We are seeing the Right wing politicize the question of representation yet again, because fundamentally it is their agenda. The Right, as all ideologues claim, wants to supplant a notion of a pluralistic democracy with an idea of a singular vision dominated exclusively by their perspective. They want to supplant discourse with abject props and look away from precedence, back to a realm of surety in which their particular ethnic grouping was unquestionably dominant. That vision of America is, thank god, dead except within the ideological Right, but they are doing their best to use the politics of representation to weepily bring us back to small town America and its fictive constructs…

Jonathan D. Katz

Download interview in PDF format ![]()

An Interview with Jonathan D. Katz

February 8, 2011

New York City

Jonathan D. Katz: My name is Jonathan Katz. I have begun to curate what I think will be a series of national exhibitions attempting to end the blacklist on sexuality that has been in play since 1989 with the censorship of the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery. I became an art historian that same year when I finished my graduate work and it was a very rough time to begin a queer project. Several years after that I started an organization with several friends in San Francisco called Queer Nation. I was also involved with the Queer Caucus College Art Association, Lesbian Can Tell and the Harvey Milk Institute, all of which were queer non-profit education-based social change endeavors. My current project is the latest in this trajectory and the stage is a little more interesting now because it is not specifically a queer stage. My trajectory follows what I take to be a larger trajectory of queer politics in America, whereas I was once doing LGBTQ-specific political engagements, now I am seeking to articulate queerness within the most potent metaphors of dominant culture.

Carlos Motta: How do you queer American art history when the filter has been so dominantly heterosexual and perhaps one of silence?

JK: It is such a strange moment in our field because recently the Museum of Modern Art bought David Wojnarowicz’s, “Fire in My Belly,” a video that was excised from my exhibition “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture” at the National Portrait Gallery. Somebody from The New York Times called to ask me what I thought of MoMa’s acquisition. The museum was never interested in my exhibition, in fact was not interested in doing anything queer at all. I would say there is a shortage of queer discursive frames, and until there is a greater acknowledgement of the discursive import of sexuality it will not matter how many works by queer artists museums buy. It is also the case that because of this reign of silence, we have actually falsified American art history.

For example, there was an exhibition on Robert Rauschenberg’s “Combines,” and in one of the combines there is a love letter from Jasper Johns to Rauschenberg. The catalog, unable to articulate the love letter, tells us it was created by Rauschenberg’s son Christopher, as an emblem of paternal -not erotic- love. Christopher would have been less than two at this time, and as he authored the essays, he wrote this to avoid any imputations. It has been very difficult, I have been thrown out of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Museum for raising questions about sexuality.

CM: Are you saying there has been a self-conscious effort to erase themes of sexuality from art history?

JK: Yes, and it is not just self-conscious, it is aggressively policed. When, for example, Rauschenberg did a retrospective in 1995, he was scheduled to give an address to an audience. I reviewed it for The Village Voice and secured press credentials to attend, knowing I would not otherwise be allowed in. I got my press card and I am sitting down in the room when someone comes up to me and says: “Mr. Katz, please come with the aid of the security guard.” I knew the curator of the exhibition, Susan, so I called her and asked what was going on. She told me to submit my questions to her in writing 48-hours in advance, and if they were approved they would be passed on to Rauschenberg.

CM: Is this policing institutionally based or is it also by the artist?

JK: I think it is done in the name of the artist, but there is a beautiful convergence between the ascription of the artist’s ideas or investments, and those of the museum. The museum would not be participating in this policing if it did not also serve their purposes and it clearly does.

Thomas Eakins, Swimming Hole, 1884

Source: http://www.askart.com/askart/e/thomas_cowperthwaite_eakins/thomas_cowperthwaite_eakins.aspx

CM: How does your project begin? How do you start to think of queering American art history? Where does it start?

JK: I think one has to begin by getting rid of the idea that gay is a biographical category. I certainly do talk about gay artists, but I also talk about artists like Thomas Eakins. One has to recognize, the genius of being an art-historian, as opposed to a literary scholar, is that pictures can say things written materials cannot. Words carry political significance and legal weight but pictures can evade things. You can notice things in a picture or not. You can make something available to one audience, while excluding another. Pictures have the ability to articulate a scene in a number of different social and political registers and so we have this extraordinary archive of queer American history and queer art history that we never thought to look at precisely because we have never approached it this way.

CM: That stands from what I would call the “tyranny of American morality” in a sense. Is it a parallel narrative that conditions the way we think of art?

JK: It is one of several things at work here. People say it is the artists but Eakins has been dead for a long time and when The Metropolitan Museum did an Eakins’ retrospective, 25 years of queer studies scholarship was erased from exhibition wall labels, the catalog, and the bibliography in the back of the catalog. In that sense it is an aggressive wiping away, coming from several things but I do not actually think American moral prescriptions are at the top of the list.

I think what is at the top of the list is money. We once had an idea of the museum as in the service of the public interest and in some sense trying to elevate the public through exposure to culture. However patronizing that 19th century model, what has happened in museums over the last 25 years is the way in which they have become an extension of private capital. We see this most readily in the case of the L.A. MOCA when after financial problems; a major donor dictates the terms under which the museum will reinvigorate itself by selecting a new director who is an art dealer. The process becomes full circle because collectors are telling museums to hire dealers making current directors nervous, and that is because we effectively have high volume commodities. Essentially the focus of our forms of inquiry shifts to allow market forces to mitigate against the discussion of sexuality. Ellsworth Kelly told me once that if people found out he is queer, it would hurt the price of his work. Worry about prices and what the imputation of his queerness would do to the price of an artwork, tells you a little something.

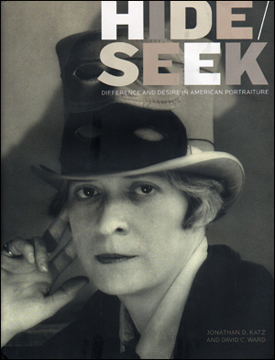

Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, catalog cover

Source: http://www.specificobject.com/objects/info.cfm?inventory_id=17591&object_id=15579&page=1&options=

CM: Is the fear that a hint of sexual orientation in the work would demystify pre-modern and modern ideas that art is based on technical mastery as opposed to having to do with the body?

JK: I think in part, but also because one wants to understand works of art as created for the viewer. There is a presumption and an investment by art history in this idea that the work of art can be decoded or read by the viewer or by anybody. That is why modern art is always subject to certain forms of popular social sanction; we expect the work will simply deliver, it is supposed to mean to me without regard to what I know or how much of art history I am invested in. In a process where the work of art is essentially supposed to be transparently available to its viewer, queerness is something that removes, restructures and reorients the work so that suddenly it is not about the viewer.

I also want to stress that art has been held hostage by a culture war that is not ultimately interested in art. What happened with my exhibition “Hide/Seek” is not really about art at all. In some broader sense it is not even about queerness at all, it is about raw American politics and feeding us as raw meat to their minions. That has been a strategy engaged in since before McCarthyism, the right wing divide and concur strategy. The best enemy is an enemy within. This allows the right wing to solidify their authority by policing a group from inside one’s own sphere and that is what they are trying to do, they are trying to police. There will be show trials and they will make comments about us that feed their base of supporters, which are doubtlessly noticed yet even the most progressive folks on Capitol Hill haven’t raised an objection or come to the defense of art. You think this argument would be handed to them on a silver platter, my god the fucking Republican Congress reads the Constitution of the United States at the opening of the first Republican Congress and then abrogates it by talking about the end of freedom of speech and the end of a separation of Church and State, and in the context of my exhibition and nobody says a word.

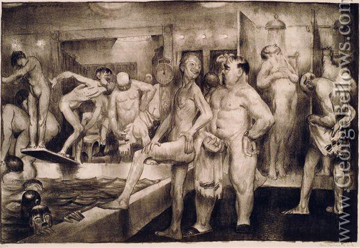

George Bellows, Shower Bath, First State, 1917

Source: http://www.georgebellows.com/artwork/George-Bellows-142

CM: Can you touch briefly on the chapters in which you divided the exhibition and identify what you would consider the most important issues concerning these periods, perhaps by exemplifying with the work of one or two artists?

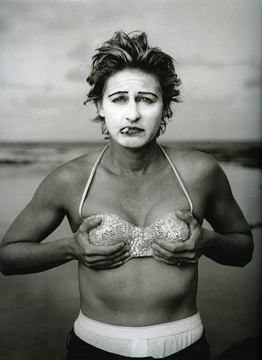

JK: The show begins with “Before Difference” and what I really wanted to do with the exhibition as a whole was abrogate the arrogance of the present, which is the assumption that the past looks like us, that if we look hard enough we will see ourselves reflected somewhere back there. Of course the past is very different. Showing people something they cannot believe existed in 1915 is what I sought to do in my exhibition. One of the earliest works I take as a kind of Rosetta stone of the exhibition is a print called “Shower Bath, First State” from 1917 by George Bellows, who to our knowledge was never involved with men. This work places a homoerotic encounter front and center; it has a stereotypical queen, thrusting his buttocks back looking lasciviously over his shoulder at a much butcher man with a towel-covered erection. It is right in the middle, there is no avoiding this scene of a bathhouse with a number of naked men. I looked at this wondering why we don’t see mass marketed images of same sex desire today, when in 1917 this print was made into an edition three different times and was sold out each time. It was not made as a painting would be for one collector who was sort of predisposed to like this material; it was created for the open market.

That began to get me thinking about what that world looked like. Sexual desire, as we understand it today is premised upon the gender of the person with whom you are having sex. Your sexuality depends on the gender of your sexual partner. In the period of question it was, rather, the gender you took on in the sex act, so if you were behaving in accordance with the dictates of your gender, if you are a man and you are fucking, you could sleep with men all you wanted and would not be queer because you were behaving in accordance with your masculinity.

Of course the converse was equally true and the ramifications of this are profound because it suggests the degree to which one could not, as we would today, build a Chelsea, a gay ghetto, or a political movement. Forms of exclusive and essentializing identity were paradoxically unhelpful and unfruitful precisely because they led you away from the straight men that were the reason you were declaring yourself queer in the first place. Necessarily queer and straight culture were interwoven at that moment and an artist like Bellows who is interested in social margins, people of color, immigrants, and queers, would have depended on the fact that people recognized and had seen similar homoerotic encounters at the bathhouses. This was of course at a moment when many people bathed in public bathhouses any way, so there was a greater visibility and discursive presence to homosexuality in 1917 than in some respects there is today.

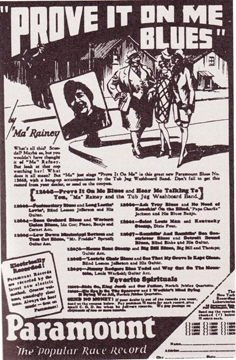

Adverstisement for Prove It On Me Blues by Ma Rainy, 1925

Source: http://www.outhistory.org/wiki/Ma_Rainey's_%22Prove_It_On_Me_Blues,%22_1928

CM: Because the category of homosexuality was not as sedimented as it is today?

JK: Absolutely. Again, only one person in that homoerotic dyad was a queer so you really did not have the notion of homosexuality. You had homosexual acts and you had inclinations, but what would two queers do together? They could not sleep together. I wanted to explore the degree to which America had not yet cleaved queerness away from its own self-definition; that queerness was part of America.

There is another image in the exhibition, an advertisement for a record called “Prove It On Me Blues” by Ma Rainy. Ma Rainy was widely known to be a lesbian, a butch, and in 1925 was arrested for holding an orgy at her apartment. Apparently the women were screaming too loud for her neighbors and the story goes that Ma Rainy, who was a large women, fell down the fire escape and got busted and three years later released this record. The lyrics are: “They say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me, all gotta prove it on me.” She goes on to say: “Yes it’s true I wear a collar and a tie, yes it’s true I don’t like men, yes it’s true.” In other words, she lists all the characteristics of lesbianism but she says: “But y’all gotta prove it on me.” The record advertisement shows Ma Rainy chatting up two very beautiful; stealth young black women while two cops are looking at Ma. She makes the whole incident that everybody knew, not just part of the process of the music, but she is using it literally to sell records in a way that Madonna would today. Again, it is a very different social world and I wanted to get people to understand how profoundly queerness was part of America once upon a time.

CM: Was there a discursive arena around this time that addressed issues of sexuality in relationship to art work?

JK: There was a discursive arena. There were queers, but it was not a good term. You would be arrested if you were queer, or if there was a police endeavor to run people up, but at the same time places like Bryant Park were widely, universally known to be gay cruising grounds in New York. Everybody knew about Bryant Park and occasionally, the police would ritually clean up Bryant Park and bust everybody, but it went back. The point I am trying to make is that in this period in which there was not yet a coherent or cohesive homosexual community or identity, there was concomitantly no desire to separate out the “homos” from the rest. Paradoxically this made for a world in which there was much greater acceptance of diversity and recognition of diversity on an individual basis than we would see today. People did not react strangely to the idea that there were queers among them.

CM: This paradox about politicizing sexuality can be seen when post-Stonewall many people that had been living in discrete lives were outed and made to believe they had never done anything to address issues of rights and sexual orientation, when in reality they were doing a lot by living their lives in open, but maybe not in political ways. It was after all a very different time.

JK: I am glad you are raising this because the next exhibition I am doing for the Leslie/Lohman Gay Art Foundation is actually called “Gay Politics Before Gay Identity.” It is an exhibition of the interior of the home of 96-year-old man, who is still alive, who was a ballet dancer, set designer and friend to a number of artists. If you walked into his home you would immediately think of it as a gay interior, with major art collections of the work of George Platt Lynes and Lincoln Kirstein and a ballet room with all the tokens of his ballet life.

I am doing this show because this guy wanted the interior of his home to reflect an identity that was not in evidence outside the door of his house. When he was home, the walls were him; outside the world was a very different place. It was very clear to anybody visiting that he was queen and he wanted it that way. This is the kind of gay politics we have not credited. He ran a cafe in World War II as an officer behind enemy lines in China called Mamma Greco’s. Mamma Greco was a large hairy Italian drag queen in World War II who was universally known by this nickname. These stories do not get told, of course not, we very rarely find our history reflected back to this.

Marsden Hartley, Painting No. 47, Berlin, 1914-1915

Source" http://hirshhorn.si.edu/visit/collection_object.asp?key=32&subkey=8184

CM: Let us move on to the next chapter of your exhibition, “Modernism.” Can you address how you provide a queer reading of the work made at the time?

JK: Modernism was in part about taking meaning out of accepted channels and notions of significance and finding new forms for signifying. Sexuality and modernism thus ran a parallel track. One of the artists credited with the development of abstraction in America was Marsden Hartley in 1914. We think of him as making the first abstract works when he was in fact making complex pictorial addresses to the memory of a partner who had died, Karl von Freyburg by embedding mages of Karl’s military status into the picture. This allowed Hartley to address Karl’s life and his love for Karl, without outing himself as being in love with a man whose nation would become an enemy during the First World War.

Modernism became one of those vocabularies that allowed forms of new address in which significance could teeter between pure formal play and something else and a number of artists took advantage of the possibilities of new formal play to embed or encode work with other kinds of meanings that were readable to a much smaller group. People find this very strange, this idea that painting or works of art can speak to different audiences at the same time, but we readily acknowledge that couples can have a private language that they use in public. One finds multiple competencies in reading works of art at different levels of audience, and artists played with that quite self-consciously. In fact, I think artists were much more aware of those different levels than we are today because real circumstances were associated with them. If you got caught sending a work in the mail that was read as a queer you could be in jail for it.

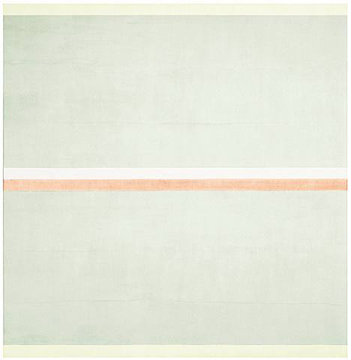

Agnes Martin, Above Called Gratitude, 2001

Source: http://therepublicofless.wordpress.com/2010/05/19/agnes-martin-artist/

CM: Can you speak about the reading you have done of Agnes Martin’s work in regard to this conversation because I think maybe it is a good example of what you are talking about.

JK: Sure. I have been trying to excavate the sexual enclave of abstraction because I felt that if queer studies was to have any real cultural traction, it had to be able to make sense not only of images of bodies and of bodies in various forms of communion, but to actually address the question of abstraction itself.

Martin is a very curious instance and in my exhibition, I have an example of her female nudes from the 1940s, where one of her lovers is represented. Martin aggressively tried to store all those early works but they survived because her lover kept them under the bed for many years after they broke up. When they finally entered the market, Martin was going to buy them to destroy them. The broader argument about Martin is that she was looking to suspend any idea of a given or naturalized category, be it gay, lesbian, painting, drawing, any singular or stable world in favor of a moment of eminence and pure becoming. In Martin’s work the grids make the work as vertical as it is horizontal, as painterly as it is linear, as stable as it is unstable. In other words, every single relationship one could find in her work cannot be locked down to a singular significance or value.

I wanted to think about queer investment; I think there is investment in creating a sphere in which there is a notion of becoming and valuelessness, at least a world in which stable values are no longer at work. The experience people have while looking at Martin’s work is often discussed as an unraveling; the work relays itself to you slowly layer by layer, and that process of recovering meaning in time is ultimately a moment of suspension from all the other categories of life that you are no longer aware of and all the other ways in which life is simply given to you. It is a moment of openness in a closed off, regulated world. Paradoxically I think that is the kind of liberation that Martin understood as queer, where our idea of queer liberation at the post Stonewall moment would have been to say: “I’m gay, I’m proud, that is my banner.” For somebody like Martin that would have been merely agreeing with a dominant idea of what to be gay or lesbian is and claiming that category for yourself. Better, she said, to eliminate categorization in its entirety.

CM: What would she have thought of this interpretation of her work? Would she have been okay with a queer reading of her art?

JK: No. Built as one of the irresolvable paradoxes of what I am trying to do is to give a lesbian reading to a form of art making that sought to evaporate the very category of difference or any stable notion of identity. That cuts to the core of the problem because I have always believed in the queer revolution, but I approach it like a post-Stonewall gay guy. I am interested in talking about sexuality, I am interested in talking about people who have not been forthcoming about their sexuality; outing people not because it is controversial to do so but because I think it reveals aspects and significances in their work that otherwise aren’t available.

Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg incorporate inter-pictorial conversations. Unless we can read those conversations we only get a part of what those paintings are about. Ultimately, I am interested in what queerness holds, which is that we finally achieve a world where we do not categorize people according to sexual differences, but I think the way to achieve queerness paradoxically is through the most rigorous engagement with gayness. By that I mean that the more one talks about the import of sexual difference, the less important sexual difference will become because it will eventually manifest, in so many different ways, commonality ahead of difference.

Annie Leibovitz, Ellen Degeneres, Kaui, Hawaii, 1997

Source: http://www.edgeboston.com/index.php?ch=news&sc=&sc3=&id=113583

CM: I often hear from people I have interviewed that the more you claim there is difference and the more you contribute to an idea of difference, the more you make the distinction between difference and sameness irreconcilable.

JK: We can look at Ellen DeGeneres coming out on television, which for me is a classic shift that reflects my point. There was nearly 8 months of build-up about Ellen DeGeneres’s sexuality and whether she would come out on television. Finally she signals that she is going to make a statement and everybody is wondering if she is going to say she is a lesbian, or bisexual. It was so tiring, then she said it, and everybody is relieved she finally claimed it. This was the first famous person to say they are queer on television. Currently, if you say you are queer on television, nobody gives a shit.

Glee, Modern Family, and other TV shows have created queer roles and nobody cares. What happened is that once we were able to get over the discursive recognition that there are queers on television we were able to think of course there are queers on television because there are queers everywhere.

CM: Is there a difference in accepting queer characters on television shows that are intended as entertainment in comparison to someone like Anderson Cooper, who is unofficially gay and in the closet, and would likely lose his job if he came out on television?

JK: I am not sure actually. I think that is Anderson Cooper’s fault. I think there would be “brouhaha” among assholes like Rush Limbaugh, but you would tell them to fuck off and you go on. As for Anderson Cooper, I mean, my god everybody knows! It is sort of the “Ricky Martin Syndrome,” like: “Ah! He finally said it.” I am not convinced of that distinction between the queer entertainer and the queer newscaster. In fact I think we have to start recognizing that what we are talking about is not knowledge and lack of knowledge, but knowledge and acknowledgement. Everybody knows so it is just a question of acknowledging and articulating what everybody already knows.

John Cage performing 4'33''

Source: http://artandzentoday.com/?p=132

CM: Returning to the chronology of the exhibition, I am interested in your reading of John Cage and contemporaries, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, and the recording of chants, silence and coding as strategic forms of resistance. Can you address this period and how you are reading these artists’ works?

JK: I wanted to mark out the degree to which it essentially made sense for a closeted gay man like John Cage to make silence the touch-work of his aesthetic. My thinking began around that problem because I thought how this is not the way the closet operates. If you are in the closet you want to be seamless. You do not want to be seen as hiding anything or being silent about something because the point of the silence of the closet is to ape perfectly dominant culture. Yet, John Cage is not aping dominant culture when he makes “Four Minutes, Thirty-Three Seconds,” his famous silent work. He is actually performing an act of silence and in this sense silence becomes an active engagement rather than a passive act. It becomes an engagement with the notion of silencing.

What I have tried to do with these readings is to expose the ways in which the works are not political according to our understanding of politics, but that the artists were discursively trying to make work that addressed the most general terms of their sexuality and their identity.

CM: That injects a reading of subjectivity in work that is traditionally presented as formal.

JK: Absolutely, this is one of the things that really get to me. There is a kind of policing action around the entire covert that says this work is purely formal. I would argue overwhelming predominant founding figures of this discourse are people for whom the articulation and not the real voice were deeply problematic, precisely because of homophobia. Let’s think about the social historical origins of something, which wants very much to claim that it has no social historical origins, but is merely recognition of a way works of art, operate. I am too much of a social historian to play that game and the paradoxical result is that when I talk about the social history of post-modern theory, I am often accused of being ignorant of post-modern theory because postmodern theory mitigates against the discussion of its own social historical origins. I do not care. Precisely because if we are to address the social origins of this, we will come to see how influential the particular politics around gay life were at that moment in its boundary. In fact I am teaching a course called “Post War, Post Modern” this semester, which is broadly a reading of exactly that moment and queerness as its motor force.

William Whyte, The Organization of Man, book cover

Source: http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/725027.The_Organization_Man

CM: What was happening in popular culture at the time in which these works of high art were being made and conceived? Was there a relationship between the work of Cage and the cabaret or other things that were happening outside the art institution?

JK: It is actually very interesting, there is not a relationship in formal terms at all, but there is a profound relationship, which turns on the denial of the authorial because this is a cultural moment that sees the rise of an entire, populate literature. One representative work is “The Organization Man” by William Whyte of 1956, a best selling work in which Whyte basically says the old model of the American was an inter-directed frontiersmen, somebody in contravention to receiving wisdom and reinvented himself, decided how he was going to live his life according to his own deeply internalized standards. White then says that the image of the American became supplanted by its organization. Somebody who achieves power within an organization and learns to mobilize power by a kind of repeated social camouflage so that they become one thing to their boss and another person to the employee below them. They learn to perform or mobilize multiple identities and this is evidenced across popular culture at this time. Needless to say, without roots in the Cold War itself there is this idea of multiple personalities, multiple faces, the man in the gray flannel suit, I could give you hundreds of examples. What this suggests is that at the very moment that popular culture is invested in the idea of an identity that is mobile and multiple and not singular so too, is post-modernism as seen with these early artists. We have a moment in which a queer subjectivity and a straight dominant subjectivity travelled a parallel track and that is really what I want to explore at this moment, why it makes it so interesting that queers long accustomed to domination knew best how to give it a formal language.

CM: Can we bring dance and Merce Cunningham into this conversation as a similar development or is there a space within dance as art that allows for opening an expression of the body differently?

JK: It depends. There was a reaction to Merce precisely because, as one of his dancers once put it to me: “I got tired of being meat on stage.” He was saying he wanted to be a person, to have subjectivity on stage, but early on Merce had a problem with the development of his “chance operations” in giving stage directions. He was uncertain as to how to tell a dancer which way to turn without authorizing the audience and the front of the stage, the way unproblematically we have traditionally set the center. Merce doesn’t want to have centers and he doesn’t want to establish lines of authority. How to instruct dancers to turn without making the audience the center? He came up with the idea that the center or forward was wherever the dancer was then facing, so different dancers had different forwards, different moments in the dance. It is a beautiful metaphor for what Merce was trying to do, but it is also a political allegory as so much of his work is. If there is no center then it is not possible to be at the margins and that is part of what this work is about.

Jess, The Mouse’s Tale, 1951/1954

Source: http://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/1321

CM: That is beautiful. What is the representation of Stonewall and this time in “Hide/Seek”?

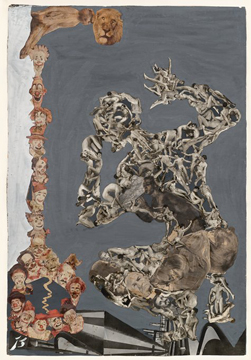

JK: We wanted to de-center the idea that something began in 1969 and instead make clear that in 1969 something achieved discursive form that had been coming together for almost 20 years. There is a series of works in the exhibition, two in particular that I will point out. One by Paul Cadmus and the other by California artist Jess that takes the earlier politics of the exhibition with its interwoven relationship between queer and straight, making for a clear kind of division, a boundary in emergence.

Jess for example in 1951, cuts out a series of nudes from strike magazines and makes a collage of an entire figure, which includes the nudes posing and the larger figure posing in a mirror. The mirror is made out of clowns’ heads and there is a noose at the bottom of the mirror. The work is called “The Mouse’s Tale” after Lewis Carroll’s poem of the same name. The noose literally ends with the last lines of poem: “No need for a trial, I’ll be the judge, I’ll be the jury, I’ll try the case, and I’ll sentence you to death.” Here Jess is very clearly outlining the world in which we find ourselves reflected and sentences us without any vestige of justice. That is a very different politics in 1951 from the 1917 painting by George Bellows.

Similarly in 1948, Paul Cadmus does a work called, “What I Believe,” which works to cleave gay from straight. In 1938, smelling the winds of war, E.M. Forster writes an essay called “What I Believe,” which asks how Western culture will survive the coming confrontation and what will happen to art, literature, and music stating he believes the high points of Western tradition will be preserved due to the good offices and aristocracy of the sensitive defining the elite not in a historical sense but rather as chosen through sensitivity. He states they know one another as they catch each other’s eye in the street and it becomes very clear what he is talking with this sensitive crew. Ten years later, after World War II and its mass destruction, Cadmus realizes a similar vision by creating a gay side to the picture, which is all about art and beauty. He puts all the people that he is lovers or friends with, Lincoln Kirstein, his lover Jared French, and E.M. Forster himself in one side of the painting and in the other side puts Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini reining destruction and death saying look how straight people kill Western civilization and queer people keep going. I find that really interesting because fifteen, twenty years earlier we were talking about one American life and now we are talking about these two communities each of which now have an essential social role. That was in 1948, Stonewall is in 1969, it is twenty-one years later that politics achieved a discursive profile with Stonewall that carves out these two communities.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Portfolio X, Self-Portrait, 1978

Source: http://phomul.canalblog.com/archives/mapplethorpe__robert/index.html

CM: What is the role of photography during and after Stonewall or the influence of documentary-based work? Do the type of documentary narratives that are created assert a different way of understanding sexuality?

JK: One of the interesting things about photography is its claim to indexicality, which offers a lot of room for political and social work and play to be exploited by artists of this period. It is also notable how early on many photographers, Mapplethorpe perhaps most notably, also used photography to force attention to things that people prefer not to see. I always think of Mapplethorpe as the great framer because so much of his photographs framed around something everybody knew existed, but preferred to advert their eyes from. What is interesting is the politics of claiming a particular perspective very quickly mutates into, and I have always struggled with a term for this, but I call it a “poetic post-modernism,” which different from expressive photography articulates a photographer’s personal perspective, á la Mapplethorpe who is very clearly articulating his culture, beliefs and values.

Artists that are appropriating the language of post-modernism, see the reality of appropriation and anti-authoriality, so it looks like they are not the authors of their own works, not making any political statement, there is nothing expressive. Yet if we look at those works, we find that they are curiously interested in appropriating earlier queer work. There are many different ways in which they are available to queer readings and this suggests an agreement with contemporary queer work that doesn’t want to claim gayness as the exclusive vector for reading or understanding the work, but it certainly doesn’t want to exclude it either, so it has a found a way to allow queerness to emerge alongside other frames of reference towards the interpretation of the work.

CM: In the case of Mapplethorpe queerness is one of its most essential readings.

JK: Absolutely. What Mapplethorpe does, in the hierarchy of significance of that work is elevates queerness. You can say a lot of things about the formal terms of the work and all of it is true, but you cannot leave behind the fact that its queerness quotient is very high. These other figures are interested in taking that quotient down but not to the point of closeting it. It is not towards closeting it I think; rather it is to bring other things up so that queerness is integrated into the work not as its raison d’etre, but as part of the work as it is part the artist and life.

Jim Hodges, No Between, 1996

Source: http://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/20917

CM: Who are these other figures?

JK: Jim Hodges is a good example of such a figure. He is doing more installation and painting than photography but he is, in some instances, riffing on the work of Felix Gonzalez Torres, creating works that allow richly, evocatively queer meaning and they play with the notion of handicraft, feminine coded work. He famously builds and sews together a gigantic curtain of plastic flowers, so it has the floral element, it has femininely coded structures and yet one can read it in queer terms as a dissident or one can see it as a pretty curtain made out of plastic flowers.

CM: I want to go back a few years to ask your perspective on the relationship between the feminist and sexual revolutions and the kind of art produced throughout the 1970s. Is this relationship something that is addressed in the exhibition?

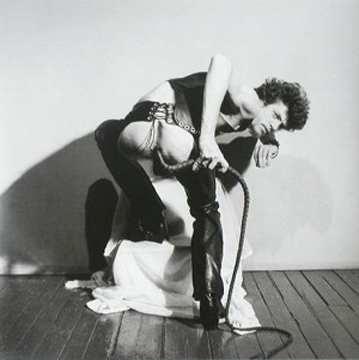

JK: I bring out work associated with lesbian separatism because I think we have rewritten a history of the queer movement that intentionally does not articulate the slightly embarrassing historical moment when women felt it necessary to exclude themselves from a male dominated society and create their own culture. Of course we fully recognize and celebrate male separatism with all sorts of different angles; universities in the United States were male separatists and Yale did not let women enroll until 1968. Male separatism of course is an unmarked category, yet female separatism we get very upset about. It is one of the things we tend not to talk about, yet, there were a number of photographers working out of a separatist idiom who wanted to make photography, including erotic photography that spoke about women’s relationships with women and the exclusion of men.

A section of the exhibition talks about this, but more broadly I think a lot of the work initially in the 1970s around feminism tended to be framed by critics like Douglas Crimp and Craig Owens in ways that minimized its social historicity. Sherrie Levine, for example, photographing historical works of photography and making those works her own is understood as engaging an act of appropriation in which her gender is of no significance. The fact that the artists she is re-photographing are men never enters the picture and gender remains abstract.

Cindy Sherman’s photography and Barbara Kruger’s political critiques are attempts to reengage a question of feminist critique, which queer male critics like Crimp and Owens, did not see. From Crimp comes a beautiful example of the shifts AIDS generated. Crimp comes to recognize that the very orthodox post modernist terms of his engagement, anti-authoriality, seriality, appropriation, losing the hand and the touch of the artist, is of course in perfect sync with a culture that doesn’t want to hear about queerness and AIDS makes him manifest the necessity of violating that orthodox post modernism and bringing back an idea of community, of culture, of history, of meaning, in its old sense of expressive intent, back into art.

AA Bronson, Felix, June 5, 1994

Source: http://slog.thestranger.com/slog/archives/2011/02/10/ab-so-fruit-ly-dan-savage-on-the-censored-smithsonian-show

CM: How is the period of the AIDS crisis represented in the exhibition?

JK: There are works by people like David Wojnarowicz, Felix Gonzalez Torres, Mapplethorpe, and a beautiful work by AA Bronson of his partner minutes after he had died. This work addresses precisely the politics that one wants to advert ones eyes from: The specter of death.

It was in 1987 that Reagan’s spokesperson said there was no evidence AIDS was spreading to the general population. I remember sitting at home wondering what that made me. That was the political frame, so you have AA Bronson doing this large-scale image that makes it impossible to advert your eyes. Joan Kaya is also in the show. He adopted a bad drag queen persona and made paintings using nail polish. He has another piece where he uses the ashes of his best friend Charles as the ground for the work and when it is turned over the other side says: “Bitch, I told you I’d be in an exhibition before you.” There is a graveyard humor only people who have been subjected to real trauma can engage.

CM: Are you engaged also with practices of work that are not necessarily producing objects as art? For example, are there any references to the creative strategies used by Act Up and the kind of social and political mobilizations that take place via performance, like drag queen and drag king shows at the time?

JK: Not in this exhibition because it is a portraiture show and delimitated to the frame, but certainly in Art Aids America, my upcoming exhibition, it will be one of the main things we are talking about. I am not going to be doing an exhibition about AIDS activist graphics because that has been done already, but I am very much interested in the window space called “Let the Record Show” that was at the New Museum, which was the first inauguration of the “Silence Equals Death” logo that became ubiquitous. I am also interested in forms of art making that refuted the commodifying system of the gallery at this time.

CM: Can you speak about the culture of war in relationship to the recent removal of David Wojnarowicz’s “Fire In My Belly” from your exhibition “Hide/Seek”? Is this an echo of what happened in the 1980s?

JK: Yes.

Photo by Irit Batsry of a demonstrator wearing a David Wojnarowicz mask during a rally against the censorship in NYC.

CM: Can you locate it comparatively?

JK: In some sense it is totally different, not least because of course in 1989 when Mapplethorpe’s show was killed there was an outcry within the art world, but it was vocal and delimited to exceptional community based galleries. Now, I am struck by the fact that almost everyday I am getting a phone call from one museum or another, across the globe saying they are showing the film and asking what they need to know about it. There really has been a mess enabled by electronic media in a way that was not available in 1989.

CM: Why didn’t they show it before?

JK: That is always the question I want to ask and of course I have also worried that now they are showing the video they will be able to claim they gave it office and queerness will not be part of their regular exhibition program because they will feel they have already included it. That is ridiculous, but to answer your question directly, similarly to 1989, this is not about art in a profound way. It is not even about sexuality, it is about politics and we are seeing the right wing politicize the question of representation yet again, because fundamentally it is their agenda.

The Right, as all ideologues claim, wants to supplant a notion of a pluralistic democracy with an idea of a singular vision dominated exclusively by their perspective. They want to supplant discourse with abject props and look away from precedence, back to a realm of surety in which their particular ethnic grouping was unquestionably dominant. That vision of America is, thank god, dead except within the ideological Right, but they are doing their best to use the politics of representation to weepily bring us back to small town America and its fictive constructs, and to there by soldering an increasingly fragmented movement around an America that never was.

CM: What do you think will be the effects in the long run of the censorship, regarding the visibility of queer culture and the parallel between what is happening in popular culture versus art culture or the possibility for presenting this type of exhibition in government funded institutions?

JK: It is a very complicated question. Let me first say it is not without meaning that this exhibition took place at the Smithsonian, not at a large private museum. Let’s face it, the Met, MoMa, or the Whitney could have done this exhibition and would not have given a damn what congress had to say. They are much freer than a federally funded institution and ironically it was a federal museum that sought to break the boycott, not one of New York’s great, supposedly leading, institutions.

David Wojnarowicz, Fire in My Belly (video still)

Source: http://blogs.seattleweekly.com/dailyweekly/2011/03/david_wojnarowicz_film_is_too.php

CM: What do you mean by the boycott?

JK: Basically, the blacklisting on sexuality from art since the Mapplethorpe exhibition in 1989. Here we are in 2011 and my show is the first major queer show, which is ridiculous after years where queerness is in evidence in the realms of music and film and television and other power centers in American life. Yet the museum world, which understands itself as progressive and is credited as such, is now behind international banking in its political openness.

What worried me was the social and political gesture that was intended to ultimately kill the blacklist has, at least for now, the distinct prospect of having reinvigorated it. It is funny, we will see in the next couple of years whether or not this show had its intended effect, but it has created so much controversy, I am not entirely clicked whether a museum will take sexuality under consideration. In this sense the Right got what they wanted out of this. They want pages, they want commentary, they want to make themselves central to definitions of culture and they have done that. Now when we make exhibitions about ourselves we necessarily must reference or address them. Any museum proposal that goes forward is going to have to talk about what happens when The Catholic League attacks. They achieve this act, not on their own, let us be clear, but because Republican leadership jumped into bed with them as a needs of appealing to a tea party base.

CM: To what extent do you think issues of sexual orientation as opposed to religion caused this controversy? I understand the “infamous” scene is one with ants crawling over a crucifix depiction of Jesus Christ. Is it so much about sex, or is it much more about religion?

JK: It is supposed to be about religion, but anybody who has looked at a broken alter piece knows that the most orthodox history of Christian art understands the degree to which the image of Christ becomes an allegory of human suffering. That is not new, it is ancient, so with the idea that somehow this is disrespectful to Christianity is bullshit and they know it.

Video still from David Wojnarowicz's video Fire in My Belly

Source: http://www.artltdmag.com/?page=news&sec=news

CM: It is censored because of the larger framework then?

JK: It is the larger framework. The show was up for a month before they attacked and I would not be surprised if they did focus groups trying to find a handy way to get it censored. Paradoxically this a certain form of progress because in previous years, you could simply identify a work as queer and it would be killed. They can’t be nakedly homophobic anymore so they find new ways of getting what they want and in America, the discourse of religious offense, which called the work “hate speech,” appropriating our language and using our strategies against us. It is not about religion to be sure; it is not even about our sexuality, it is just about gay power. It is about playing the old game of divide and conquer and building your base by in-common hating. That is a cynical, hateful anti-American politics that has moved alongside other American political developments since the founding of this country and it continues to deliver, which is why they do it. Old habits die hard.

CM: Is it a coincidence that Wojnarowicz’s piece is the one removed from the exhibition after he had been censored in the 1980s? What is the relationship between the mode of production and the strategies that artists like him were using as a form as resistance, activism, and personal expression in relationship to the way that queer artists are working today?

JK: Wojnarowicz very much understood the options for his work discursively to be binary at the moment of Jessie Helms and widespread homophobia in the art world. On one hand you can produce work like Felix Gonzalez Torres which acted, and he uses this term self consciously, “virally” within the museum system to escape censors, to speak queerness within the institution in ways that are illegible to those who refuse to hear it.

Alternatively, you could be like Wojnarowicz where you were a directly aggressive political activist. Wojnarowicz would not be surprised that he is the subject of this controversy, nor would Mapplethorpe have been to find “The Perfect Moment” pulled. It was part of the point of these works to be aggressively political in a legibly forward sense. I think Wojnarowicz may be surprised that his work is still tendentious today, but he would have understood the particular irony that they couldn’t attack the work on its queerness and had to use the rues of religious freedom.

I also think we are at a curious cultural moment in which this poetic post modernism rules the roost and more aggressively political work tends to be given very little respect as an emblem of an old school political investment, one that in mentioning the category that it seeks to contest is unaware of how powerfully it re-inscribes that category as central. I think that is a misunderstanding of a kind of political work today and I am very much interested in forward queer art even as I am also interested in poetic post modernism. When something assimilates itself too easily to the market I begin to get nervous.

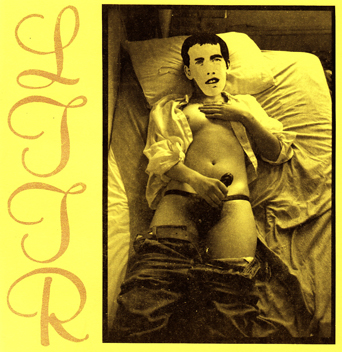

Emily Roysdon, Untitled (David Wojnarowicz Project) on the cover of LTTR Issue # 1

CM: I think there is a relationship between the ways artists are working today with the boom of the market. The market will not tolerate this straight forward political critique that was so present in a time of crisis and which was perhaps the only way to voice the urgency of the moment. Similarly, contemporary gay politics are in a moment of normalization in the sense that the fight does not appear to be about life and death, but revolves around the idea of being able to get married and other institutional rights. What is the work that gets produced within this paradigm of normalization when there is not really urgency; what are queer artists working on today?

JK: I see a lot of work about normalization, which essentially embraces the idea of queerness by playing with the prospect of mutability, either in gender terms or in erotic terms. It is also interesting how many of the aesthetics of resistance or dissonants of the work are now reanimating punk modes and other historical modes of resistance.

Under queerness you really don’t want to claim any kind of essentializing identity or history, so there are gay artists who aren’t invested in queerness because they don’t care or understand it, but there are also queer and post queer artists who are interested in exploring the limitations of the queer discursive frame from a position that understands what that politics was able to proffer and unable to see.

Weblink: Jonathan D. Katz's website

↑Top