ve found support at TAG to take sometimes unpopular positions on policy and research issues, and I have the opportuni-ty to shift how to engage policy work that’s more about broader stakeholder engage-ment. Let us remember that the work of engaging federal, state or city agencies does not happen without the engagement of a grassroots constituencies.

I didn’t question whether I could aim or be as precise as he.

My decade-long work as an organizer working on local grassroots campaigns was not perfect but at least it had at the core the question: How do we build power? Power is not built by a selected elite in leadership roles. Power is built by truly assisting people to become leaders in their own right and to respond to whatever conditions may come their way. Policy change has happened because at the base were community folks who organized and worked on political education. Policy change should occur in the context of organizing a base constituency. When this doesn’t happen, efforts by advocates to change policy rarely have lasting impact.

Aldrin, 2013, Ted Kerr

An advocacy model where select “leaders” get to meet with institutions of power to shape public policy does not work. With the exception of money, power only responds to the ability to mobilize a mass base. Community organizing gives ordinary people the ability to demonstrate against discrimination and oppression, to envision a different set of political possibilities, and potentially to influence public discourse. But when legislation passes for example, it can be unenforced or undone if policymakers know that you don’t have a larger base of support that will respond to that shift.

Surprisingly, this top-down model of advocacy is being actively promoted and adopted by a younger generation of black gay men, despite their earnest interest in being of service to the community. So it’s not uncommon to hear many younger Black gay HIV advocates reference and promote the great legacies of Essex Hemphill, Bayard Rustin, Marlon Riggs and others by referencing them on social media or at public events, but studying or embodying their political commitments and ethics to social justice agendas that involve radical cultural and political strategies is not reflected in the work of many of these new activists and organizations. There are only a handful of organizations invested in developing new models for community organizing, base-building, political education, movement-building, and in developing grassroots leadership among black gay men who aren’t in universities, bound for graduate school, or working as a part of the AIDS, Inc. machinery. This is partly due to a number of things that have happened over the last twenty years, including the abandonment of LGBT funding for HIV/AIDS as a social justice issue and the lack of support for local (non-national) community organizations. Consequently, black gay cultural and organizing groups have shifted to become government funded HIV prevention organizations, which has lead to an overall invisibility of HIV as a social justice issue amongst black communities within the United States. The fact that even these organizations are closing or have seen their impact dwindle even further is evidence that a different approach is needed.

HIV/AIDS community activists, black gay men or otherwise, have to be willing to really ask ourselves, what are we willing to risk to end the epidemic? Are we too comfortable in our professional jobs? Are we too enamored by the social capital we have gained by being invited to important meetings by government officials? Are we seduced by the nice hotels, the meals and by posting selfies with members of Congress? Are we willing to organize, agitate, and disrupt these very spaces we seem to have gotten so comfortable in being a part of?

A needle and thread were not among his things I found.

Kenyon Farrow has been working as an organizer, communications strategist, and writer on issues at the intersection of HIV/AIDS, prisons, and homophobia.

***

There is Tremendous Ferocity in Being Gentle

Nathan Lee and Carlos Motta discuss PrEP and the blurring lines between positive and negative

It's a Wrap, Jess Mac, 2014

June 17, 2014

Dear Carlos,

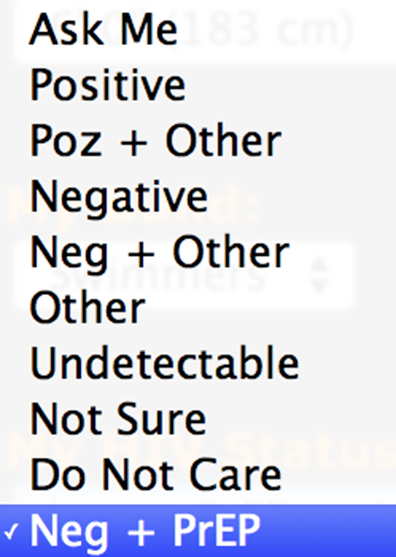

I’m glad we’re having this conversation about PrEP, and I’m glad it makes me uncomfortable. It should: Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis is a perfectly overdetermined object of consternation, a jagged little pill to drive everyone crazy. PrEP triggers anxieties about sex and sexuality, economics and access, moralism and shame, self-determination and the well being of communities. There are no answers with PrEP, only the mobilization of problematics.

Two of these are of particular interest to me: The first issue is the fact that men who have sex with men enjoy doing so without condoms, and how this quite understandable desire has undergone extraordinary complications since the advent of HIV/AIDS. PrEP reminds us that the introduction of condoms into queer sex is an extremely recent phenomenon, as well as how profoundly the AIDS crisis has shaped the practice, discourse, and ethics of our sexuality. PrEP has the curious effect of being a highly artificial means to protect people from the effects of “natural” sex, which is to say it participates in a project of denaturalizing sex whose genealogy passes through feminism and birth control, queer theory and ACT UP, the mainstreaming of LGBT representation and the rise of transgender activism.

The second problem that interests me is the nature of the human-pharmaceutical machine inaugurated by PrEP. I think it’s reductive to condemn PrEP on the one hand as the latest, most insidious penetration of Big Pharma into our lives; it is, after all, the direct result of the work of AIDS activism during the crisis years to develop effective drugs to combat HIV. On the other hand, however, there are dangers to embracing it as a fabulous twist in better living through chemistry, the slutty buddy to our daily multi-vitamin.

I’ve put a lot on the table to get us started, so let me backtrack a bit to clarify the stakes of this conversation. We both take Truvada. You recently started a PrEP regimen as part of a behavioral study; I’ve been taking Truvada (along with Reyataz and Norvir) since 2008 to treat my HIV infection. PrEP, then, is something “outside” me, just as HIV positivity is something “outside” you. I’m interested in how this difference affects our practices and our thinking, but also the ways in which the future of our bodies remain indeterminable, open ended, the site of conflicts, questions, experiments.

Why did you start taking PrEP, and how do you

feel about it?

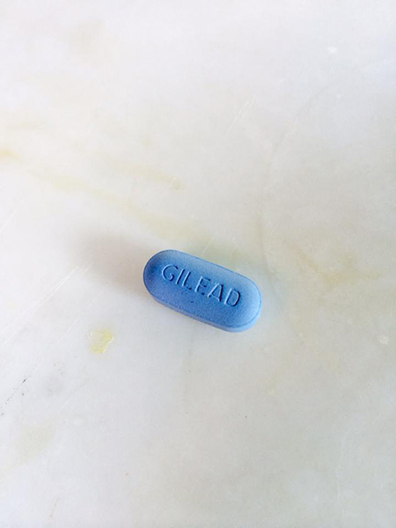

Magical Pill, Carlos Motta, 2014

June 25, 2014

Dear Nathan,

I have been on PrEP for four months and have been dealing with a wide range of culturally imposed “side effects.” My decision to take Truvada was motivated by wanting to be part of a research study named SPARK, co-offered by the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center and Hunter College, which seeks to observe the ways in which Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis as prevention influences sexual behaviors and risky decision-making regarding safer sex practices. I was drawn to the study for a variety of reasons, which are both intellectual and carnal: I am 36-years-old and my relationship to sex has, since my adolescence, been marked by a huge fear of HIV/AIDS. I am part of a generation of gay men who could only envision having sex with condoms and who were brought up under the shadow of a health crisis that had wiped out almost a whole generation and that continued to threaten us. Gay sex to me, for many years has equaled the risk of infection, something that has made it scary albeit infinitely desirable yet ineffably conditioned and determined by cultural and social politics. At the same time, it would be hypocritical of me to deny, as you mentioned above, the irrational desire I have always had to have unprotected sex and how that desire conflicts with all the medical, cultural and political constructs around HIV infection. PrEP, as you suggest, triggers so many anxieties and poses so many problems that make evident deeply rooted systemic inequalities and the construction of personal and social “freedoms.”

Having this conversation doesn't make me uncomfortable (although I am aware it stems from my own privilege as someone that has access and is willingly using preventive HIV medication); in fact I crave having open conversations on and about HIV and PrEP that are not pre-determined by:

1) Constricting agendas

of condemning moralism and stigma.

2) “Radical” critiques

that reproduce reductive discourses and unnuanced social ideas of social

justice.

3) Nostalgic invocations

of previous (heroic) HIV/AIDS activism and prevention strategies.

4) Short-sighted

rhetoric that encourages conflicts and divisions amongst the infected and

uninfected.

How could we move and look ahead to take on the many challenges, benefits and problems posed by PrEP in a way that is historically informed, socially aware and medically responsible yet respectful of personal and collective choices?

The rise of the “Truvada

Whore” rhetoric around PrEP is, in my opinion, an example that conflates

these four concerns. The assumption that Truvada is only a recreational drug that enables gay promiscuity and turns its

back to the two-decade history of HIV/AIDS activism and prevention is myopic at

best. The framing of this rhetoric (which has been appropriated by conservative

and progressive critics) stems from a déjá vu moralism that still deems

monogamous sexual relations as respectable and condemns sex with multiple

partners as a hedonistic and irresponsible behavior. It has been interesting to

observe the predictable ways in which the “whores” have been yet again exposed,

stigmatized, feminized, ridiculed and made an object of public shame. These “whores”

(poppers sniffers, fist fuckers, barebackers) ostensibly have no agency and

resurrect from the gay sexual fringes to stall social progress. But there’s so

much more at stake here and so many different perspectives that resist these

forces. PrEP suggests a directional movement that needs to be followed and tested

because it may change society’s relationship to HIV/AIDS. What are your

thoughts on this?

Nathan Lee, 2014

July 5, 2014

Hi Carlos,

Let’s look a little closer at this strange phrase “Truvada Whore.” Once again, as you noted, we’re facing another of these tiresome debates about promiscuity in relation to gay sex and HIV/AIDS. I’m reminded of positions staked out in the early years of the AIDS crisis. On the one hand you have people like Douglas Crimp arguing on behalf of promiscuity as a survival strategy, and on the other hand someone like Larry Kramer thundering against the selfishness of sexual entitlement. It’s easy enough to valorize Crimp’s proposal as a radical technique of the self, and to demonize Kramer’s position for aligning with a normative politics of assimilation. I’ll admit to finding Kramer’s hectoring–most recently in relation to PrEP–obnoxious at best. There’s something deeply phobic and mean-spirited about his demagoguery, a toxic mix of moralism and sex panic. None of this is to discredit in the least the power his apocalyptic absolutism had on mobilizing HIV activism. I don’t mean to single out Kramer as the problem; he is only the most audible (and quotable) voice in our community expressing anxiety about the politics of promiscuity.

Why shouldn’t we be whores? Why not fuck as many people as we want however we want? We can and should take these questions seriously; one of the enduring legacies of queer theory and activism during the AIDS epidemic was to articulate promiscuity as a concept, and to experiment with how to deploy that concept in life. But of course the question of why we shouldn’t fuck however we want got a really fucking intense answer with HIV. The danger in the ethos of absolute sexual self-determination is that it’s a fantasy; we construct our practices within cultural, political, and ecological frameworks. One of the most provocative claims in Tim Dean’s remarkable book on bareback subculture, Unlimited Intimacy (Chicago, 2009), is that barebacking can be understood not as the disavowal of the strategies developed to cope with the AIDS crisis, but as their direct evolution, “the next logical step in the enterprise of gay promiscuity.” I think he’s right about that, but I also think that his strategic de-emphasis on the role of antiretroviral therapy creates a blind spot in his critique. The enterprise of barebacking, and PrEP, cannot be abstracted from the logic of neoliberalism and multinational capitalism.

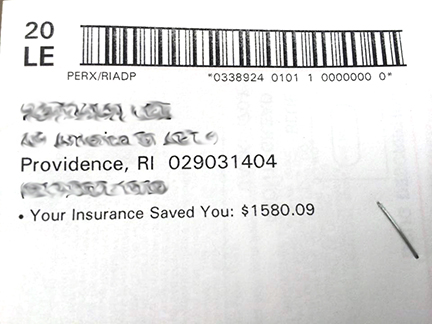

Which brings me to the Truvada in “Truvada

Whore.” Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis sounds deceptively neutral. PrEP is not a

generic category of treatment; it is the use of a single, extremely expensive,

trademarked product (Truvada) produced by a particular coorporation (Gilead)

with a current market capitalization of $134 billion. This is part of what

makes me uncomfortable talking about PrEP. I believe in defending it. I think

we need it. I want all kinds of people to benefit from it: Sluts and

barebackers, serodiscordant couples and sex workers, the privileged and the

precarious, the insured and the uninsured. And yet I’ve recently given myself a

thought experiment: what would it mean for everyone to be on Truvada?

What would happen if Gilead made it free and the entire population of Brooklyn

or Nairobi or London or Sí£o Paulo started taking it? It’s a terrifying idea.

Needless to say the logic of PrEP is such that it will never be free or widely

available. I get Truvada for “free” because I make less than $40,000 a year and

so qualify for government assistance. Some amount of the cost, however, about

$1500 a month, is picked up by taxpayers who subsidize the program, to say

nothing of the entire operation required for me to pick up a bottle once a

month: The caseworker who enrolled me in the drug-assistance program, the nurse

who draws my blood a few times a year, the lab technician who analyzes the

sample, the doctor that evaluates the results, the pharmacist who fills the

prescription, the cashier who processes my order. Resisting PrEP on the grounds

that it implicates one in corporate profiteering is naíve and reductive. But

ignoring the networks it connects us to, and failing to question their

protocols, is a bigger ethical failure than being a whore.

July 6,

2014

Hi Nathan,

Ignoring those networks, in my opinion, is a form of complacency that implicates us with the workings of a greedy capitalist system that favors financial gain over human life and that reproduces systems of geopolitical and cultural privilege. Gilead should not only drop the price to make Truvada available to more people, but it should also drop the patent altogether so that the pill can be part of a competitive market and become more accessible at reasonable prices. There is no doubt that the economics around PrEP are as fucked up as any other market-based product within (and beyond) the pharmaceutical industry. But labeling the inability to see these fucked up systems a “a bigger ethical failure than being a whore,” however, reproduces a binary that I refuse to endorse: On the one end of the binary the “big” issues of politics, economics, class, etc. and on the other end the “lesser” issues of the body, sex and affects. I constantly find myself in the annoying position to have to remind leftist activist and thinkers (from members of the Occupy Movement, to participants in high profile international conferences, to direct action activists) that sexuality and gender are not “lesser” issues to class struggle or economic inequality and that their rhetoric of revolution is often sexist and homo and transphobic.

If an equivalent treatment to PrEP were available to prevent cancer for example, would those seeking treatment ever be called “whores”? Is cancer prevention a more “ethical” project than HIV/AIDS prevention? I insist on highlighting the ways in which moralistic (not ethical) discourses around HIV infection continue to be tainted by the judgment, fear and condemnation of sex acts (both homo and heterosexual), something that over determines social hierarchies. It has been interesting to see the ways in which queer communities have split around PrEP: Both radical activists seeking to bring forth an economic critique of the treatment and mainstream gays unbothered with their own privilege, coincide in their use of “whore” as a category that ultimately demonizes sex as private stripping it from its public, social and political connotations. An economic critique would also need to be powered by a systemic critique that intersects “bigger” and “lesser” issues. I think only then we can produce nuanced positions around the web of problems exposed by PrEP.

Something else that I

am interested in is the ways in which PrEP has created a split between 1980-90s

(ACT UP) activists and a younger contemporary generation that think of HIV on

very different terms. How do you think the hard won discourse and action of the

“first” generation of activists (Kramer et al) is being defied by the PrEP

generation?

HIV* Medicine Options, Carlos Motta, 2014

July 13, 2014

Hi Carlos,

Your point is well taken about refusing to categorize issues as “bigger” and “lesser” since they are, as you observe, part of the same problematic. I should clarify that my comment was motivated by sarcasm. I don’t think being a “whore” is any kind of failure whatsoever in part because a person can’t be a whore, only judged one (by others or themselves). A whore is not a thing possessing an ethical dimension capable of failing or succeeding, whatever that could possibly mean; it is a moral enunciation, an act of valuation, a form of disapproval or affirmation. So much name-calling! So much finger pointing!

You ask me how the PrEP generation is defying the “first” generation of AIDS activists. I don’t think we’re defying anything; I think we’re trying to negotiate our own sexual, political, affective, and cultural landscape as best we can, and those landscapes are radically different than they were ten and twenty years ago. Could we be doing a “better” job? Of course. We all could. But that’s another thing that I’m hesitant to label bigger, better, worse, lesser: The ways a generation is trying to make their way in the world, the problems they’re confronting, the conditions they have inherited as well as the ones they perpetuate.

I recently ran into a well-known

writer and activist from the “first