Presentation

by Carlos Motta and Cristina Motta

People are not provoked by those who are different.What is more provoking is our insecurity: When you say, “I am so sorry but I am different.” That’s much more provoking than saying “I am different,” or “I have something to tell you, I can see something that you cannot see!”

With these words, Norwegian Trans activist Esben Esther Pirelli Benestad situates sexual difference as a unique opportunity rather than as a social condemnation.“Difference” is a way of being in theworld, and as such it represents a prospect of individual and collectiveempowerment, social and political enrichment, and freedom. Freedom implies the sovereignty to govern oneself: Being human is being beyond parameters, being without sex or gender constraints.

Hasthis ideal been attained in the four decades of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans,Intersex, Queer and Questioning politics?

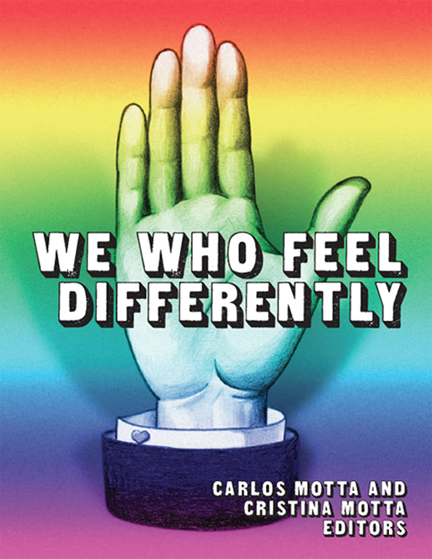

We Who Feel Differently approaches this and other questions through fifty interviews with LGBTIQQ academicians, activists, artists, politicians,researchers and radicals from Colombia, Norway, South Korea, and the United States. The interviewees have been active participants in the cultural, legal, political, and social processes around sexual difference in their countries, and they frame the debates, expose the discourses and some of them criticallydiscuss the LGBT Movement’s agenda from queer perspectives.

Thissection presents five thematic threads drawn from the interviews, identified to construct a narrative that is representative, yet not comprehensive. This bookis not a survey or a statistical study; it puts forth an assemblage of queercritiques of normative ways of thinking about sexual difference.

TheEquality Framework: Stop Begging for Tolerance, gathers opinions about the conceptual perspective that guides the claim for rights and validates their recognition by the State. This framework, founded on formal equality, causes significant doubts and frustrations, all of which start a productive discussion on the limits of legal formalism and liberal tolerance and the need for a more substantive moral debate and cultural transformation.

Defying Assimilation: Beyond the LGBT Agenda assembles perspectives on‘difference.’ It vindicates a critical and affective difference that expresses skepticism about legal responses, a firm reluctance to be assimilated, and astrong resistance to be conditioned and disciplined. The interviewees articulate ways to deal with these circumstances and the actions they have undertaken to empower themselves and others.

Gender Talents brings together the voices of trans and intersex activists and thinkers who reject the binary system that organizes gender and sexuality. Their ideas aim at broadening the possibilities of an individual beyond normative categorizations of identity. They also struggle to avoid classifications and to abolish all forms of control overnon-normative lives and bodies.

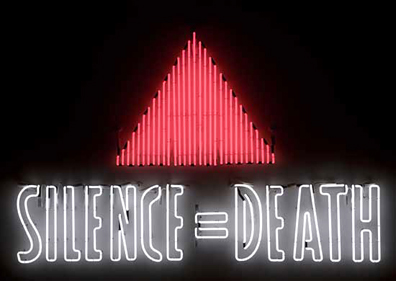

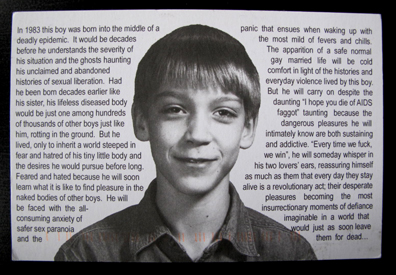

Silence, Stigma, Militancy andSystemic Transformation: From ACT UP to AIDS Today offers a brief description of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in the United States andof some of the strategies used by this social movement to confront thegovernment’s response to the AIDS epidemic from the perspective of some of its members. They also reflect on the status of AIDS today.

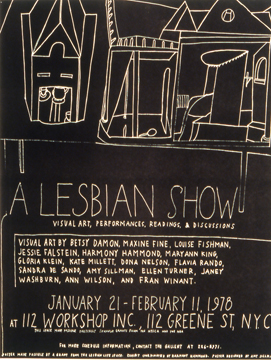

Queering Art Discourses provides an analysis of the reign of silence aroundthe discourse of sexuality in art and discusses the works of cultural producersthat attempt to break that silence.

We Who Feel Differently attempts to reclaim a queer “We” that valuesdifference over sameness, a “We” that resists assimilation, and a “We” that embraces difference as a critical opportunity to construct a socially just world.

↑Top

The Equality Framework: Stop Begging for Tolerance

Thelast four decades have been productive in regard to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual andTransgender (LGBT) rights activism and legal politics. Numerous countries inthe Global North have improved the status of their LGBT citizens: Homosexualityhas been de-criminalized, anti-discrimination bills have been implemented, anda heated debate on same-sex marriage has made gays and lesbians more visible.These changes, from a condition of absolute oppression to having a greaterdegree of social and political visibility, are partly the result of decades ofgrass roots community organizing and activism, institutional lobbying andpolitical advocacy.

ManyLGBT people have endorsed these achievements but, at the same time, they havebeen largely censured. Critics coming from within the legal field have judgedthat liberal reforms are unable to provide substantive equality. Queer critics,external to the legal sphere, have viewed these reforms as an extension ofprivileges to those who benefit from traditional hierarchies, such as those ofclass, ethnicity, gender, or race; or as conforming to heteronormativity.

Theideal of equal treatment under the law is at the heart of these changes.Equality establishes that all people should be treated equally under the law,and if they are “different,” they should have the equal right to be consideredin terms of their differences. This principle works under the constraintsderived from formal equality and state neutrality regarding moral debates andtheories of the good life.

Howwell these reforms have performed, the scope of their achievements and theirinitial deployment vary from country to country. In Latin America, legalactivism has been actively shaping, not without obstacles, a new politicallandscape in several countries. In Colombia, as pointed out by Marcela Sánchez,director of Colombia Diversa, an LGBTrights organization, “(…) the most important precedent is the 1991Constitution. The articles related to equality and the free development ofpersonality do not mention the issue of sexual orientation, but a wideinterpretation of these articles served to encompass issues of non-normativesexuality.” Colombian activist and lawyer Mauricio Albarracín adds, “(…)Duringthe 1990s, a very progressive jurisprudence concerning the protection of gaysand lesbians was established. As of 1999, different bills proposing therecognition of the rights of same sex couples —basically, property and socialsecurity rights — were developed. In that context, in 2003 there was a billsupported by a group of activists, but when this initiative was defeatedseveral activists decided that there should be an organization devoted to foster same-sexcouples de facto recognition.”

Othercountries, those that have already conquered formal equality, are currentlyconcerned with the construction of a broader cultural framework that willprevail over formal equality and will search for a deeper transformation ofsocial prejudices. This is the case of Norway, where the legal struggle overformal equality has been successful, but substantive equality, that is, thesearch for equal outcomes between the law and social life is, nevertheless,still pending. Karen Pinholt, Executive Director of LLH, The Norwegian LGBT Association, assertsthat “ (…) up to the middle of last year, when it was agreed that we shouldhave full marriage rights, it was a legal question: To have equal rights underthe law. Today we have put much of that legal fight behind us because thoserights are there. The fight now is elsewhere. We aim at having not just legalequality, but also real equality inour everyday lives. Our main tool in that fight is to increase awareness andthe competence in LGBT issues in the general population, but also with peoplewho work with others professionally: Health workers, people working in schoolsand education, leaders in management, etc. Most often in Norwegian society,they would like to treat us equally, but there is a lack of competence on howto do it. This means they often just ignore us, and ignore the fact that wesometimes need some special considerations to be properly treated as equal.”

Thosewho have endorsed the legitimacy and inevitability of the legal framework, asKaren Pinholt has, believe “(…) that having the laws makes us equal. The legalframework is a strong and important signal for Norwegian society. Without thatas a backing, all the negative things that we experience out in the real worldderive from the fact that we are not equal before the law. Now that we areequal before the law, it is very difficult for our opponents to say: ‘I havethe right to treat you badly.’ Now they have to find other ways to make theirarguments. Since we are equal before the law, they see that the society atlarge and the lawmakers recognize us as human beings with equal rights. Thatmeans that it is much more difficult to treat us badly, but that doesn't meanwe are not treated badly. There are sub-communities in Norway where it is definitelynot okay to be gay.”

MauricioAlbarracín has also underscored the symbolic effect of legislation: “InColombia, a former Ejército de LiberaciónNacional (ELN) guerrilla commented that recently he could finally be openlygay in his group. This is not representative, but I thought it was an indicatorthat something is happening, and what is happening is that issues addressed inpublic discussions are beginning to infiltrate non-traditional places, orplaces that were traditionally homophobic. I think public discussion is veryimportant; I don’t know how much it will contribute to people being moretolerant or less violent, but it does generate transformations and, at least,it brings a political project to light. In Colombia and in Latin America thereis a political project that contemplates the recognition of gays, lesbians,bisexuals and transgender persons. Legal decisions transform reality insofar asthey destabilize an order. It is not as though they magically change reality,but they introduce an authoritativepoint of view, and that point of view develops socially. I think this has beena beneficial influence in the case of couples. Court decisions entail severalbenefits; a strictly speaking political one is that those legal proceedingscreate a network, an ensemble of stakeholders who meet through theirinvolvement in the lawsuit and continue to participate in order to guaranteethe rights obtained. Their effect also implies the existence of a group ofpeople who have worked on the issue and this generates growing adhesion. Thatgroup will work to preserve the change in the long term. Additionally, this maygive rise to a cycle of protest, that is, a cycle of mobilization; because somerights have been obtained, people begin to realize that there are other rightsthat have not, or that there are other types of discrimination and violence,and they begin to work in those areas. This action triggers other movements andother mobilizations in other spheres. Another benefit is that by recognizing theyhave rights, same sex couples gain empowerment when faced with the authorities.People over 35, 40 or 45 years of age, who have been in a relationship for 15years, decide to proclaim their union after having lived inside the closet. Atpresent, law students read judgments that protect same sex couples and theyquestion themselves about the ruling on marriage, different questions to thoseposed five or ten years earlier, because the context is different. The debatehas shifted to a different place, there is a political discussion going on;politicians promise things, there are politicians who are openly gay orlesbian, and there are public policies. There have been many changes.”

NorwegianLGBT rights advocate Kjell Erik Øie explains that “(…) There are two goodthings about legislation: One is that the government has said, ‘It is okay. Wesupport it. We think it is great that you find each other.’ The other thing isthat especially after we achieved the Partnership Law, we became very visible.Now that actually has changed because we have one law for everybody, theMarriage Act, but before, when we had to fill out official forms, we had tostate whether or not we were married or lived in a partnership. Everybody knewthe word partnership implied the difference between straight and gay people.After the Partnership Law came into effect, suddenly people talked aboutpartnerships, legalized their partnerships, and straight people celebratedtheir gay and lesbian friends that wanted to live together. But now that wehave the Marriage Act, and the Partnership Law is dead, we are invisibleagain.”

InKorea, where legal reforms on the basis of sexual difference are far from beingpart of the government’s agenda, the LGBT community is demanding its legalrights. PARK Kiho, Director of Chingusai,a Korean gay rights organization in Seoul, thinks: “(…) I get that questionvery often: ‘What changes have been made in people's lives since you havestarted this organization?’ But it is always very difficult to answer becausethose changes aren't quite apparent. Korea is a Confucianism-dominated andmale-dominated society. Unlike in Western nations, no new laws or systems havebeen created that might prove the actual improvement in the lives of sexualminorities. Nothing legal has changed in the past 20 years. The changes thatare visible to us are rather of an unofficial character: Chingusai's office is much larger than before, more people visitus, and more people are speaking out (...) Now there are six or seven moregroups like Chingusai, and the numberof clubs, blogs and websites where sexual minorities can express themselves hasexplosively increased.”

PARKKiho also admits: “I will have to agree that we need to learn from Westerndiscourses; they have more variations and therefore they can more efficientlyanalyze or explain the present lives of sexual minorities. But all thehistorical stages that Western societies went through step by step, didn’t takeplace in Korea. Everything was imported at once somewhat recklessly, afterwhich the Korean queer community faced a complex situation: Our actual livesare still oppressed, but the media is flourishing with images of an opensociety. To really change people's lives, it is crucial to adapt Westerndiscourses to the Korean terrain; and there is little difference betweenadapting and re-creating.”

Theequality framework that has encouraged most of the legal victories for LGBTrights in various countries has produced distinctive dilemmas. One of themrefers to the alleged moral neutrality that informs formal equality. Criticsemphasize the need for a substantive debate on LGBT rights. The demand forneutrality, that is, the demand that the State remain impartial before thedebate on what is the good life, without attempting to impose criteria concerningthe social morality on an individual’s conduct, is a key principle ofliberalism. This principle leads to reforms based on the idea of tolerance, butdecisions and policies made in the name of tolerance have proven to beineffective in terms of guaranteeing respect for the activities they intend toprotect.

Toleranceis part of Åse Rothing’s research project at theUniversity of Oslo: “(…) School textbooks that teach about homosexuality usually start by saying that some peopleare homosexuals. At this point, they specifically go from we to they, which is adistinct move in the author’s voice. The tolerance perspective is very much thefocus. Homosexuality is said to be something that we should accept, assuming that the classroom is a collectiveheterosexual entity. Teachers and students tend to state the same kind ofthings: We have to accept homosexuals because they are just like us andthey are normal people. (…) Theyteach tolerance, but at the same time this method for teaching sexuality is away of reproducing heterosexuality as the norm, and it is also a way ofreproducing the hetero-assumed students as a group that is allowed to draw theline of what is acceptable and to outline what sort of rights they have.Homosexuality is always presented as something that is okay, if it is real, but you shouldn't try it. It is like saying: ‘If you thinkyou might be attracted to one of your same sex friends, wait and see; it mightpass off. If you are really sure you are homosexual, then it is fine. Youshould come out and tell your parents and your friends.’ That is the implicitmessage. At the same time, the teachers and the books emphasize how difficultlife is for many gays and lesbians in Norway and the difficulties they willpresumably face. I think there is a good intention behind these statements.They intend to acknowledge the difficulties and homo-negativism that exist inNorwegian society. It is like saying: ‘You will feel lonely and your parentsmight not like it. It will be difficult for you out there.’ And at the sametime, they are saying: ‘Homosexuality is fully okay in Norwegian society today,it is not a problem; but in Iran, on the contrary, they have death penalties.(…) I have also heard students saying: ‘If I discovered I was gay, I would commitsuicide.’ (…) Homosexuality is presented as something problematic, and youshould really avoid it and pray to God you will never be there. It is notattractive at all. It is not presented as something that you might like orsomething you should try out and that might bring you a good life. None of thegood stories of queer lives are made visible.”

Thearguments that guide this educational perspective are grounded on a soft ideaof tolerance, completely independent of whether these sexual practices are goodor bad. “ (…) Although homosexuality is now equal according to the Norwegianlegislation, and anti-gay discrimination bills have also protected it, it isstill seen culturally as something inferior to heterosexuality,” ToneHellesund, queer researcher at the SteinRokkan Institute for Social Studies of TheUniversity of Bergen comments. “‘The good life’ in Norway, what all parentswant for their children, the best life you can get, is still very much aheterosexual life. Even though as a homosexual, you can still have a ‘goodlife’ by having children, getting married and living in harmony as a nuclearfamily, I think most Norwegians see heterosexuality as the ideal life.”

Thedeficiencies in a substantive debate on the morality of same sex sexuality andthe excessive preeminence of the formal equality paradigm create remarkableincoherencies. Åse Rothing provides an example: “(…)When Norwegianness and Norwegianculture is defined in relationship to others, gay rights and tolerance ofhomosexuality seem to represent it. In a way, Norwegianness is heterosexuals being tolerant towardshomosexuals. But some pictures in the textbooks will create these kinds ofcontrasts. Take a look at this picture: This is about ways of living before andnow. It is about marriage and families. In one picture, you have two men and alittle girl in the middle reading a paper in the park, and in another one,there is a Masai man and a handful of Masai women in the background. It is areally primitive and dark picture. The first picture’s caption says thathomosexual partnerships are allowed in Norway. The second picture’s captionsays that Masai men can have several wives. Consequently, they make thisopposition between the really pre-modern Masai and the modern Norwegians. TheMasai are supposed to be seen as the definite opposite of gender equality,which is the ideal in Norway. One ofthe interesting things here is that in this picture a gay couple isrepresenting gender equality, but this book was published before gay couplesactually had the right to adopt children. Therefore, this picture isrepresenting Norway as a country that was gay-friendlier than it actually was atthe time. It is very paradoxical. But what happens in the chapters aboutsexuality is different. There are two different sections: One on cultural normsthat usually deals with gender and sexuality and another more traditionalchapter on sexuality. And in that chapter the we is definitely heterosexual.”

ForColombian activist and academician Franklin Gil Hernández, these deficiencieshave also distorted the LGBT Movement’s agenda: “(…) A Movement based on sexualissues should be talking about other things. I feel that the movement speaksvery little about sexuality, very little about proposing changes to thissociety, about how to experience sex, how to experience solidarity beyondmarriage, beyond a couple; it speaks very little about (…) other proposals. Iunderstand that having rights is very important, but the agenda should be moreambitious in the sense of proposing a more structured change in the sexualorder, an order that continues to discriminate; even with gay marriage, thereare many items that are left outside the agenda.”

Colombiananthropologist Fernando Serrano confirms Gil’s idea: “(…) What is happening to themovement at present is that its effervescence for the affirmation of identity(…) has made it forget other transversal spaces: Class issues, labor problems,health policies. (…) We have to think about how to construct anotherarticulation that does not eliminate differences and that does not solve thingsmerely by naming them. But what do we do to avoid the answer being: Here is thesection of homosexual bodies; here is the section of black bodies; here is thesection of indigenous bodies?”

“(…) But theimportant thing is to question what a “(sexual) minority” is, and what is tocome in the future.” Says Korean minorities activist MONG Choi. “For instance,should LGBT people adjust themselves, though somewhat segmented, to theexisting system, such as the marriage system, or should they fight forcompletely new rights? The existing system and capitalism engage with oneanother. I think the main task for us now is to change this capitalistsociety.”

Furthermore,American activist and novelist Sarah Schulman warns us against equating arhetoric of equality rights with progress: “We are constantly being told that things are so much better and wehave made so much progress. I really think we have an enormous amount ofchange, but change is not the same thing as progress. The way gay people arecontained, made secondary, and diminished is far more sophisticated now than itwas twenty years ago. (…) Gay people are being told that the only things theyneed are marriage and military service and that everything else is fine. We arebeing told we are completely treated fairly in every way and that we are anintegrated part of this country. Thirty years ago, to be anti-gay was anormative thing. Most people did not know anything about gay people; they didnot know they knew gay people, or what gay people’s hopes were. Today everybodyin this country knows an openly gay person, sees them on television, in theirfamilies, and understands what gay people stand for and/or want, so to beanti-gay today is much more dramatically vicious and cruel than it was in thepast when you did not know the names and faces of the people you wereaffecting. (…) In that context, in the U.S. we have lost every ballot measure,thirty-one out of thirty-one, in the last few years, meaning a huge number ofpeople in this country are viciously anti-gay and willing to vote anti-gay. Wealso have a president who does not support gay people, so we are in a situationwhere the opposition has a more negative meaning than it did twenty years ago,yet we are supposed to pretend this means nothing and has no impact on us, thereal people, our relatives and neighbors. Why are we being told this conditionof profound oppression is actually progress? It is not.”

↑Top

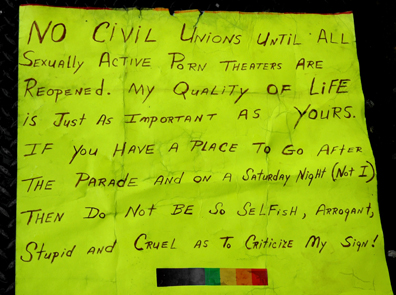

Sign at NYC Gay Pride, 2009. Photo Carlos Motta

Sign at NYC Gay Pride, 2009. Photo Carlos Motta

From Identity Politics to Queer Politics: The Risksof Assimilation

Forqueer theorists and activists, the “identity politics” that inform legalreforms tend to essentializehomosexuality, to reify identity categories, and to assimilate the subjects ithas created. Tone Hellesund considers that “(…) homosexuality is still seen as the truth about a human being. InNorwegian, we use the word legning;we speak of homofil legning, ahomosexual inclination, which I see as a very essentialist framing ofsexuality. That is a term that is very much used in the public debate and inevery day conversations amongst general people. It is assumed that if you are ahomosexual, you have this ‘inborn inclination’; your core is that you were borna homosexual, and there is nothing you can do about it. This is a very strongstory in the Norwegian context. In order to gain citizenship rights, to givehomosexuals more space and to give us the right to live as ordinary citizens,there has been a discourse focusing on homosexuality as an essence, thus promoting an essentialist agenda. There has also beena strong focus on the suffering of homosexuals. The suicide narrative is verystrong in Norway, particularly since a report was published in 1999 that showeda higher occurrence of suicide attempts among young homosexuals than amongheterosexuals. Those statistics have been used heavily by the homosexualorganization to claim rights. On the one hand, the focus on inborn identities,the essentialist understanding of homosexuality as a fundamental difference,the focus on suffering and the cry for tolerance, have been the roots that haveled to obtaining citizenship rights. On the other hand, I think it is a veryproblematic discourse. Even today, when we have citizenship rights, thatnarrative is holding homosexuals down as something fundamentally different, assomething that should be tolerated and felt sorry for.”

Accordingto Ellen Mortensen, Director of the Center for Women's and GenderResearch at the Universityof Bergen, the use of this strategyhas paved the way for the success of the legal reforms, but “(…) thetheoretical foundation for the political work done is not queer theory butidentity politics. Something that is peculiar to the Scandinavian countries isthat there is quite a short distance between certain academicians, especiallyin the social sciences, and the policy makers. For instance, within academicfeminism, they were instrumental forwarding many of these equal rights lawproposals when it comes to gender. Likewise, within the gay and lesbiancommunity that is still fueled by what I would call identity politics and theclear-cut categories of gay and straight. They have been able to makesuccessful political impact precisely because of this strategy. They have madethese legislation proposals on the basis that, for instance, gays and lesbiansare a minority group that should have equal rights. It has not been made on thebasis of queer theory, because that muddles the terrain.”

MONGChoi highlights the community-centered behavior thattakes place in Korea. “(…) Korea’s sexual minority movement is quite similar tothat of the United States. It has placed LGBT identities, coming out of thecloset, forming communities, helping each other and taking political actionwhen needed as its core mandates. However, this whole identity-centeredmovement deserves to be criticized. People satisfy and confine themselveswithin their own communities with their happy and friendly personal lifestylesand are not able to question their rights at political and social levels. Theythink: ‘Is there really a problem? Can’t we just talk it over?’ (…) We thoughtthat we needed to go one step forward from this identity-based movement, andthat is why we founded the SexualMinorities Committee of the DemocraticLabor Party (DLP). But the sexual minority issues proposed by the committeehad their limits too. They couldn’t be made into a general agenda because theyare restricted within the boundaries of the community’s specialized needs. Sonowadays we take action in a more general sphere, covering many kinds ofminorities such as immigrant workers and immigrant women. We discussminorities’ housing rights and labor rights and those things that we need toprotect from capitalism.”

Culturalprejudices may arise from clear-cut identity categories according to NormanAnderssen, Social Psychology Professor at the University of Bergen. “(…) If you talk about gender or sexualcategories, the clearer you make these distinctions and the more you thematizethem, the easier it is for people to have certain opinions about some of thesecategories. It is a kind of logic, whereby the more you insist that there arehomosexuals, bisexuals and heterosexuals, the more you let people have opinionsabout these groups. To really dissolve negative attitudes, we need to dissolveour concepts and notions of sexual distinctions, including gender. This is avery radical position in line with general queer theory: As long as we havethese very strong categories, we will also have negative attitudes.”

Whenasked whether she thought capitalism as a system has provided the space and theconditions to form and enact LGBT identities, CHOI Hyun-sook, a Korean sexualminorities activist and former out-lesbian presidential candidate, affirmed:“(…) I actually doubt whether it is capitalism that made possible the identityformation of sexual minorities. It is true that many cultural and academic discourses,especially feminist discourses, developed within the capitalist system; andthat thanks to these discourses, we were able to question the so-callednormality, which only approved of heterosexuality. These discourses threw alight on the various and unique people who were living in obscurity. But theywere always there and what they didn’t have was a name. (…) LGBT identities arenot something imported from the West; they existed at all times, in Korea, inIndia, in Thailand (...) Western theories just made it possible for them toidentify themselves as LGBT. I think that Korean LGBT people have differentidentities, different cultures and different lives from those in the UnitedStates or Europe. I can’t agree that capitalism itself played a major role onsexual minority identity formation; it can opportunistically stand on the sideof sexual minorities, but it ultimately aims at reinforcing normative familyvalues.”

Recognizingthe often-rigid perceptions of the international LGBT Movement of what beinggay should be, that is, a way ofreproducing conventional notions of family values and social respectability,Karen Pinholt has intended to build an agenda that “(…) makes sure thateveryone who is LGBT can be that in exactly the way they want to be. You havethe right as a person to define who you are and live that life, and othersshould not limit you. That also means that as an LGBT movement, I can't tellother people how to be gay or that they are being gay in a wrong way. The GayMovement, in an attempt to find the gay identity, which is an important quest,has been moving on so fast that it has lost a lot of people. Some feel thatbeing on the back of a truck in a Pride Parade wearing next to nothing anddancing to disco music is a normal way to be gay. Whereas others think thatgetting married and getting 2.3 kids, or whatever is the average, is a normalway to be gay, because you are supposed to be part of the gay culture. Myobjection is to both. I think that we should work towards making it possible tobe gay exactly in the way you are gay, and to recognize that there are gays inall sectors of Norwegian society. There is no right or wrong way to be gay.There is only one thing that is wrong, and that is living a life you don't wantto live.”

↑Top

Ryan Conrad, Gay Marriage Will Cure AIDS, 2009

Ryan Conrad, Gay Marriage Will Cure AIDS, 2009

How Did We Get Here? The Same-Sex Marriage Debate

One ofthe central issues in the struggle between LGBT rights activism and queerthinkers and activists is same-sex marriage. The assimilationist character ofsame-sex marriage, condemned by queer activists and theorists, clashes with theemancipatory consequences granted to this legislation by rights activists, whosee in this law the definite step to gain full citizenship and equality.

ToneHellesund offers a chronology and assessment of this subject in Norway: “(…)After the period of focusing on visibility, gaining individual rights, andanti-discrimination laws, the work for partnership or marriage rights startedin the late 1980s. That has basically been the focus since then, the right tomarry. You can see that in many different ways. You could see it as areflection of the political climate of these decades: To focus on family valuesand respectability; on homosexuals being good, respectable and family orientedcitizens has been a very strategic and wise way of framing the cause. What hasbeen interesting is that the critique of the nuclear family and marriage, thosekinds of debates that were present in the 1970s disappeared from the publicagenda in the 1990s and the 2000s. There have been very few opposing voices inthe public. Although many of us have been critical of the family and therespectability orientation of the Norwegian Movement, many of us still agreethat to gain marriage rights has been an important step in the achievement ofcitizenship rights. Achieving the ‘Gender Equal Marriage Law’ in 2009 was kindof the final victory in regard to gaining full citizenship rights as queers inNorway. Despite the fact that many of us want to abolish marriage, we can stillsee that the right to marry has been an important step.”

One ofthe most compelling arguments in favor of same-sex marriage is the economic andinstitutional protection it might provide. Arnfinn Andersen, sociologist at theGender Research Institute at the University of Oslo believes that “(…) the struggle to get the samerights as heterosexual married people in this country was a way to get formalcitizenship, not only as it pertains to the law, but also as a way ofrecognizing our status as citizens in equal terms. I would say that the idea ofmarriage was a good platform to make Norwegians aware of our inequality becauseeverything in the social democratic society is organized around marriage:Pension systems, the rights you have when you have a baby, etc.”

Colombian political philospherMaría Mercedes Gómez offers an interesting perspective regarding the practicalconsequences of political stances when she says: “(…) It is much easier to saythat one does not agree with gay marriage because it repeats the traditionalpattern if one does not need health insurance, or protecting one’s children, ora residency visa. I always take into account what the scope of my politicalstance is at every moment, and what I can do to make sure that my politicalstance does not repeat or generate a form of injustice. Marriage generates a series of individualrights that are valid and necessary for people who do not have otherprivileges, and in that sense I think the option must exist. The consequencemay be that instead of undergoing a radical transformation, society will movealong lines that will continue to be unfair for many: for example, havingaccess to certain individual rights only through marriage. But since the space forradical transformation does not seem to be a possibility in the short term, Ithink that one must work strategically so that the people who want and needthis right may exercise it.”

Criticsof this legal strategy coincide on several arguments. For example, some supportthe feminist perspective that judges marriage as a patriarchal and repressiveinstitution. Esteban Restrepo, Professor of Law at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, asks: “(…) Why consider thatthe core of LGBT movement has to be the family issue? That is a mistake,firstly because we want to colonize the most oppressive institution, the one inwhich people have been more oppressed, traditionally. How is it possible thatif women have criticized for years the pattern of traditional family, we shouldwish to conquer marriage, that profoundly alienating and subordinatinginstitution? Then comes the question of normalization. The sector of activismthat has promoted the family issue is that liberal sector within the gaycommunity, which says; we are equal, we are not a threat, the only thing thatrenders us different from you is that we like persons of the same sex, but thatis restrained to the bedroom. As for the rest, we are like everyone else; wedon’t rape children or kill them. Might it not be that a long period ofsubordination creates a series of different cultures that are important topreserve, and that it would be an obvious mistake to lose? The monogamousdynamics will turn against the gay community itself or against the LGBTcommunity: Before, they did not allow us to get married; now the ideal thing isto be married. (…) The other issue is that the fact that same sex couples areallowed to get married and may adopt children does not imply that homophobia isover, because homophobia exists in people’s minds; homophobia is a prejudice,and prejudices are lodged in a very complex way in people’s minds, ineducational processes, in processes of basic socialization, at school, at home.To transform this, the Law has a minimal potential; it may raise the issue, itmay show a hidden social phenomenon, it may normalize it in the sense that itbegins to refer to the situation of many persons as an issue of politicalconcern, it may lead to self-questionings, but transformations are alwaysfollowed — and this has been shown in the context of the United States — by ahomophobic backlash. The homophobic forces within society resist. This occursin every sphere: When in 1954 the United States Supreme Court prohibited racialsegregation in schools, George Wallace, the governor of Alabama said: ‘I won’tcomply, I simply won’t comply; here our cultural life is based on theseparation of white and black persons, the United States Supreme Court ofJustice cannot come and tell me that I have to accept blacks in my children’sschool; I’m not going to do it.’ Why wouldn’t the same thing happen in anissue, homosexuality, which is linked to one of the greatest anxieties inWestern culture?”

ForAmerican radical queer activist Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, “(…) the messageof assimilation is the ‘We’re just like you’ mentality. When gay people say:‘We are just like straight people, we have no differences, except for who wemight want to have sex with.’ Marriage, military inclusion, adoption, ordinationto the priesthood and hate crimes legislation have become the corner stones ofgay assimilation. As queers we grew up in a world that basically wanted us todie or disappear. I think we shouldn’t grow up and want to become part of thatsame world and change nothing. The issue of gays in the military is the mostobvious. Instead of saying we want to be part of the military, we should besaying that the U.S. is responsible for more violence in the world than anyother country, bombing, terrorizing, plundering indigenous resources, andestablishing corporate control everywhere. We should be saying that we need toend the military, which is a dominant institution of imperial, colonial andgenocidal violence. I would say the majority of us grew up in the ruins ofmarriage. Why are we now saying that is what we want? What does marriage mean?For decades, queers had been finding ways to live and love outside of marriage,and with the ‘assimilationist agenda,’ it is all thrown in the trash.”

RyanConrad, American queer activist and founding member of the collective Against Equality delivers “ (…) amaterialist class critique to actually talk about marriage, to wipe away thisgloss of affect that portrays marriage as being about love and family, when itis actually a social contract between two people and the state and thetransfers of property, power and money between them. I think it is really hardfor people to step back from this sheen that has been put over marriage. Gayand lesbian activists have been digging up this rhetoric of affect and love,questioning how love can be outlawed, and it is actually not what everyone istalking about but a distraction from actually talking about how sexual identitydecides whether people live or die, have access to healthcare or not, can moveacross boarders, and access jobs. People aren’t talking about that piece. Theclass critique is huge for me and comes from an urban/rural critique as well.Not to suggest that there aren’t poor people in urban settings, but in Maine inparticular rural equals poverty. For me there is always a critique of urbangays with more money than the rest of us setting the agenda while peopleoutside of major urban centers don’t have access to any resources and are mostat risk for poverty and HIV. It is pretty ridiculous how urban-centric theconversation has become, something which is part of the class critique aswell.”

Meanwhile,Colombian lawyer and activist Germán Rincón focuses on the assimilationistoutcomes of same-sex marriage. “(…) In legal terms we have a second-classcitizenship, not a fifth-class any longer, but a second-class one. We have madea lot of progress, but from a social perspective we are far behind and at thismoment there is a wave of conservatism. Our homosexual life was undercover; nowthat we have entered the public life, and are legitimized as individuals and ascouples, we have become part of the heterosexual antiseptic, antibacterial little model. Only couples, only withone person, in what conditions yes, in what conditions no, all that regulatedmodel. People say ‘now we can’t be promiscuous because we are legal’ and Ithink that is a terrible loss; there are people who wonder: Who got us intothis? There are gay persons who disagree, especially with regard to the propertyrights issue, because they believe that if they take a young boy in, in a weekhe will take away from them half of their patrimony. This has generated aterrible impact.”

Inaddition, the devaluation of different ways of being in the world and the exclusionof diverse vital experiences are regrettable outcomes of demanding inclusion inthis normative model. Germán Rincón thinks that “(…) in Colombia, same sexcouples were violently pulled out of the closet, whether they liked it or not.(…) That hegemonic model has made us lose our underground status, which hadwonderful advantages. We have to begin talking about discourses other than thehegemonic model; I have strongly positioned the question of triples, not ofcouples but of triples, the relationships between three persons on theaffective, the erotic, the genital, and the family plane. It is the issue ofthe social family and not the biological one; the construction of family basedon the social and not the biological relations. From an academic point of view,we have to start delivering the discourse, in the social movement we have todeliver the discourse. In Colombia we have made progress; in the issue ofpensions, jurisprudence has established that if for instance, a man dies, twowomen receive pensions. We are waiting for the same to happen when a gay dies,that the two lovers receive pensions and to extend this further, to moveforward along those lines.”

EllenMortensen has similar concerns: “(…) Some of us have voiced critiques of thetendency within the gay community to go ‘straight.’ Not to choose straightpartners, but to live straight lives. Whereas if you take people like JudithHalberstam, who talks for another form of temporality and another form ofunderstanding of location, you see that there are certain ways in which the gayand lesbian community has a history of greater freedom when it comes to sexualpractices and to individual life paths that are not necessarily conforming togeneral values in society; respectable and bourgeois values of conduct. Youhave people like Leo Bersani, who wants to be a ‘homo.’ He doesn't want tobecome a housebroken general citizen, but one that embraces his own liberty asa life project.”

For Franklin Gil Hernández, “(…) Marriage is abourgeois value. (…) Let us have adebate on marriage, which is an untouchable institution from a social point ofview. It is important to request it, but once it has been requested, there mustbe a debate on the institution. What types of relationships does it propose?Family is a very violent institution. Why defend an institution that isviolent? There are other ways of being together that may function well, andperhaps they are more tranquil, more fair.”

María Mercedes Gómez contributes to this lineof reasoning adding that “(…) the reforms generated by same-sex couplemarriages do not produce any changes in society; they consolidate a givenvalue; they reproduce the liberal model of marriage and family, and there isabsolutely no type of threat to what Butler has called the idea of ‘Nation,’which is actually jeopardized by adoption. Adoption renders what is happeningin Latin America evident: some statistics say that 20 percent of the familiesare traditional families; the rest are other kinds of families, not necessarilyhomoparental ones. They can be extensive families, or there can be two mothers,or two fathers, single mothers or fathers. Adoption would imply Statejustification for something that is already happening, and this generates anunspeakable anxiety, because what is at stake is the notion of social cohesion,the notion of ‘Nation,’ the notion of a country’s ‘identity.’”

From a different perspective American artcritic and AIDS activist Douglas Crimp explains that “(…) something of an enormous shift happened in the the wave of AIDS toward a conservative gay culturewhere issues like fighting for equal rights to marriage and to fight in themilitary took precedence over what I think of as a truly queer culture, whichis a culture that wants to change how we think about forms of human relationsin a much more general sense. I still feel very much what I learned from earlysecond wave feminism, which was the critique of marriage as an institution andhow marriage actually served governance as a way of managing the complexity ofrelations that are possible among people. (…) One of the greatest gains of thegay liberation movement and the general liberation movements around sexualityand gender was the possibility of rethinking all kinds of questions ofaffective relationships so that among gay men, for example, if you stopthinking about finding Mr. Right, finding a lover or finding a marriagepartner, and rather think about possibly sexualizing friendship, maintainingfriendly relations with people with whom you have had a romantic relationshipor having fuck buddies, then a whole proliferation of ways of connecting withothers opens up.”

“Sexualityshouldn’t be a way to prioritize people's lives,” affirms Arnfinn Andersen,but “ (…) you get benefits based onwhom you are having sex with, since you are legally recognized as a couple. Abetter way of organizing this would be based on the needs that people have whensharing a household. We have family relationships that are more complex, but weare supporting only one type of structure: Marriage. Should we replicate theheterosexual model?”

Photo: Carlos Motta

Photo: Carlos Motta

Defying Assimilation: Beyond the LGBT Agenda

Several theoretical andideological perspectives support the opposition to the equality framework andto the mainstream LGTB Movement’s mission, based on the search for formalequality. Queer activists and theorists strongly object to this politics due tothe failure of this framework to achieve substantial equality and theassimilationist consequences that it entails. Others, representing the leftside of the political spectrum, base their objections on the existing andextreme social inequalities this model is unable to modify. This rejection alsocomes from those who believe that gay and lesbian organizations have lost theirpurpose, are committed to simplistic and objectionable motivations, and havebeen absorbed by the status quo.

Critical and Affective Difference

Thefirst line of reasoning of those who resist to be assimilated is to emphasizeevery trait, attribute, and quality that makes them different. Some do thisfrom a personal and a very determined viewpoint, as Norwegian lesbian pioneerKaren-Christine Friele who, having worked for several decades as leader of The Norwegian LGBT Association to achieve legal and formal equality, affirms: “(…) Even if I am as old as 75, I havealways enjoyed what you call diversity. I have never presented us as ‘we are asgood as you’ or ‘we are just like you,’ because we are not. I don't know howheterosexuals are, I only know how we are. I think it is stupid to do sobecause the point of this all is to accept that we are different, that we areunique, that we represent a color, (...) we are different.” In a similar vein,American sex therapist and intersex activist Dr. Tiger Howard Devore, declares:“(…) We are gender different: we are not equal. I don’t want to be likeheterosexuals ever. That is the last thing; otherwise I would have been aheterosexual… as if I had a choice! I don’t want to have the rights thatheterosexuals have, I want to have the rights that other human beings have. Weare different, but we are not different meaning that we should be subjugated,separated, destroyed, discriminated against or the objects of prejudice, noneof that. We are good human beings and rights have to be extended to all humanbeings, not just heterosexuals.”

Why would “ (…) we want our individualityrecognized within the existent structure rather than asserting our differenceand doing our own thing?” wonders Ryan Conrad. “Why seek affirmation fromthe thing you think is messed up in the first place? That shift has definitelyhappened since the late 1990s when I was in high school and it seems now it isa desperate push for affirmation and inclusion.”

Dr.Tiger Howard Devore further insists: “We are different, we are going to bedifferent, we are going to look different, we are going to feel differently, weare going to sound differently, we are going to speak differently, we are goingto have different activities on the weekends. When we get together in thecorporate coffee lounge, we are going to talk about different stuff than ourheterosexual work mates who have kids in school, unless we have kids too. Thefact is that that difference is never going to go away. Saying that we areequal or that we are the same is silly. It is not going to happen that way.”

Norwegiantrans activist and sex therapist Esben Esther Pirelli Benestad’s personalexperience is: “I do not provoke people and people are not provoked by thosewho are different. I think what is more provoking is our insecurity: When yousay ‘excuse me’ or ‘I am so sorry but I am different.’ That’s much moreprovoking than saying ‘I am different,’ or ‘I have something to tell you, I cansee something that you cannot see!’ I think it is much better to promoteeuphoria. People are not disturbed by euphoria, but most people are disturbedby dysphoria.”

American lesbian artist andfeminist Harmony Hammond shares this perspective, but is concerned about thepossible indetermination of these ideas. “ (…) I have to say that Idon’t think equality and sameness are the same thing. I believein equality but not in sameness. Thediscussion about the politics of difference versus sameness has taken many different forms over the decades. Currently it is focused around the right tosame sex marriage. (…) A place where it gets problematic for me (…) is aroundthe whole notion of being ‘queer.’ I like the notion of “queerness” and a queeridentity as a fluid continuum of sexualities. But in the last few years, thenotion of “queer” has been co-opted. It has become so open that it underminesits radical potential.”

MattildaBernstein Sycamore upholds difference vindicating its accomplishments in regardto creative and original forms of inter-personal connections and relations,deploring the normalization of sexual practices and the disarticulation of theright to be different. “(…) When I identify as ‘queer,’ it is just not aboutbeing queer sexually, it is about being queer in every way: It is a way ofcreating alternatives to mainstream notions of love, who you fuck, what youlook like, how you eat, and how you live.”

Aproject of queering our understandingof affective relations is part of Arnfinn Andersen’s research, because theyoperate on different levels: “(…) A friendship is quite different from livingtogether as a couple, for example. I have been discussing how it is to be acouple and/or to be a friend since ideas of intimacy arise from both of theserelationships. You should be close to a friend, but you should also be close toyour partner. An idea of equality is a part of friendship but is also a part ofbeing a couple. This means that friendship has become a cohesive way toorganize social structures. People don’t loose the ground when their partnersleave because they have friends that are also very close to them. People buildstructures for their lives that make it safer and more secure. This is a way ofqueering the question of intimacy andto understand new forms of solidarity in the society. (…) It is more commontoday to say that you have had sex with a friend. There was a taboo around thatquestion. I think this shifts an understanding of sexuality as a division betweena friend and a partner. It could be other things, such as the way youunderstand yourself, your ideas in life, etc., that make distinctions betweensocial relationships.”

This expanded notion ofaffection within gay and queer cultures, which represented an alternative wayof loving in the past, largely got lost within contemporary political rhetoric.American novelist Edmund White reflects on the way the gaycommunity in the 1970s, “(…) looked down on monogamy and I think the gayleaders of the 1970s would be appalled to see how many gays now want to bemarried and monogamous. Pre-AIDS, the idea was to be free, overthrow theheterosexual model, and try to invent something new. Part of that was toseparate out the various functions that accumulated in a relationship with oneperson in heterosexual companionate marriage that, we thought, did not work. Itwas ending in divorce; it was a disaster. (…) We thought you should have ‘tricks’for one night stand for sex, ‘fuck buddies’ you would see on a regular basisfor sex, a ‘lover’ who might be somebody you would live and have a physicalrelationship with or sleep in the same bed and kiss, but maybe not have sex orjust occasionally, etc. I think a lot of gay life is still being lived thisway, but I think gays have become so prudish that they do not like to admit itanymore. We thought it was a positive experiment, I think AIDS changed allthat.”

Douglas Crimp would “(…) even say that one could have many more than threefigures. For example you could say there is one person you havevanilla sex with and another person you have S&M sex with. You couldproliferate it in so many ways. (…) That is exactly what marriage does, it becomesyou and me against the world instead of a much more communal sense of sex andfriendship. It is not simply about sex, although it is about an erotics offriendship, and sex is certainly central to it. I actually don’t think it ispossible to get every kind of sex you could want out of one person.”

Crimprecalls that “(…) in the 1970s the ethos of gay liberation was that you shouldnever cut yourself off from anything, like if you say you are just a top thenyou are denying the part of yourself that is a bottom or vice versa. If you sayyou are only interested in real men,you are denying a part of yourself that is interested in femininity. Of coursethat is a utopian rhetoric but there is a truth to it so far as that you don’treally know until you have tried it, maybe more than once even, or tried it inthe right circumstances. This is also about a kind of denial of theunconscious; the notion that you could actually know yourself and know yourdesire.”

Colombianqueer theorist and art historian Víctor Manuel Rodríguez points out that “(...)sexuality always de-stabilizes any ideas of hegemonic order, both individualand social. Because of my age I remember that BogotaÌ’s queer scene in the1980s permitted some forms of articulation and solidarity that were strictlyqueer in the sense that they were not circumscribed to the LGBT communityexclusively, but to all the ‘weird’ people who gathered together in public andprivate spaces and who shared the idea that we were not ‘normal.’ But ofcourse, today those scenarios of solidarity, of collective fight againstnormality are not there because there has been a proliferation of a gay popularculture: There are 140 gay pubs in BogotaÌ, for example, that guaranteesocialization spaces for some, and represent normalizing spaces that must beresisted, for others.”

“(…)I feel that the city hasalso been the subject of normalization practices,” continues Rodríguez, “(…)and that at present the proliferation of those things that we might term‘counter-cultural’ are somehow normalized. Things happen, but mostly in spacesthat have become normalized, that is, the normalization of gay life forces usto explore other spaces. These counter-cultural sexual expressions have somehowbecome relegated to a space in which one must pay to see.”

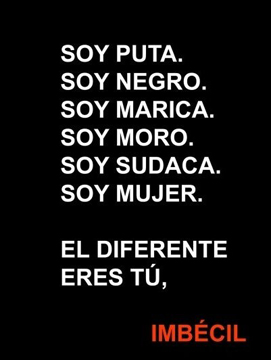

Spanish Socialist Party Anti-Discrimination Campaign, 2008

What is the Alternative? Social Justice.

A particularly sharp critique of the political driveof the mainstream LGTB Movement comes from the queer left, which identifiesracism, classism, militarism, and capitalism as being validated and legitimatedby the Movement in its attempt to conquer equality on its own terms. Isn’t aqueer agenda a suitable place to build an activism and politics of solidarity?

Ryan Conrad refers to this matter in his descriptionof the scope of the work of AgainstEquality: “(…) We are actually suggesting the idea of equality in the status quo and the systems andinstitutions that already exist were designed for a hetero-supremacist societythat is classist and racist. Maybe we should be investing our energy intotransformative ways of meeting our material and affective needs, dealing withharm and violence in our community and addressing whatever the ideas ofnationhood and national security are.”

“(…) When we talk about equality,” Conrad says, “(…)we are talking about this idea that we need to have equal stake in these hugelyproblematic, and I would say, deadly institutions. We are against that. Somepeople at events we have done say we are not against equality but for realequality, or against this sham of equality. I guess if that is how you needto frame it for yourself to get what we are saying, then that is right, we arefor radical equity. We are talkingabout economic justice and social justice on a broad scale and not justsingle-issue identity politics that none of us feel invested in.”

Similarly, American queer activist Kenyon Farrowexplains the origin of the organization Queersfor Economic Justice (QEJ), which he directed for five years. The name “(…)was intentionally chosen because the founders wanted to make sure we weretalking about these issues in terms of a queer politics and queer politicalends versus an LGBT lens. People sometimes use the term ‘queer’ to be allencompassing of different sexual orientations and gender identities. It is alsoabout actually naming the Lesbian and Gay Rights Movement as a product that isabout assimilating into what already exists in terms of a well-fed,well-scrubbed, middle class, bourgeoisie with white values, and the term‘queer’ being a politic that values the different ways in which the communityis gendered and made up of different people of color who use a range of otherterms that aren’t necessarily gay and lesbian terms. It also says it is okay tobe ‘deviant,’ that you do not have to assimilate to a more ‘normal’ model inorder to be accepted. ‘Economic Justice’ was chosen versus, say, ‘EconomicEmpowerment,’ or ‘Equality’ because QEJhas an anti-capitalist, and socialist lens in terms of how it sees economicjustice. We are not talking about ways in which to assimilate poor, low-income,or queer people into the dominant capitalist system or framework. We aretalking about wealth redistribution largely, and though we sometimes areworking very specifically on local policies that impact low-income LGBT peoplein order to make conditions better for negotiating some of the systems poorpeople have to negotiate, we also understand that it is morally objectionablethat people are poor in a country that has so much wealth, and we understandpoverty as systemic and institutionalized, rather than only about gettingpeople training to be able to access better jobs, or education. In a situationwhere the labor movement has been gutted in a lot of ways by the Right, what weare seeing in Wisconsin right now to us in terms of public workers losing, orthreatening to have their benefits cut while their right to collectivelybargain is being undermined, we see these as queer issues and central to how wesee the world.”

This resistance covers what Farrow calls “(…) thefour-pillar mainstream issues of the U.S. LGBT Movement including: Marriageequality, ‘Don't Ask Don't Tell,’ hate crimes inclusion, and the ‘EmployeeNon-Discrimination Act.’ First of all, marriage equality is an issue thatprimarily benefits upper class, wealthy, often white gays and lesbians who haveproperty or health insurance that they want to give their partner. If you are apoor queer with no health insurance or no job to speak of, and certainly noproperty, marriage as the singular issue in the way that it has framed as thepanacea for all that ills the LGBT community doesn’t work. We know many poorstraight people who are married for whom marriage did not bring about any majoreconomic shifts. We also see that kind of marriage equality movement tied to aconservative, and neo-conservative agenda around privatization, so that thestate itself can take less responsibility for helping people through differentkinds of social safety net programs. If everybody is supposed to be married andall of your social and economic needs are taken care of in your home then thestate owes you nothing. This is what we are seeing in Wisconsin with thepension debate, where a neo conservative movement is advancing that agenda, sowe are opposed to marriage on those standpoints.”

Farrow goes on to assert that “(…) we are also opposedto dropping the ban on gays in the military and advocating for gay inclusion inthe military because of the impact of the military industrial complex on theU.S. budgets, where about half of the U.S. budget comes down to militaryspending, and can be cut from major portions of how much money is available tohelp people with health care and a range of other needs. We are also opposed towhat the military and U.S. war machine does in other countries. Supportinghuman rights of gays and lesbians in the U.S. does not make any sense alongsidebeing able and kill, maim, and destroy gays and lesbians in Iraq, Afghanistan,Somalia, and the many places where the U.S. is doing all kinds of imperialistmilitary operations. This is similar to our position toward hate crimelegislation in terms of expanding the prison system in the U.S., which isalready the largest the world has ever seen in human civilization and primarilyimpacts people of color, including queer people who were locked up. The‘Employee Non-Discrimination Act,’ finally, is not a real plan towards economicjustice. It is not talking about livable wages or economic sustainability; itis merely a plan for working people to figure out some legal system for filingdiscrimination cases. We see, in terms of race, religion, or gender thatdiscrimination cases are actually quite difficult to win and we are opposed tothe mainstream movement.”

Franklin Gil Hernández refers to the limited politicalscope of the Movement in terms of social classes. “(…) The LGBT Movement has aclass bias and it is important to bear this in mind. It is a middle-classmovement and this is not by chance. It happens not only in Colombia, but alsoin all parts of the world, because there is an organization related toconsumption. Gay neighborhoods, I believe everywhere in the world, are locatedin the most bourgeois districts in the city; here it can be found in Chapinero.The question is, what benefits do people from the popular sectors obtain fromwhat has been achieved, for example, in BogotaÌ, for it is a very unequal citywith much segregation by class. Here poor people are far and isolated, and onewonders, if public policies are aimed at educated middle-class persons who arefamiliar with up-to-date information, who are politicized, what happens withthose people from the neighborhoods where, in addition to the rest, there arearmed groups.”

According to Diana Navarro, in Colombia “(…) publicpolicies have taken care of fragmenting populations, there isn’t a real socialarticulation, and that leads to every person being concerned with their ownsmall interests instead of practicing the solidarity that would be expected forthe whole of Colombian society to have access to the exercise of their rights.”

Activist and member of Solidarity for LGBT HumanRights of Korea, Jeongyolsays: “(…) The main preceptsof our organization are action and solidarity. (…) For example, at an anti-wardemonstration, we understand that (…) protesting war as an LGBT means much morethan protesting solely for political reasons. (…) We think it is important toshow solidarity to non-LGBT subjects as well, and we try to do that as much aspossible. We take part in collective actions, campaigns and rallies that treatdifferent subjects, to let everyone know that we are there, that we are one ofthem. We hope that when our members confront an obstacle, those who seek socialchange will come and support us as we support them. (…) In 2003, one ofour teen members committed suicide. At that time we were participating in theanti-Iraq War demonstrations, and he was with us all the time. After hissuicide, we spoke of him at a demonstration, about the situation that drovethis young person, deserted by his family and school, to kill himself.Protesting war and sexual minority discrimination may seem like two separateproblems, but they are not. When we organized a memorial ceremony for him,among the people that came were those who we met at the anti-war rally, morethan 300 of them! So many people came that there wasn't enough space foreverybody. We mourned together and encouraged each other. This makes me believethat those who we communicate with now will someday show solidarity to us.”

Building networks of critical solidarity is alsoimportant for CHOI Hyun-sook: “(…) Capitalism is thesystem that reinforces family values, heterosexualism, and patriarchy.Capitalism demands from families to constantly reproduce labor, something thatreinforces a culture of family values, which in our context equals amale-centered patriarchy. The distinction between normal and abnormal accordingto family values is capitalism’s running dog. This is why left-wing partiesmeet with anti-capitalists. (…) Capitalism seems to be the dominant system inthe world, but it is also exposing its dark side, such as with the recentfinancial crisis. I believe that our actions are constantly making small holesin the capitalist system and that as these holes create a network, society willbecome a more just place. Sometimes the progress will be slow and dull andsometimes it will be revolutionary. We do not know yet which path to take, butwe know where we are heading.”

“People call us utopist,” confesses Ryan Conrad.“(…) But why be anything less? Why set low goals or limit your vision? Utopiais not a place we are going to get to; it is a process, a way of envisioning afuture. It is important not to lose that. People want to be pragmatic andidentify marriage as the winnable thing, but this seems ideologicallyridiculous to me. Why would you compromise a vision of the world you want tolive in for crumbs from a table you don’t want to sit at? I get frustrated withthis concept of gay pragmatism, like we just have to be pragmatic, and investin incremental change. Incremental change towards what? A world that sucks? Aworld that is totally classist, racist, and hetero-supremacist? I’m notworking towards that.”

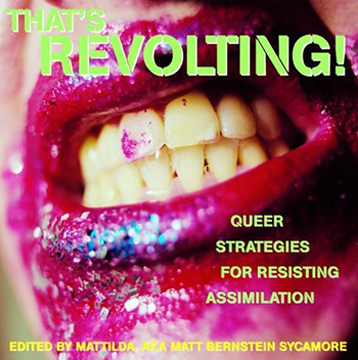

Cover of Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore's book

Cover of Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore's book

Back to the Margins: Surpassing the Status Quo

Those who believe that the LGBT Movement has lost itspath insightfully criticize it. They emphasize its deviations and errors. Theyspecially criticize the surrendering of the Movement to the status quo.

Critiques

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore believes that “(…)unfortunately gay liberation failed. It failed because the original goals, endof the Church, end of the State, end of the nuclear family, end of U.S.militarism, a broad agenda of sexual liberation, none of that has happened. Thereason it failed for me is because it turned inwards, it became part of themainstream and it became part of the institutional structures. I am notinterested in becoming part of those structures in any form. I don’t even wantmy own structure. I believe in building something on the margins, whatever thatmeans, and I am interested in infiltrating the mainstream media. I aminterested in creating our own media structures, I am interested in creatingradical alternatives, but not in terms of a narrow policy or legal framework. Ithink some of those legal battles are important, like the battle againstsodomy, the battle to be able to determine your gender identity, or the battleto put an end to the prison system. Becoming part of the National Gay Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF) and changing it orsomething, doesn’t do anything. It will still be an institution that doesnothing except take people’s money and speak to the center. I don’t want tospeak to the center. I am fine with speaking in the center and saying what Iwant.”

For Kenyon Farrow, “(…) economic justice issues andmassive imprisonment are so clearly based on race and class and the ability oropportunity to access material resources as well as the likelihood of your bodyand physical presence to be criminalized by the state. The national mainstreamequality movement in the LGBT population is not dealing with these issuesbecause they think in order to win the policy agenda they set, they have topresent the LGBT community as ‘normal’ as middle America. Meaning the communityand all of its promotion, advocacy, TV shows, sitcoms, all that has to presentas white, middle-class, and heteronormative as possible in order to getapproval from white, straight America. The movement isn't interested inchallenging larger structures of racism or economic deprivation because it seesvalue in assimilating the few gay and lesbians who can assimilate into white,middle-class, Christian, capitalist patriarchy. As Bell Hooks once said: ‘Ifthat is your goal, you will then only talk about poverty, wealth distribution,and racial justice in ways that are very tokenized.’”

Farrow is “(…) more interested in a debate around whatjustice really is. What is the vision? I do not think the LGBT Movement has avision for where it is going. I think it has made politically expedient choiceswithout actual vision for change or consideration of their policy choices andwhat these campaigns ultimately mean. I think this is reflected in the workitself. ‘Don’t Ask Don't Tell’ was dropped in some respects, mostly by courtorder and not advocacy work. With gay marriage, work done at the state levelresulted in thirty different state constitutions, so it was a colossal failureif you want to quantify the same sex marriage movement. It resulted in fierceopposition and worse policy for LGBT folks resulting in organizations that areswimming and do not know what to do next.”

Ryan Conrad’s assessment of the mainstream LGBTMovement is severe: “(…) The professionalization of gay and lesbian activistorganizations has a lot to do with it. Within the non-profit sector you answerto your funders and do what your funders want you to do: A hierarchy of peoplewith money still get to decide what happens. Equality Maine is a perfect example of this. They hosted a seriesof community dialogues and I actually went to one thinking, ‘Ugh, it’s Equality Maine, I’m not going to agreewith anything they have to say.’ I gave them the benefit of the doubt becauseit was a community dialogue, right? Wrong. It was a presentation on how theywere going to win gay marriage. They didn’t ask any questions; they had chartsshowing their strategies and their next steps if gay marriage passed in thereferendum. This isn’t a community dialogue. I kept thinking: ‘How did we gethere? We didn’t ask questions yet?’ This comes from super professionalizedorganizing, like the National Gay andLesbian Task Force (NGLTF), which gives you a $100,000 to work on gaymarriage. Gay and Lesbian Advocates andDefenders (GLAD) based in Boston, applied for grants from Maine Community Foundations Equity Fundto do gay marriage advocacy in Maine. So, people from Boston were coming toMaine and instead of listening and asking people what they wanted, out-of-stateorganizations began to zap local resources to do what they wanted. That is whatcontinues to happen. I think it is because of the non-profit industrialcomplex, where career activists answer to a group of upper class gay fundersthat want to consolidate power privilege and property through this thing wecall marriage.”

Sarah Schulman believes that “(…) there is an incredible fear, (…) I see it in everyfield. This is a time of incredible conformity and everyone, including teachersand writers, whatever their role, are terrified about making power structuresover them uncomfortable. They fear losing access, money, and respect.Everything is run by fear so people are afraid of alienating the powers that beand trying interesting new things because they are afraid someone is going tolook down on them and they will no longer be invited to the party.”

Schulman goes on to confess: “(…) I am afraid too. I amfrightened all the time, but I do not let the fears determine mybehavior. How I act and whether or not I am afraid are two separatethings in my process. I think questions such as, is this doable, reasonable,and morally sound? What are the consequences going to be when I do this?I know I will make some people mad but can I actually achieve somethingpositive? If I think I can be effective, I allow myself to feel afraid. Theproblem is when people act because they are afraid. These two things need to beseparated. It is okay to feel uncomfortable. If you are going to createanything worthy, you are going to feel uncomfortable and other people are goingto make you feel uncomfortable, and that has to be accepted as part of life. Ifyou want to feel safe all the time, you will never be able to do anything. (…) Itis very hard to change institutions. That is why we build alternativeinstitutions.”

*

Gay Shame marching against the war machine in SF, 2003. Source: http://www.gayshamesf.org/images.html

Gay Shame marching against the war machine in SF, 2003. Source: http://www.gayshamesf.org/images.html

Action

Queeractivists stand against hegemonic power and propose alternatives, build plansof action and construct agendas designed by and for marginalized people.Decentralizing power by speaking from “the margins” to “the margins” is a wayof tackling the Movement’s failures, but more importantly, of meeting theurgent needs of underrepresented communities.

Action and education arestrategies to surpass fear. Kenyon Farrow provides an example of the type ofwork developed at Queers for EconomicJustice where “(…) to combat the challenges we face in respect tohomelessness, we work specifically in the adult shelter system in New YorkCity. (…) First wetrain a team of facilitators who run support groups in the adult shelter systemin New York City. In addition to doing those trainings, we hold ‘Train theTrainers’ workshops, to train members of the community to provide support.Being homeless, you are so far removed from generally being able to participatein certain kinds of places and institutions in society, but also being queerbecause so much of the LGBT infrastructure is based in places of commerce suchas bars and clubs, gay coffee shops, bookshops, and restaurants. (…) Folks get marginalized so actually being in the shelter itselfprovides a space to build some level of community and support within theshelter as well as help others connect to different kinds of service oradvocacy so that they can either get out of the shelter system and get housingor get access to the kind of welfare and public assistance benefits that willhelp stabilize their income. We also begin to organize these folks to be ableto challenge the actual shelter based on issues that are relevant to allhomeless people, whether it is around conditions in a particular shelter suchas food or security guards targeting queer folks, or other folks in theshelter. This work ends up informing our citywide campaigns around the sheltersystem.”

Similarly,Ryan Conrad is engaged with the organization Outright L/A in Maine, an LGBTQ youth drop-in center that is openonce a week, where “(…) we do outreach programs training service providers liketeachers and healthcare practitioners to create safe and affirming environmentsfor queer and trans youth. Much of the work I do involves directly working withqueer and trans youth, mostly kids living in poverty in small towns andCatholic environments.” Additionally, Ryan lives “(…) in a queer collectivehouse in my town in Maine. (…) It has become a queer beacon safe house spacewhere we hold social events and have film showings, dance parties, and somelecture style stuff, but primarily cultural and social queer events in a townthat doesn’t have a queer meeting point, where there is no gay bar.”

Addressingthe lack of meeting and community spaces, Korean teen activist Jinki speaksabout her motivations to start Rateen:“(…) Even in Seoul there is no decent place where sexual minority teens can gettogether, and it is almost impossible even to meet someone like you in thelocal areas. So there was practically no base that our culture or activismcould stem from. The existing online communities mostly focus on meeting peopleand dating; after realizing my sexual orientation, I knew these groups couldn'tsolve my issues. (…) All I ever needed was someone telling me ‘Yeah,you're okay the way you are.’ But there was no place that could give me suchconsolation, so I formed Rateen.” Jinki goeson to explain that “(…) Rateen differsfrom the existing communities in two aspects: First, everything is organizedand run solely by teenagers; whatever orientation, whether you are lesbian,gay, transgender or anything else, we all gather as one; and secondly, weprovide shelter for sexual minority teens so that we can share our thoughts anddevelop our own culture.” At Rateenmembers “(…) pay the basic expenses out of our pockets. We never receiveparticipation fees for the seminar; they are held in public meeting rooms andare offered for free.” Rateen is notonly an online community, “(…) we meet off-line too. Once a month we doseminars on sexual orientation theories and social issues. And every August15th (Independence Day of Korea) we hold an (…) annual event, we do a lot ofthings: Queer film screenings, open counseling, lectures and recreationalprograms. People get to know each other and exchange information.”