I was able to study thanks to my work as a prostitute; I was able to collaborate with my family thanks to my work as a prostitute; I have what I have thanks to my work as a prostitute; I am who I am thanks to my work as a prostitute... then, is prostitution a dignifying work or isn’t it?

Diana Navarro

Download interview in PDF format ![]()

Descargue el texto en formato PDF en español ![]()

Descargue el archivo de audio (mp4) ![]()

An Interview with Diana Navarro

March 15, 2010

Option for the Right to Do and the Duty to Do Corporation,

Bogotá, Colombia

Diana Navarro at La Corporación

Diana Navarro: We are in Bogotá, in the locality of Los Mártires, my name is Diana Navarro San Juan, I am thirty-seven years old, and I am the Director of the Corporación Opción por el Derecho de Hacer y el Deber de Hacer. I am a well-known transgender person in Bogotá. My work began not only as a result of my sexual orientation or my gender identity; what was a determining factor for my work was the practice of prostitution. There I was able to get in touch with a different reality. At present I form part of the Women’s Advisory Council, the LGBT District Advisory Council, and the Social Politics and Territorial Planning Councils.

Carlos Motta: What kind of work does the Corporación carry out?

DN: At the Corporación we develop all sorts of affirmative actions aimed at achieving the restoration of the rights of persons practicing prostitution, or activities associated to prostitution, and of Bogotá’s transgender population, particularly transvestites, transformists and transsexuals. We have somewhat excluded intersex people and we have focused our work on the three mentioned groups because intersex persons, besides having made some jurisprudential and legislative progress, and despite the rulings of the Colombian Constitutional Court, deserve a different type of attention and we feel that if we include them within the transgender category, as it is done here in Colombia, we are rendering them invisible and concealing a large part of their problems.

CM: Could you tell me about what you do at the Corporación? What are the issues you address and what work are you carrying out?

DN: We do a lot of work on political incidence. We participate in local committees working on the formulation of both district and local public policies for the development and implementation of actions, the organization of the population’s participation, the categorization of existing groups.

Map of Los Mártires, Bogotá

CM: How did the Corporación originate?

DN: The Corporación Opción came into being as a result of a problem that occurred in Bogotá in 2001: a citizen lodged a writ of amparo ordering the then City Mayor, Antanas Mockus, to regulate or define exclusive zones for the practice of prostitution, which were then called tolerance zones. I was invited to participate because I had already implemented several actions, I had started to teach my workmates that they were not delinquents, that they had every right to carry out their work, that they had to do so in decent conditions, that neither the police nor any other stakeholders had any right to exert violence against them or hurt them, and this applied not only to my trans workmates but also to heterosexual and biological women. I attended a meeting in which a misinterpreted writ of amparo was being discussed. They said that according to that ruling, they could expel everyone from the locality of Los Mártires, and I declared myself against that decision. I filed a lawsuit. I studied Law at the University of Antioquia; I am the only transvestite in Los Mártires who has studied at a Colombian university. So I submitted to my workmates all the documentation we had and they named me their representative. That was the origin of the Corporación Opción. We did not become a legal entity until 2008, but we have been working since July of 2001.

CM: What was the situation that transgender or heterosexual women experienced at work?

DN: There weren’t any kind of guarantees, anyone could do whatever they pleased with us, mainly the police authorities, because they could infringe our rights, ignore our rights as valid social actors. Before the 1991 Constitution, Colombia was a Roman Catholic Apostolic country consecrated to the Holy Heart of Jesus. As of the 1991 Constitution, which really began to function in 1993, we became a secular State, the Concordat was broken, but the Church continued to do what it does with everything it does not consider normal, adequate, moral. Colombian education is permeated by many of those moralisms derived from Judeo-Christianism. The perspective regarding prostitution has been an abolitionist one, as in many countries of the world; it is a question of not warranting rights; it was a situation of persecution, imprisonment, the free exercise of these activities was not allowed. In 2002, we obtained the regulation of the only high-impact zone related to the practice of prostitution in Latin America. I wrote the regulations, they were approved, and on 2 May, 2002 the set of rules for La Sabana Planning Zone Unit (UPZ) saw the light, and it was decreed that normative sector 22 of the UPZ was a zone in which prostitution was allowed.

CM: This is, therefore, a consequence of the changes in the Constitution and of the work of the Corporación?

DN: Exactly. By appropriating all the constitutional changes, all the jurisprudential elements we could lay hands on, we achieved the establishment of the first high-impact zone for use referred to prostitution in the whole of Latin America.

CM: Does this imply the practice of prostitution in the street, or are there premises assigned for this purpose?

DN: In the street, in premises, in this sector you can practice prostitution anywhere you want.

CM: And what happens if someone abuses a person working in that zone, whether emotionally or physically?

DN: We have legal actions, we have already initiated disciplinary and administrative processes against government officials, or criminal processes against other persons. We now have tools to defend ourselves, because in Colombia, prostitution is in a state of juridical limbo. It is not legal, but it is not illegal, either. The Colombian Constitution makes reference to the right to free choice of profession and employment. Despite its being an economic activity, the second economic activity at world level in terms of generation of income, prostitution is not recognized in this country or in many other countries in Latin America, as what it is; on the contrary, it is considered a social problem. The International Labor Organization has an abolitionist perspective regarding prostitution because it states that its practice does not ennoble a person. I posed a question to an ILO official: I presented him my own example: I was able to study thanks to my work as a prostitute ; I was able to collaborate with my family thanks to my work as a prostitute; I have what I have thanks to my work as a prostitute; I am who I am thanks to my work as a prostitute...then, is prostitution a dignifying work or isn’t it? Moralism is derived from the fact that we do not use the body parts that other people normally use for the practice of this work; we use our genitals. We are still tied to those Judeo-Christian concepts that refer to the morality of sex and all the abolition of pleasure for the human being.

Description of the Corporación from a fundraising blog

CM: What is the status of the practice of prostitution outside the zone that has been assigned to you?

DN: It is difficult, in spite of the fact that Decree 4002 of 2004 establishes that there is a period for relocation, now we find ourselves in a limbo because District Planning determined they would not declare any more zones as high-impact zones. Only this zone, which is small, would be left to host all the establishments — which are more than 1500 — in which prostitution is practiced. More than 20,000 persons practice prostitution in this area. There is an inter-institutional work table which includes all the Government sectors in Bogotá, but in which the persons who practice prostitution are absent. Our voice has not been heard; work continues to be carried out for us, allegedly in our favor, but without us.

CM: Has the establishment of these zones led to the existence of less cases of abuse, ill treatment and discrimination?

DN: Yes, impunity has decreased and so have other things. It is a negligible decrease, but it is a step forward. The number of murders is not the same as it used to be; the criminal activities around the area have decreased. It is normal for delinquents to try to appropriate or take advantage of the spaces that offer services of entertainment or recreation for adults. But we are the first locality in Bogotá with a sizable decrease in criminal behaviors.

CM: What were, and are, those criminal activities?

DN: They range from murder to the sale of illegal psychoactive substances.

CM: Do you have any records of hate crimes or discrimination on grounds of gender identity and sexual orientation?

DN: Yes. We could witness this kind of thing the past year, in the case of the murder of two workmates by a group which wants to appropriate the micro-trafficking of drugs. They were displaced and murdered because they were trans persons; they seek to “normalize the territory”. Any person who is contrary to their requirements or the rules they are trying to impose in an illegal way is murdered or expelled. I myself am currently under threat from these groups.

CM: Are you under threat because you are a trans person or because you have occupied a zone that someone wants to use for another activity?

DN: I am under threat because based on my transgender identity I have succeeded in conquering spaces, I have managed to participate in many ambits; people listen to me; I have conquered a good will, to call it something. I am District consultant for LGBT and prostitution issues; people come to me to lodge denouncements, to report irregular behaviors that are taking place and they think that because I am a transgender person I have less rights, or I have no right to do the work I do. How has he managed to do all this, how is he doing all this if, like they say, he is a fag?

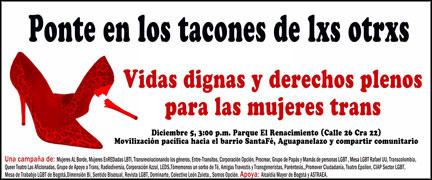

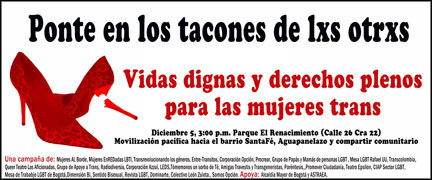

Flyer for a Trans Women Right's support march

CM: Does the Corporación have a categorical definition of being transgender?

DN: We depend on self-definition, on self-determination, on the person’s self-construction. If you come with a beard and a mustache, wearing a suite and you tell me you are a trans person, for the Corporación you are a trans person. Many of us express our gender in vehement ways, but others prefer to consider themselves, construct themselves, act in a certain way but have a contrary gender. That is what the queer is trying to reformulate. The queer theory rejects the binary element in gender, it rejects stereotypes and categorizations, and we very much agree with that. Charlotte Ezneda Callejas, whose legal name is Carlos Alejandro Díaz, is Cuban; she works in the Secretariat for Health as referent in issues regarding LGBT policies and when they ask me about her they ask about Luis Alejandro and I tell them “And who is that?” “The Cuban.” “Ah, Charlotte!” I always call her Charlotte because that is her identity construction, because that is her wish, and when I see her I call her Charlotte, even though that day she may have come disguised as a man. For me she will always be what she wants to be. There are gentlemen who come to seek advice; we call them closet trans and they come to see how they can construct themselves in a better way, how they can express the gender they wish to have. From the moment I cross that door, I call them whatever name they want to be called.

CM: I have just come from Norway, where as a political strategy, transgender persons want to make a complete transition, undergo surgery and legally change their gender in order to be protected by the law in a different way. This is a strategy to manipulate society’s codes and obtain rights. What do you think about that?

DN: It is a totally valid strategy, but here in Colombia we are totally screwed by Act 100. Under Act 100, all those processes of sexual reassignment or body transformation are considered aesthetic procedures and they are not covered by the Social Security. Regarding that, all processes are blocked, and now, with all those decrees on social emergency, it is even worse because we had managed to get some doctors to offer the possibility of a hormone treatment for persons who want to go ahead with that transit up to the point they want to reach. Not all transgender persons want to be sexually reassigned; it is valid to appropriate a number of things from that categorization in a positive way, but here in Colombia, the authorities use this in a negative way. We participated in the campaign against the pathologization of transsexuality and we had internal debates within the group because many workmates considered that if we were considered sick persons they would have to cure us, we could have access to treatments because we were affected by gender dysphoria and I said to them: it is a misunderstanding, because what they will cure is that psychological incongruence you have with your anatomical sex, so that you may feel comfortable with your biological sex, not for you to obtain the gender you wish to belong to. Colombia’s Political Constitution offers us a wide spectrum of possibilities; we can appropriate a number of things: health is a constitutional right, and so is a dignified life and the free development of one’s personality. In terms of legislative advancements, Colombia is in the vanguard, but in terms of recognition, of the establishment of actions that may lead to people being able to exercise all those constitutional rights in an appropriate way, we are fried.

CM: Are those constitutional rights not reflected in the street?

DN: They are not reflected in reality, and now that the U Party and the Conservative Party have won, it’s even worse.

CM: But are they reflected in Government institutions, that is, in the health system?

DN: No.

CM: What are the rights of transgender persons in Colombia?

DN: The right to dress as a woman if I want to and to dress as a man if I want to, that’s all.

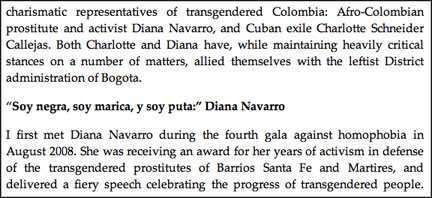

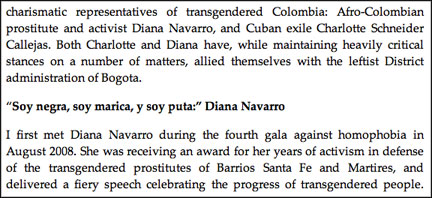

Excerpt of a text about Diana by Rachel Godfrey in The Panama News

CM: And if I shout at you in the street or I hit you, do you have the possibility to sue me?

DN: The Colombian Code of Criminal Procedure incorporates an aggravating circumstance under Article 58 # 3, referred to discrimination on grounds of sexual or gender orientation. In Colombia we haven’t made much progress in this respect, either. The general idea is that my gender depends on my biological sex, and we have not de-constructed that concept. The attorneys and the authorities of the courts of first instance that examine the processes do not record the motivation for this aggression. If I hit you and cause you an injury, I can be arrested if you make a formal complaint for personal injuries, but not on grounds of your being a man, a woman, a gay, lesbian, transgender or bisexual person; that remains invisible even though it may have been the latent motive. That is what I am demanding from the social movement, the appropriation of those tools, demanding that everything you say in a public hearing, in a denunciation, should be recorded; I ask this of my workmates: explain things properly, don’t just say “the guy hit me”.

CM: Does the work of the Corporación include community orientation?

DN: We have made great progress in this respect. In Bogotá we already have a district network of trans persons that we are empowering, strengthening, and we are offering them tools. The past year I had the chance to execute a project in the framework of the strengthening of social organizations for the IDEPAC, the goal of which was to create the district network of trans people. Based on that network, we finally have incidence on projects. We have already embarked on a project of visibilization and training in human rights for people to be trainers of trainers, for people to create their own tools, from a qualitative and a quantitative point of view, to compile all that information. We are going to hold a number of festivals, a number of inter local and district events. At the national level, we have already dynamized the processes in the coffee axis, we succeeded in sitting a Government Secretary with us and committing him to the population; in Popayán we did that fifteen days ago and we are planning to do the same thing in eight more cities. We will do so with funding we receive from a Dutch foundation called Mama Cash.

CM: You lead me on to the next question. Is there a work network at the national or regional level in relation to these issues?

DN: We are just beginning. We have worked intensely, but on sexual orientation. I say this colloquially: it was much easier to work among ourselves when in Colombia they only called us fags and dikes. But when we started using the acronym LGBT, which we use incorrectly because we shortened it, we categorized ourselves, we created divisions among the groups. In organizational and participative processes and the like, lesbians are stronger because they have had access to many things. Although they began with all these processes, gay persons lagged behind. Bisexuals are still very much hidden. It is much easier for a lesbian, a gay, a bisexual to go unnoticed or to be in hiding, like I say, than for a transgender person. We are not interested in going unnoticed, we are interested in being recognized in our full dimension. When you apply for a job, they don’t ask you what your sexual orientation is.

CM: Do they ask you about your gender?

DN: No, as a matter of fact you apply and they take it for granted that this is a man, he dresses as a man, he has short hair, he is a heterosexual male. They take that for granted, that you are heterosexual.

CM: And if a person dressed like you arrives, what happens?

DN: I have done that exercise many times and I have done it in one of the two areas in which we have the greatest possibilities. We called 25 notices that were published in the newspaper and at the end, when I already had an appointment, I said: I am a transvestite, is there a problem with that? Oh, no, they answered, people are not used to that here and they hanged up. We are a laughing stock. When I presented myself at the University of Antioquía, the secretary of the Admissions Department called me and said: by mistake, the photo of a lady appeared on your form, we don’t know why, how can we correct that? I said “No lady, it’s me, I am a transvestite. Is there a problem with that? No, not at all, she said. We talked and I obtained a place at university.

Trans Rights March in Bogotá, 2009, photo by Bianca Bauer

http://www.flickr.com/photos/biancita/3673830458/in/photostream

CM: Do you have the possibility to change your name, to change your gender legally?

DN: We can change our name but not our gender.

CM: That means that officially you are Diana Navarro?

DN: I have not changed my name because I have a political position in this regard. What is the point of my name being Diana Navarro San Juan in my ID if the male gender variable is going to continue appearing? They are not recognizing me in my full dimension. I don’t think it is worthwhile. Many of my workmates feel attracted by that and they think it is a step forward, but I don’t consider it thus, I consider that the variable of sex must be eliminated from IDs. In the new IDs, in the billion ID quotas, it has already been eliminated, But in the old Ids, it still continues to appear, so we, the people who obtained their IDs before the year 2000 continue to have the same problem.

CM: The change in the IDs was due to this issue?

DN: No, it was because it was considered that population was too numerous and there were many numbers on IDs, you had a number on your ID, on your passport, in your judicial past, in your social security, there were thousands of numbers for everything. Then the agreement was reached that we should have a single number for personal identification, the NUIP, and we cannot continue to use the variable of sex, neither male nor female.

CM: Did you obtain benefits as a community?

DN: Exactly, an indirect benefit.

CM: Can you tell me about the situation in the social sphere, the restrooms and all those matters in which binary gender is predetermined?

DN: In some cases we have had problems, but in universities, in theaters or shopping centers we have already achieved that respect. There’s still a lot to do.

CM: Can you use any restroom you wish?

DN: Normally I use the women’s restroom. But in a cemetery where we were attending the cremation of the body of a workmate, my workmates asked if they could use the restroom and they tried to prevent their access to the women’s restroom; I had to stand up and tell them: No, sir, they go to the women’s restroom because they are trans women. When have you seen a woman urinate in a standing position? It’s a permanent fight, a constant fight; one cannot drop one’s guard ever, for any reason. Pedagogical processes must be constant. In this respect we have been careless; one thinks that because we have a public district policy for LGBT persons, everything is done. No, everything is still to be done; work at the national level is pending, because it’s not possible that there should be a public policy only in one city in Colombia.

CM: What is your relationship with Colombia Diversa and what work does Colombia Diversa carry out in favor of the trans community?

DN: All around the world, we trans women have triggered achievements through visibilization. The simple presence of a trans in a given space implies political resistance, but we have lagged behind. Colombia Diversa has made progress only in the case of same sex persons. I do not see any other aspect in which it may have transcended. It lacks articulation, respect at work, greater recognition of diversities, because there is still much discrimination within our groups.

CM: Are you in contact with the leaders of Colombia Diversa?

DN: In some spaces we participate jointly.

CM: Isn’t there a project for making progress jointly?

DN: No, there isn’t a real articulation; they submit reports; they compile the information. That is why we are beginning to implement some organizational work. Last year, the Corporación Opción executed a project with the sponsorship of Astraea for the organization of a national encounter of trans leaders and leaderesses which was attended by 23 trans men and women from all over the country, because trans men are still very much invisible.

CM: In the course of this interview you have repeatedly made reference to trans women and never to men. What is the situation of the community of trans men?

DN: Based on the diagnosis I made at the national and district level, I could conclude that trans men are in a situation that is as difficult as that of trans women, or even more difficult. We can become visible and we have an inherent resistance; the female gender is very strong, very rebellious, very hardworking. Trans men are in a completely disadvantageous situation, many of them have achieved a body transformation that facilitates their blending with the rest of the population, but they still have the same problems that we have: in the assignment of identity documents, in access to health services. We have begun to integrate trans men in our work because it is necessary that their voice, too, be heard.

CM: Are there any leaders among trans men?

DN: There are groups; there is a group of trans children and adolescents; we know some in Pasto, also in Cali and here in Bogotá there are others, but the movement has not had the necessary strength to render it visible yet. We are trying to get them to organize themselves, to carry out part of the organizing of trans persons, to fight for their own interests just like we had to do at the beginning.

CM: Therefore, there isn’t a relationship that is, let’s say, theoretical or aimed at the implementation of policies?

DN: Exactly, and as here public policies have taken care of fragmenting populations, there isn’t a real social articulation, and that leads to every person being concerned with their own small interests instead of practicing the solidarity that would be expected for the whole of Colombian society to have access to the exercise of their rights.

CM: A question regarding the representation of trans persons in the media and in the sphere of culture: what is that situation like at present by comparison with the past?

DN: There has been some progress, not much. There have been several moments; here we were presented on TV as the drag queen, caricaturesque, ridiculous, as clowns. We were only hairdressers, florists, seamstresses, make-up artists, with very caricaturesque and exaggerated attitudes. This also forms part of our group, but it is not the whole group. Then there was a change and those figures are not presented any more; now it’s the criminal, the delinquent. With the presentation of a soap opera, Los Reyes, our fellow trans activist Endy Cardeño began to build many imaginaries, not only the prostitute, the hair stylist, the seamstress, but a person who, in her interiority, can practice any profession. In the United States, Ru Paul has her own television program, but regrettably it doesn’t reach Colombia. Those spaces have contributed to prevent the media from caricaturizing us, from stereotyping us, and we have been able to make some progress in the deconstruction of those imaginaries. We still have all the way to go, because for instance, despite the fact that we have a trans person as research coordinator at the Humboldt Institute, many of the persons who have managed to emerge or be successful have forgotten those who have not had the same privilege.

CM: You lead me to pose a question that is of great interest to me: Colombia is in its essence a society divided by class and by the economic situation, and I suppose this must be a strong issue within your community. Is there unity with people who have access to economic means and education?

DN: No, unfortunately there is no unity. From early childhood we are sold the sophism that we must practice prostitution in order to obtain an important capital, get a sponsor, go to Europe where we can make a lot of money through the practice of prostitution. We begin to undergo surgeries, to buy houses, material assets, in the belief that this will guarantee our insertion in society. I obtain cooperation from heterosexual persons more easily than from trans persons who are economically stable at the moment.

CM: What happens with high-class trans people?Is there any communication?

DN: No. There is an exaggerated classism, and that is serious because we are doing our work with an outward orientation and very little with an inward one. I would dare say that the only two organizations that work along that double track, outward and inward in the trans sphere, are the Corporación Opción and Trans Colombia. We want The Other to respect us, to respect our rights; we want the State to guarantee the exercise of our rights, but our fellow trans don’t know what those rights are. The right to the free development of one’s personality, the right to have a decent life, the right to work, the right to have a decent house, but they are not only the fundamental rights; also the economic, social and cultural ones, all those rights. We must also have access to those rights, not only to the right to go anywhere and not be ill treated, ridiculed or attacked for being what we are; we have all the rights a human being has, all, and in that field we have made no progress yet.

CM: What is the next step? I am under the impression that we find ourselves in a situation that is a little basic yet.

DN: Yes, we are just beginning. We have an important tool, the public district policy that guarantees the rights of LGBT persons, but there is still a lot of work to be done before it can be implemented, before it can be taken to any corner of the capital. Based on the work we are carrying out, with the Diversity Department, we are recognized as having some rights, the right to work, the right to security, to life, to culture and to education. Participation has increased, but all our specificities have not been recognized yet, and it is very unlikely that they will be. We have begun to teach people the basics so that they can be more outright, defend themselves on their own, organize themselves, and defend not only their own rights but those of the whole group. We do not overlook political incidence due to the knowledge we have, due to the tools we have acquired, the name we have developed here in Bogotá, we do not neglect other spaces that formulate policies, because here a law, a decree, a norm dynamized many things.

CM: How does the Corporación obtain its funding?

DN: The Corporación Opción has had funding from Astraea United State’s Lesbian Corporation for Justice on two consecutive occasions. Thanks to those contributions we were able to develop a series of projects together with the District Institute for Community Action Participation of the IDEPAC, the result of which was the creation of the district network of trans persons. Mama Cash granted us 23,000 euros this year, which allowed us to buy equipment and this year we will be able to devote ourselves 188% to this work; since we do not need to worry about anything else.

CM: Is the national government completely disconnected from the work you are carrying out due to lack of interest in it?

DN: The national government is interested in co-opting the work of social organizations. Let me explain: we do the work, we implement a series of agreement tables and we sign a decree that is often incorrectly signed, we generate an incorrectly sanctioned policy and that is the government’s job. In terms of funding, there is no policy, President ílvaro Uribe even considers us delinquents because we make denouncements, we do not remain silent.

CM: Does this apply to transgender persons or to the persons who do the work?

DN: To us who practice prostitution, to transgender persons, to the LGBT. We participate in all the shadow reports, in all the visits from the United Nations High Commissioner and we denounce, we offer evidence of the processes that are unfinished. Because last year the United Nations requested a report on human rights from the Presidency, and they said: here everything is pretty, everything is beautiful, here they can get married, here we initiated the debate of a bill on the marriage of same-sex couples, here the Constitutional Court said this and this. No, sir; not everything is all right, not everything is beautiful. Look at so many murders, so many lawsuits with no rulings, so many missing persons, all this conflict. What bill? If it has been debated on four occasions and it has been defeated. What legislative progress? Here we cannot get married, we can only have recognition of our de facto marital union based on a ruling from the Constitutional Court. It wasn’t the Government, it was the Constitutional Court that pronounced a ruling putting those rights on a par with the rights for heterosexual persons, based on the right to the free development of one’s personality and the right to equality. Then we said: no, that is a lie.

CM: Do any of the presidential candidates address this issue, or nobody addresses it?

DN: Not really. Despite the fact that the alternative Polo Democrático, the political party of which I form part, has a positive discrimination quota for the political participation of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgenders, Gustavo Petro, the party’s official candidate, has not pronounced himself, he had an unfortunate meeting with some fellow trans, in which he said he assumed no commitments with anything, he simply wanted to listen.

CM: In a country that lives such a brutal atmosphere of political violence and social inequality as Colombia, will the issues involving gender identity not be perceived as an unimportant item in the agenda?

DN: Yes, unfortunately, because this does not involve only the fact that you sleep with another man, another woman, or a man and a woman, or that you want to dress like a man or like a woman. Minimizing the problem, it has been perceived in this way. We have no access to health, we have no services with a differential perspective that renders them adequate for our specificities and our needs; we haven´t got that. I was telling a senator: What the hell do I care about a right to the free development of personality if I have no access to medical care, I cannot transform my body to adapt it and be faithful to the feminine or masculine ideaI I aspire to, which is not a simple whim, which is not a simple invention, it is a need of mine, and a need that requires a psychological, medical, interdisciplinary accompaniment. I don’t have those differential services, I don’t have them. How am I going to develop my personality freely if I don’t have the right to health, if I don’t have the right to work because I dress like a woman being a man. How am I going to have the right to the free development of my personality if I do not have access to decent housing. I live like a queen because I live in an apartment in which the hygienic-sanitary conditions are adequate and which meets certain standards. But if we make a tour of the places where many workmates live, we’ll find that they live in rooms of 2 by 2 meters, in which a bed barely fits, with disgusting bathrooms in a awful conditions. Many of my workmates go to rental firms to rent an apartment and they are denied this service. In my case, because of the credit record I have had for years and because I have not wanted to change my name, I submit the form with my legal name.

CM: What is your legal name?

DN: William Enrique Navarro San Juan. With my legal name, with the financial background I have through my credit card, my savings account, of all the loans I have been granted, that I am still granted, with my credit background, I submit all the documentation without my being present; I send it through my secretary, or by mail, by any means, and the application is approved. Once it has been approved, when I appear, they have to hand me the keys, after a contract has been signed they can no longer do anything to you, but many of my fellow trans do not have that access, so they depend on third parties that even exploit them for them to be able to have access to somewhat decent living conditions.

CM: Diana, we are finishing this interview; tell me about issues of sexual health. Do you have any information on indices of AIDs and other health disorders?

DN: Simply not, sexual education and reproductive sexual health are not based simply on sexually transmitted infections or HIV-AIDS, but we have been categorized in such a way that they are diseases attributed exclusively to us. I arrive at the doctor’s with a pain in a nail and he asks me: Have you already taken the AIDS test?

CM: Not only the transgender community; homosexuals too...

DN: Of course! Have you already taken the AIDS test? Do you use a condom? As if the whole of the sexual and reproductive health issue boiled down to that. Here district reports by locality on the prevalence of HIV infection are presented annually, and the persons who practice prostitution are the ones with less prevalence. Not only because we are aware of the problem, but because we know that if we catch any disease we cannot continue to be productive. The year before last, when I took all those trips for the construction of the meeting and the formulation of the work proposal with trans persons, I told my workmates, teach me to put a condom on, and they didn’t know how to do it. Likewise, the use of lubricants is not included in these trainings; we are told we cannot use Vaseline, we are told we cannot use oil-based lubricants, but we are not told what we can use, nor do we have access to the lubricants. The national government thinks that by distributing condoms it will achieve that Millennium Development Goal. Sexual education classes do not work at school. They are pervaded by those Judeo-Christian moralisms I was telling you about. What they teach you at school is that you have a penis, a pair of testicles, and what they are used for, nothing more. They do not teach that there are possibilities of having sexual relations at an early age, that our sexual awakening takes place at the age of ten, that by the time we reach age fourteen we have the possibility to interact. We are not taught responsible sexuality; it is demonized. There are no real, conscious sex education classes that teach us all that gamut of possibilities, that teach us to respect our own bodies, to respect other persons’ bodies, how to obtain pleasure from our bodies without hurting ourselves, without hurting other people. There isn’t a sexual education class, they just tell you wear a condom, use a condom so that no infection is transmitted to you and so that you don’t die.

CM: Thank you very much and lots of luck with this. I think you are carrying out a titanic task.

Weblink: Option for the Right to Do and the Duty to Do Corporation

↑Top

Read edited transcript in English

Download interview in PDF format ![]()

Descargue el texto en formato PDF en español ![]()

Descargue el archivo de audio (mp4) ![]()

Pude estudiar gracias al ejercicio de la prostitución, pude colaborarle a mi familia gracias al ejercicio de la prostitución, tengo lo que tengo gracias al ejercicio de la prostitución, soy quien soy gracias al ejercicio de la prostitución, entonces ¿la prostitución dignifica o no dignifica?

Una entrevista con Diana Navarro

Marzo 15, 2010

Corporación Opción por el Derecho de Hacer y el Deber de Hacer, Bogotá, Colombia

Diana Navarro en la Corporación

Diana Navarro: Estamos en Bogotá, en la localidad de Los Mártires, mi nombre es Diana Navarro San Juan, tengo treinta y siete años, dirijo la Corporación Opción por el Derecho de Hacer y el Deber de Hacer. Soy una transgenerista reconocida en Bogotá. Mi trabajo no sólo empezó por mi orientación sexual o mi identidad de género, lo determinante en mi trabajo ha sido el ejercicio de la prostitución. Allí me he podido encontrar con otra realidad. Ahora hago parte del Consejo Consultivo de Mujeres, del Consejo Consultivo LGBT Distrital y de los Consejos de Política Social y de Planeación Territorial.

Carlos Motta: ¿Cuál es la labor de la Corporación?

DN: En la Corporación desarrollamos todo tipo de acciones afirmativas para la restauración de los derechos de las personas que ejercen la prostitución, actividades conexas a la prostitución y para la población transgenerista de Bogotá, en especial travestis, transformistas y transexuales. Hemos excluido un poco a las personas intersexuales y hemos focalizado nuestro trabajo en estos tres grupos porque las personas intersexuales aparte de tener algunos avances jurisprudenciales y legislativos, de los pronunciamientos de la Corte Constitucional Colombiana, merecen otro tipo de atención y sentimos que incluyéndolos dentro del transgenerismo, como lo hacen aquí en Colombia, los estamos invisibilizando y ocultando gran parte de su problemática.

CM: ¿Me podrías hablar acerca de lo que hacen ustedes en la Corporación? ¿Cuáles son los temas que tocan y cuál es el trabajo que están desarrollando?

DN: Hacemos mucha incidencia política. Participamos en comités locales para la formulación de políticas públicas, tanto distritales como locales, para el desarrollo e implementación de acciones, la organización de la población para la participación, la cualificación de los grupos que ya existen.

Mapa de Los Mártires, Bogotá

CM: ¿Cómo surge la Corporación?

DN: La Corporación Opción surge de un problema que hubo en Bogotá en 2001: un ciudadano colocó una acción de tutela ordenándole al Alcalde Mayor de ese entonces, Antanas Mockus, reglamentar o definir zonas exclusivas para el ejercicio de la prostitución, en ese entonces se llamaban zonas de tolerancia. Me invitaron a participar porque yo ya había hecho algunas acciones, les había empezado a enseñar a mis compañeras que no eran delincuentes, que tenían todo el derecho a ejercer su trabajo, que lo tenían que ejercer en condiciones dignas, que ni la policía ni otros actores podían violentarlas o vulnerarlas, no solamente a mis compañeras mujeres trans, sino a las mujeres heterosexuales y a las mujeres biológicas. Fui a una reunión en la que se debatía un fallo de tutela mal interpretado. Decían que al tenor de ese fallo podían expulsar a todo el mundo de la localidad de Los Mártires y yo me pronuncié en contra. Hice un pronunciamiento legal. Yo estudié derecho en la Universidad de Antioquia, soy la única travesti en Los Mártires que ha estudiado en la universidad en Colombia. Le presenté a mis compañeras todo lo que teníamos y ellas me nombraron desde ese entonces su representante. Ahí nació la Corporación Opción. No nos legalizamos hasta 2008, pero tenemos trabajo desde julio del 2001.

CM: ¿Cuál era la situación en el ámbito laboral que vivían las transgeneristas o las mujeres heterosexuales?

DN: No había ningún tipo de garantías, cualquiera podía hacer lo que quería con nosotras, principalmente las autoridades policiales podían vulnerarnos, desconocernos como actores sociales válidos. Antes de la Constitución de 1991 Colombia era un país Católico, Apostólico, Romano y consagrado al Sagrado Corazón de Jesús. A partir de la constitución del 91, que empezó a funcionar realmente en el 93, pasamos a ser un Estado laico, se rompió el Concordato, pero siguió eso que hace la iglesia con todo lo que no considera normal, adecuado, moral. La educación colombiana está permeada por muchos de esos moralismos derivados del judeocristianismo. La perspectiva sobre la prostitución, como en muchas países del mundo, ha sido abolicionista, se trata de no garantizar los derechos; era una situación de persecución, encarcelamientos, no se permitía un libre ejercicio. En 2002 logramos la reglamentación de la única zona de alto impacto con uso referido a la prostitución en América Latina. La redacté, la aprobaron y el 2 de mayo de 2002 salió a la luz la ficha reglamentaria de la UPZ de la sabana y se decretó que el sector normativo 22 de la UPZ era una zona en la que se permitían el ejercicio de la prostitución.

CM:¿Esto es entonces un producto de los cambios en la Constitución y de la labor de la Corporación?

DN: Exactamente. Apropiándonos de todos los cambios constitucionales, de todos los elementos jurisprudenciales de que pudimos, logramos la ubicación de la primera zona de alto impacto con uso referido a la prostitución en toda América Latina.

CM: ¿Esto significa el ejercicio de la prostitución en la calle, o son locales asignados para el ejercicio?

DN: En la calle, dentro de los locales, en este cuadrante puedes ejercer la prostitución donde quieras.

CM: Y si alguien abusa ya sea emocional o físicamente de alguien que está trabajando en esa zona ¿qué pasa?

DN: Tenemos acciones legales, ya hemos iniciado procesos disciplinarios y administrativos contra funcionarios o procesos penales contra otras personas. Ya tenemos herramientas para defendernos, porque la prostitución en Colombia está en un limbo jurídico. No es legal, pero tampoco es ilegal. La Constitución de Colombia habla de la libertad de elección de trabajo y oficio. La prostitución, pese que es una actividad económica, la segunda actividad económica en el mundo en generación de recursos, no está reconocida ni aquí ni en muchos países de América Latina como lo que es; se considera, al contrario, una problemática social. La OIT tiene una perspectiva abolicionista de la prostitución porque dice que su ejercicio no dignifica a la persona. Yo le hice una pregunta a un funcionario de la OIT: le puse mi ejemplo; pude estudiar gracias al ejercicio de la prostitución, pude colaborarle a mi familia gracias al ejercicio de la prostitución, tengo lo que tengo gracias al ejercicio de la prostitución, soy quien soy gracias al ejercicio de la prostitución, entonces ¿la prostitución dignifica o no dignifica?

El moralismo se deriva de que nosotras no usamos la parte corporal que normalmente usan otras personas para el ejercicio del trabajo; usamos nuestros genitales. Todavía estamos pendientes de estos conceptos judeocristianos que hablan de la moral del sexo y de toda la abolición del placer al ser humano.

Descripción de la Corporación en un blog de patrocinio

CM: ¿Cuál es la situación del ejercicio de la prostitución por fuera de la zona que les han asignado a ustedes?

DN: Es difícil; pese a que el Decreto 4002 del 2004 establece que hay un período para la reubicación, ahora nos encontramos en un limbo porque Planeación Distrital se pronunció diciendo que no iban a declarar más zonas de alto impacto. Quedaría únicamente esta zona, que es pequeña para acoger a todos los establecimientos, que son más de 1500, donde se ejerce prostitución. Más de 20.000 personas ejercen la prostitución aquí. Existe una mesa interinstitucional de trabajo en la que se encuentran todos los sectores gubernamentales de Bogotá, pero sin presencia de las personas que ejercemos la prostitución. No se ha escuchado nuestra voz; se sigue trabajando para nosotras, supuestamente por nosotras, pero sin nosotras.

CM: ¿El establecimiento de esta zona ha permitido que se registren menos casos de abuso y de maltrato y discriminación?

DN: Sí, disminuyó la impunidad y otras cosas. Es una disminución poco significativa, pero es un paso. Ya no ocurren esa cantidad de homicidios de antes, las actividades delictivas que circundaban la zona se han reducido. Es normal que el delincuente quiera apropiarse o aprovecharse de espacios donde hay servicios de entretenimiento o de recreación para adultos. Pero somos la primera localidad en Bogotá con una alta disminución de conductas delictivas en Bogotá.

CM: ¿Cuáles eran y son estas actividades delictivas?

DN: Desde el homicidio hasta la venta de sustancias psicoactivas ilegales.

CM: ¿Se registran también casos de crímenes de odio y discriminación por identidad de género y orientación sexual?

DN: Sí. Lo pudimos ver el año anterior, en el caso de dos homicidios de dos compañeras, por parte de un grupo que se quiere apropiar del micro tráfico de estupefacientes. Las desplazaron y asesinaron por ser personas trans; buscan “normalizar” el territorio. Toda persona contraria a sus requerimientos o a las reglas que tratan de imponer de manera ilegal, es asesinada, es expulsada. Incluso yo estoy amenazada en estos momentos por esos grupos.

CM: ¿Estás amenazada por ser una persona trans o por ocupar una zona que quiere ser usada para otra actividad?

DN: Yo estoy amenazada porque a partir de mi transgeneridad he logrado conquistar espacios, he logrado incursionar en muchos ámbitos: a mí se me escucha, tengo ya un good will, por llamarlo de alguna forma. Soy consultora en el Distrito para los temas LGBT y prostitución, la gente acude a mí para denunciar, para hacerme saber conductas irregulares que están sucediendo y ellos piensan que porque soy transgenerista tengo menos derechos, o no tengo derecho de hacer el trabajo que hago. ¿Cómo ha logrado todo eso, cómo está haciendo todo esto si, como dicen ellos, es un marica?

Panfleto para una marcha de apoyo a los derechos de las mujeres trans

CM: ¿La Corporación tiene una definición categórica sobre el ser transgénero?

DN: Nosotras dependemos de la autodefinición, de la autodeterminación, de la autoconstrucción de la persona. Si tu vienes con barba, bigote, vestido de traje y me dices que eres una persona trans, para la Corporación eres una persona trans. Muchas personas expresamos nuestro género de manera vehemente, pero otras prefieren considerarse, construirse, actuar, pero tener una expresión de género contraria. Eso es lo que está tratando de reformular lo queer. La teoría queer rechaza lo binario del género, rechaza los estereotipos, la categorización y nosotras estamos muy de acuerdo con eso.

Charlotte Ezneda Callejas, cuyo nombre legal es Carlos Alejandro Díaz, es cubana, trabaja en la Secretaría de Salud como referente en la política LGBT y cuando me preguntan por ella me preguntan por Luis Alejandro y les digo ¿y ese quién es? La cubana, ¡ah Charlotte! Yo siempre lo llamo Charlotte porque esa es su construcción identitaria, porque ese es su deseo y cuando la veo le digo: Charlotte a pesar de que vino disfrazada de hombre hoy. Para mí siempre va a ser lo que ella quiere ser. Tengo señores que vienen a asesorarse, los llamamos trans de closet y vienen a buscar cómo pueden construirse de una mejor forma, cómo pueden expresar el género que desean. Yo, desde que entran por esta puerta, los llamo como ellos quieren llamarse.

CM: Vengo de Noruega donde, como estrategia política, las personas transgénero quieren hacer la transición completa; operarse y cambiar de género legalmente para ser cobijadas por la ley de una manera distinta. Esta es una estrategia para poder manipular los códigos de la sociedad y conseguir los derechos. ¿Qué piensas tú de eso?

DN: Es una estrategia totalmente válida, pero aquí en Colombia estamos totalmente jodidas por la ley 100. En la ley 100 todos estos procesos de reasignación sexual o transformación corporal se consideran procedimientos estéticos y no son cubiertos por la seguridad social. Por ese lado tenemos los procesos trancados y ahora, con los decretos de emergencia social, peor todavía porque habíamos logrado que algunos médicos brindaran la posibilidad de un tratamiento hormonal a las personas que desean hacer ese tránsito hasta donde quieran llegar. No todas las personas transgeneristas quieren reasignarse sexualmente, es válido apropiarse de una cantidad de cosas de esa categorización en forma positiva pero aquí en Colombia las autoridades lo usan en forma negativa.

Participamos en la campaña contra la patologización de la transexualidad y tuvimos discusiones internas dentro del grupo porque muchas compañeras pensaban que si nos consideraban enfermas nos tendrían que curar, podríamos acceder a los tratamientos porque tenemos disforia de género y les dije: es un mal entendido porque lo que te van a curar es esa incongruencia psicológica que tienes con tu sexo biológico, para que te sientas bien con tu sexo biológico, no para que consigas el género al que quieres pertenecer.

La Constitución Política de Colombia nos da un amplio abanico de posibilidades, podemos apropiarnos de una cantidad de cosas: la salud es un derecho constitucional, la vida digna, el libre desarrollo de la personalidad: Colombia, en avances legislativos, está a la vanguardia, pero en el reconocimiento, en el establecimiento de acciones que lleven a que las personas podamos ejercer de manera adecuada todos esos derechos constitucionales estamos fregados.

CM: ¿Esos derechos constitucionales no se reflejan en la calle?

DN: No se reflejan en la realidad y ahora que ganó el partido de la U y el partido Conservador, peor.

CM: Pero ¿se reflejan en las instituciones estatales es decir; en el sistema de salud?

DN: No.

CM: ¿Cuáles son los derechos que tienen las personas transgénero en Colombia?

DN: Derecho a vestirme de mujer si me quiero vestir de mujer y vestirme de hombre si me quiero vestir de hombre, es todo.

Excerpto de un texto sobre Diana escrito por Rachel Godfrey en The Panama News

CM: Y si te grito por la calle o te pego ¿tienes la posibilidad de demandarme?

DN: Hay una circunstancia de agravación punitiva en el código penal colombiano, en el artículo 58 numeral 3, que habla de agravación por discriminación por orientación sexual o por género. En Colombia tampoco hemos avanzado mucho en eso. Se piensa que el género depende de mi sexo biológico y no hemos hecho la deconstrucción de ese concepto. Los fiscales y las autoridades conocedoras en primera instancia de los procesos no dejan plasmada la motivación de esa agresión. Si yo te doy un golpe y te causo alguna lesión, puedo ir detenida si me denuncias por lesiones personales, pero no por el hecho de que seas hombre, mujer, gay, lesbiana, transgenerista o bisexual, eso queda invisible aunque haya sido el motivo latente. Ese es un reclamo que estoy haciendo al movimiento social, la apropiación de esas herramientas, el exigir que todo lo que digas en una audiencia pública, en una denuncia, quede plasmado, lo pido a mis compañeras: expliquen bien, no solamente que “el tipo me pegó”.

CM: La labor de la Corporación ¿incluye un trabajo de orientación comunitaria?

DN: Hemos avanzado mucho en este sentido. En Bogotá ya tenemos una red distrital de personas trans que estamos empoderando, fortaleciendo, a la que le estamos brindando herramientas. El año pasado tuve la oportunidad de ejecutar un proyecto en el marco de fortalecimiento de organizaciones sociales para el IDEPAC, que tenía como fin crear la red distrital de personas trans. A partir de esa red hemos logrado tener incidencia en proyectos. Ya empezamos un proyecto de visibilización y capacitación en derechos humanos para que las personas sean formadoras de formadores, para que las personas creen sus propias herramientas cualitativas y cuantitativas, para recopilar toda esa información. Vamos a hacer una cantidad de festivales, una cantidad de cosas inter locales y distritales. A nivel nacional ya dinamizamos los procesos en el eje cafetero, logramos sentar a un secretario de gobierno con nosotras y comprometerlo con la población, en Popayán lo hicimos hace 15 días y pensamos seguir haciéndolo en 8 ciudades más. Lo haremos con los recursos que recibimos de una fundación holandesa que se llama Mama Cash.

CM: Me llevas a la siguiente pregunta ¿hay una red de trabajo a nivel nacional o regional en relación con estos temas?

DN: Estamos empezando. El trabajo han sido fuerte, pero en orientación sexual. Yo lo digo coloquialmente: era mucho más fácil trabajar entre nosotras y nosotros cuando en Colombia solamente nos llamamos maricas y areperas. Pero cuando empezamos a usar el acrónimo LGBT, que lo usamos mal porque lo acortamos, nos categorizamos, creamos divisiones entre los grupos. En procesos organizativos, de participación y de todo están más fuertes las lesbianas porque han tenido acceso a muchas cosas. Los gays, a pesar de que empezaron todos estos procesos, se quedaron atrás. Los bisexuales todavía están muy escondidos. Es mucho más fácil que una lesbiana, un gay, un bisexual pasen desapercibidos o de agache, como digo yo, que una persona transgenerísta. A nosotras no nos interesa pasar desapercibidas, a nosotras nos interesa ser reconocidas en toda nuestra dimensión. Cuando te presentas a algún trabajo no te preguntan cuál es tu orientación sexual.

CM: Te preguntan cuál es tu género?

DN: No, de hecho te presentas y dan por sentado este es un hombre, se viste de hombre, tiene el cabello corto, es un macho heterosexual. Dan por sentado eso, que tu eres heterosexual.

CM: Y si llega una persona vestida como tu, ¿qué pasa?

DN: He hecho ese ejercicio muchas veces y lo he hecho en uno de los dos campos que tenemos más posibilidades nosotras. Llamamos a 25 avisos que salían en el periódico pero al final cuando tenía la cita le decía: yo soy travesti, ¿hay algún problema con eso? ¡Ay no! contestan, la gente no está acostumbrada aquí a eso; y me cuelgan el teléfono. Somos motivo de burla. Cuando me presenté a la universidad de Antioquia, la secretaria del departamento de admisiones me llamó y me dijo: por un error resultó la foto de una dama pegada ahí en su formulario, no sabemos por qué, cómo podemos corregir eso. Le dije: ninguna dama, soy yo, yo soy travesti, ¿hay algún problema con eso? No, de ninguna manera dijo. Conversamos y obtuve mi cupo en la universidad.

Marcha por derechos trans en Bogotá, 2009, foto por Bianca Bauer

http://www.flickr.com/photos/biancita/3673830458/in/photostream

CM: ¿Tienen la posibilidad de cambiar de nombre, de cambiar de género legalmente?

DN: De nombre si, de género no.

CM: O sea que oficialmente ¿eres Diana Navarro?

DN: Yo no he cambiado mi nombre porque tengo una posición política al respecto. De qué vale que en mi cédula me llame Diana Navarro San Juan si va a seguir apareciendo la variable de sexo masculino. No me están reconociendo en toda mi dimensión. Para mí no vale la pena. Muchas de mis compañeras se sienten atraídas por eso y sienten que ese es un paso adelante, pero yo no lo considero así, yo considero que la variable del sexo en las cédulas se debe eliminar. En las cédulas nuevas, en los cupos cedulares del billón, ya se eliminó. Pero en las cédulas antiguas todavía sigue apareciendo, entonces nosotras, las personas que fuimos ceduladas antes del 2000, seguimos teniendo el mismo problema.

CM: ¿El cambió en las cédulas fue por este tema?

DN: No, fue porque se consideró que ya había demasiada población y muchos números de documentos, tú tenías un número en tu cédula, en tu pasaporte, en tu pasado judicial, en tu seguridad social, eran miles de números para cualquier cosa. Entonces se llegó al acuerdo de que debíamos tener un número único de identificación personal el NUIP y no podemos seguir usando la variable de sexo, masculino o femenino.

CM: ¿Se vieron beneficiados como comunidad?

DN: Exactamente, un beneficio indirecto.

CM: ¿Me puedes hablar de la situación en el ámbito social; los baños y todos esos asuntos en los que el género binario es predeterminado?

DN: En algunos casos hemos tenido problemas, pero en las universidades, los teatros o los centros comerciales ya logramos ese respeto. Aún falta mucho.

CM: ¿Puedes utilizar el baño que quieras?

DN: Normalmente uso el femenino. Pero, en un cementerio en el que estábamos asistiendo a la cremación del cuerpo de una compañera, mis compañeras pidieron utilizar el baño y se les quiso impedir el ingreso al baño de mujeres, yo me tuve que parar y decirles: no señor, ellas entran al baño de damas porque ellas son mujeres trans. ¿Cuándo ha visto una mujer orinar parada? dije.

Es una lucha continua, es una lucha constante que no se puede descuidar en ningún momento ni por ningún motivo. Los procesos pedagógicos deben ser constantes. Ese es un descuido que hemos tenido; se piensa que porque tenemos una política pública distrital para las personas LGBT ya todo está listo, ya todo está hecho. No, todo está por hacer, el trabajo nacional está por hacer, porque no es posible que solamente en una ciudad de Colombia haya una política pública.

CM: ¿Cuál es la relación que tienen ustedes con Colombia Diversa y cuál es la tarea que hace Colombia Diversa para la comunidad trans?

DN: Las trans en el mundo entero hemos detonado todos los trabajos por la visibilización. La simple presencia de una trans en un espacio es resistencia política, pero nos hemos quedado atrás. Colombia Diversa ha logrado avances solamente para personas del mismo sexo. No veo en qué más haya trascendido. Falta articulación, respeto en el trabajo, mayor reconocimiento de las diversidades, porque todavía hay mucha discriminación dentro de nuestros grupos.

CM: ¿Están en comunicación con las directivas de Colombia Diversa?

DN: En algunos espacios participamos en forma conjunta.

CM: ¿No hay un proyecto de avance en conjunto?

DN: No, no hay articulación real; facilitamos información, ellos presentan informes, recogen la información. Por eso nosotras estamos iniciando unos trabajos organizativos. La Corporación Opción ejecutó el año pasado un proyecto con el patrocinio de Astraea para la realización de un encuentro nacional de líderes y lideresas trans al que asistieron 23 hombres y mujeres trans de todo el país porque los hombres trans están muy invisibilizados aún.

CM: A lo largo de esta entrevista has estado hablando de nosotras y nunca de nosotros, ¿cual es la situación de la comunidad trans de hombres?

DN: A partir de un diagnóstico nacional y distrital que hice pude concluir que los hombres trans están en una situación tan o más difícil que las mujeres trans. Nosotras nos podemos visibilizar y tenemos una resistencia de hecho; el género femenino es muy fuerte, muy rebelde, muy trabajador. Los hombres trans están en una desventaja total, muchos de ellos han logrado una transformación corporal que les facilita mimetizarse con el resto de la población, pero aún tienen los problemas que tenemos nosotras: en los cupos cedulares, en el acceso a servicios que la salud. Empezamos a integrar en nuestros trabajos a los hombres trans porque es necesario que se escuche también la voz de ellos.

CM: ¿Hay líderes entre los hombres trans?

DN: Hay grupos, hay uno de niños y adolescentes trans; en Pasto conocemos algunos, en Cali también y aquí en Bogotá hay otros, pero el movimiento no ha tenido todavía esa fuerza necesaria como para visibilizarse. Estamos buscando que ellos mismos traten de organizarse, hagan parte de la organización de personas trans, pero también que conformen sus propios grupos, que luchen por sus propios intereses tal como a nosotras nos tocó hacer al principio.

CM: ¿Cuál es la relación que tienes tú personalmente, tu comunidad o la Corporación con teorías feministas y con relación al feminismo?

DN: Aquí en Colombia las mujeres han luchado mucho por conseguir espacios de reconocimiento, pero paradójicamente aún discriminan a los hombres biológicos que nos construimos en el género femenino. Algunas feministas continúan leyéndonos desde una perspectiva binaria, patriarcal, machista, heteronormativa, a partir de nuestra genitalidad y nos leen como masculinos.

CM: O sea que no hay una relación digamos teórica o de implementación de políticas?

DN: Exactamente y como aquí las políticas públicas se han encargado de atomizar la población, yo veo un aspecto muy negativo en la separación de las poblaciones, no hay una articulación social real y eso hace que cada persona se preocupe de su pedacito y no ejerza la solidaridad que le correspondería para que toda la sociedad colombiana tenga el mismo acceso al ejercicio de sus derechos.

CM: Una pregunta en relación con la representación de las personas transgénero en los medios y en el ámbito cultural; ¿cual es esa situación hoy en día, en relación con el pasado?

DN: Se avanzó un poco, no mucho. Ha habido varios momentos, aquí se nos presentó en televisión como la loca, caricaturesca, ridícula, como el payaso. í‰ramos solamente peluqueras, floristas, modistas, maquilladoras, con unas actitudes muy caricaturescas y exageradas. Eso hace parte también de nuestro grupo, pero no es todo el grupo. Después cambió y ya no se presenta a esas figuras, sino al criminal, al delincuente. Con la presentación de una novela, Los Reyes, la compañera Endy Cardeño empezó a construir muchos imaginarios, no solamente la prostituta, la peluquera, la modista, sino una persona que en su interioridad puede ejercer cualquier profesión. En Estados Unido Ru Paul tiene su propio programa de televisión, pero desafortunadamente no llega a Colombia. Esos espacios han permitido que en los medios no se nos caricaturice, no se nos estereotipe y hemos podido avanzar un poco en la deconstrucción de esos imaginarios.

Aún falta todo el camino por recorrer, porque por ejemplo a pesar de que tenemos una persona trans como coordinadora de investigación del Instituto Humboldt, hay muchas de las personas que han logrado surgir o tener éxito que se han olvidado de las que no tienen el mismo privilegio.

CM: Me llevas a hacerte una pregunta que es de gran interés para mí y es que Colombia es en esencia una sociedad dividida por la clase y por la situación económica y yo supongo que este debe ser un tema que debe ser fuerte dentro de tu comunidad. ¿Hay unidad con las personas que tienen acceso a medios económicos y educación?

DN: No, desafortunadamente no hay unidad. A nosotras se nos vende el sofisma desde pequeñas de que tenemos que ejercer la prostitución para conseguir un capital importante, conseguir un patrocinador, irnos a Europa donde podemos conseguir mucho dinero a través del ejercicio de la prostitución. Empezamos a operarnos, a comprar casas, bienes materiales y con eso creemos que nuestra inserción en la sociedad está garantizada. Yo consigo colaboración de personas heterosexuales con más facilidad que de compañeras que económicamente están estables en estos momentos.

CM: ¿Qué pasa con las personas trans de clase alta? ¿Hay alguna comunicación?

DN: No. Hay un clasismo exagerado y es grave porque todo el trabajo lo estamos haciendo hacia afuera y muy poco hacia adentro. Yo me atrevería a decir que las dos únicas organizaciones que hacen trabajo en esa doble vía hacia el interior y hacia el interior en el campo trans, somos la corporación Opción y Trans Colombia. Queremos que el otro nos respete, que respete nuestros derechos, que el Estado garantice el ejercicio de nuestros derechos, pero las compañeras no saben cuáles son esos derechos. El derecho al libre desarrollo de la personalidad, el derecho a tener una vida digna, el derecho al trabajo, a una vivienda digna, pero no solamente son los derechos fundamentales, sino son derechos económicos, sociales y culturales, todos esos derechos. A esos derechos también tenemos que tener acceso, no solamente al derecho pasar por cualquier parte y que no se nos maltrate, ridiculice o ser de agredidas por el hecho de ser lo que somos, tenemos todos los derechos que tiene un ser humano, todos y en eso no hemos avanzado todavía.

CM: ¿Cuál es el siguiente paso? Me da la impresión de que estamos en una situación un poco primaria todavía.

DN: Si, estamos empezando. Tenemos una herramienta importante que es la política pública distrital para la garantía de los derechos de las personas LGBT, pero falta mucho trabajo para implementarla, para llevarla a cualquier rincón de la capital. A partir del trabajo que estamos haciendo, con la Dirección de Diversidad, se nos reconocen algunos derechos: el derecho al trabajo, a la seguridad, a la vida, a la cultura y a la educación. Aumentó la participación, pero aún no se reconocen todas nuestras especificidades y es muy difícil que se vayan a reconocer. Hemos empezado a enseñar a la gente las bases para que logren soltarse, defenderse solas, organizarse, no solamente defender sus derechos, sino los de todo un grupo. No descuidamos la incidencia política por el conocimiento que tenemos, por las herramientas que hemos adquirido, por el nombre que hemos desarrollado aquí en Bogotá, no descuidamos otros espacios de formulación de políticas, porque aquí una ley, un decreto, una norma dinamizan muchas cosas.

CM: ¿Cómo se financia la corporación?

DN: La Corporación Opción ha tenido financiamiento en dos ocasiones consecutivas de la Corporación Lesbiana para la Justicia de Astraea, Estado Unidos. Gracias a esos aportes pudimos desarrollar unos proyectos con el Instituto Distrital para la Participación de la Acción Comunitaria el IDEPAC, cuyo producto fue la red distrital de personas trans. Mama Cash nos otorgó 23.000 euros este año por eso pudimos comprar equipos y este año nos vamos a poder dedicar 188% a este trabajo; ya no nos tenemos que preocupar por más nada.

CM: ¿El gobierno nacional está completamente desinteresado del trabajo que están haciendo?

DN: Al gobierno nacional le interesa cooptar el trabajo de las organizaciones sociales. Te explico un poco: nosotras hacemos el trabajo, hacemos unas mesas de concertación y firmamos un decreto que muchas veces es mal firmado, generamos una política mal firmada y ese es trabajo del gobierno. A nivel de financiación, no existe una política, incluso el Presidente ílvaro Uribe nos considera delincuentes porque muchas denunciamos, no nos quedamos calladas.

CM: ¿A las transgénero o a las personas que ejercen el trabajo?

DN: A las personas que ejercemos la prostitución, a las transgeneristas, a las LGBT. Nosotras participamos en todos los informes sombras, en todas las visitas de la Alta Comisionada de las Naciones Unidas y denunciamos, llevamos pruebas de los procesos que no han sido terminados. Porque el año pasado la ONU le pidió un informe de derechos humanos a la Presidencia y ellos dijeron: aquí todo está bonito, todo está bello, aquí se pueden casar, aquí iniciamos la discusión de un proyecto de ley para parejas del mismo sexo, aquí la Corte Constitucional dijo esto. No señor: no todo está bien, no todo está bonito. Miren tantos homicidios, tantos procesos no fallados, tantas personas desaparecidas, todo este conflicto, ¿cuál proyecto de ley? si se ha discutido en cuatro ocasiones y se ha hundido, ¿cuál avance legislativo? aquí no nos podemos casar, sólo podemos hacer un reconocimiento de nuestra unión marital de hecho a partir de un pronunciamiento que tuvo la Corte Constitucional. Ni siquiera el Gobierno, la Corte Constitucional tuvo un pronunciamiento equiparando esos derechos, basándose el derecho al libre desarrollo de la personalidad y el derecho a la igualdad. Entonces dijimos: no, eso es mentira.

CM: ¿Hay algunos de los candidatos presidenciales que tratan este tema, o nadie lo aborda?

DN: Realmente no. Pese a que el Polo Democrático alternativo, el partido político del que yo hago parte, tiene una cuota de discriminación positiva para la participación política de personas lesbianas, gay, bisexuales y transgeneristas, Gustavo Petro, candidato oficial del partido, no se ha pronunciado, tuvo una reunión desafortunada con algunas compañeras, en la que dijo que no se comprometía con nada, que solamente quería escuchar.

CM: En un país que vive un ambiente de violencia política y de desigualdad social tan brutales como Colombia, ¿los problemas de identidad de género no serán vistos como un punto sin importancia en la agenda?

DN: Desafortunadamente si, porque no es solamente el hecho de tu te acuestes con otro hombre, otra mujer o un hombre y una mujer, o que te quieras vestir de hombre o de mujer. Minimizando la problemática se ha visto así. No tenemos acceso a la salud, no tenemos servicios con un enfoque diferencial que se adecuen a nuestras especificidades y a nuestras necesidades, no los tenemos. Yo le decía a un Senador: a mi que carajo me hablan de un derecho al libre desarrollo de la personalidad si yo no tengo servicios médicos, no puedo transformar mi cuerpo para cohonestar con el ideal femenino o con el ideal masculino que yo quiero, que no es un simple capricho, que no es un simple invento, es una necesidad mía y una necesidad que pasa por un acompañamiento psicológico, médico, interdisciplinario. No tengo esos servicios diferenciales, no los tengo. Cómo voy a desarrollar libremente mi personalidad si yo no tengo derecho a la salud, si no tengo derecho al trabajo porque me visto de mujer siendo un hombre. Cómo voy a tener derecho al libre desarrollo de la personalidad si no tengo una vivienda digna. Vivo como una reina porque vivo en un apartamento que tiene unas condiciones higiénico sanitarias adecuadas, que cumple con ciertos estándares. Pero si vamos y hacemos un recorrido en los sitios en donde viven muchas compañeras, viven en unas habitaciones de dos por dos, en donde escasamente cabe una cama, unos baños asquerosos, en pésimo servicio. Muchas de mis compañeras van a una agencia de arrendamiento para que les arrienden un apartamento y se los niegan. Yo, por la hoja crediticia que tengo hace años, y porque no querido cambiar mi nombre, mando el formulario con mi nombre legal.

CM: ¿Cuál es tu nombre legal?

DN: William Enrique Navarro San Juan. Con mi nombre legal, con todos los soportes financieros que tengo de mi tarjeta de crédito, de mi cuenta de ahorros, de todos los créditos que he tenido, que tengo, de todo mi historial crediticio, yo lo paso sin presentarme, lo mando con mi secretario, por correo, por cualquier medio y la solicitud es aprobada. Después de aprobada, cuando me presento, me tienen que entregar las llaves, después de firmado un contrato ya no pueden hacerle a uno nada, pero muchas de mis compañeras no tienen ese acceso, entonces también dependen de terceros que hasta las explotan para que puedan tener unas condiciones medio dignas.

CM: Diana, estamos ya terminando, háblame de temas de salud sexual. ¿Tienes información de los índices de VIH u otras enfermedades?

DN: Simplemente no, la educación sexual y la salud sexual reproductiva no se basan simplemente en infecciones de transmisión sexual o VIH-Sida, pero se nos ha categorizado de tal forma que son enfermedades exclusivas de nosotras. Llego con un dolor de uñas al médico y me dice: ¿ya te hiciste la prueba de Sida?

CM: No solamente la comunidad de transgénero, los homosexuales también...

DN: ¡Claro! ¿Ya te hiciste la prueba de sida? ¿Usas condón? Como si toda la salud sexual y reproductiva fuera eso.

Aquí anualmente se presentan reportes distritales por localidad sobre la prevalencia de la infección VIH y las personas en ejercicio de la prostitución somos las que menos tenemos. No solamente porque somos conscientes, sino porque que sabemos que si nos contagiamos de cualquier enfermedad no podemos seguir siendo productivas. El año antepasado, cuando estuve haciendo todos los viajes para la construcción del encuentro y la formulación de la propuesta de trabajo con personas trans, les decía a mis compañeras, enséñame a poner un condón, y no sabían. De igual forma, el uso de lubricantes no está incluido en estas capacitaciones, se nos dice que no se puede usar vaselina, que no se puede usar lubricantes a base de aceite, pero no se nos dice qué podemos usar y tampoco tenemos acceso a los lubricantes. El gobierno nacional piensa que repartiendo condones va a cumplir con ese objetivo del milenio. Las cátedras de educación sexual no funcionan en el colegio. Están permeadas por esos moralismos judeocristianos de los que te hablo. Lo que te enseñan en el colegio es que tienes un pene, unos testículos, para lo que sirven, nada más. No enseñan que hay posibilidad de tener relaciones sexuales a temprana edad, que nuestro despertar sexual empieza a los diez años, que cuando llegamos a los catorce ya tenemos la posibilidad de interacción. No se nos enseña la sexualidad responsable; se la sataniza. No hay cátedras de educación sexual reales, conscientes, que nos enseñen toda esa gama de posibilidades, que nos enseñen el respeto por nuestros cuerpos, el respeto por el cuerpo de los demás, cómo disfrutar de nuestro cuerpo sin lastimarnos a nosotros mismos, sin lastimar a otras personas. No hay una cátedra de educación sexual, únicamente te dicen use condón, póngase el condón para que no le transmitan nada y no se muera.

CM: Muchas gracias y mucha suerte con esto, Me parece que estás haciendo una labor titánica.

DN: ¡Hay Dios mío!

Enlace: Corporación Opción por el Derecho de Hacer y el Deber de Hacer

↑Arriba