Stonewall had a profound effect on me. I would not have been able to predict that a historical event like that could influence my inner feelings so much. I went rather quickly from thinking there was no gay community to thinking there is a gay community, from thinking gays are bad to gays are good, from being ashamed of being gay to being proud of being gay. I always wanted to write about gay subject matter, but suddenly I was interested in addressing a gay reader. In the past gay writers were apologizing for gay life to straight readers. After Stonewall, but not right away, it took ten years; gay writers were addressing other gay people. It stopped being an apology, it became about communication from one gay person to another.

Edmund White

Download interview in PDF format ![]()

An Interview with Edmund White

February 22, 2011

Edmund White’s apartment in New York City

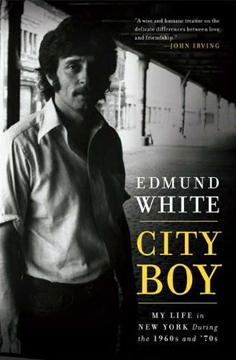

Edmund White: My name is Edmund White. I am a writer and I have written maybe twenty-five books. I recently finished a novel that will come out next year titled Jack Holmes and His Friend, which is about a straight and a gay man who are best friends in New York in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. I am currently working on a memoir about my life in Paris in the 1980s.

Carlos Motta: Where and when were you born?

2009

EW: I was born in Ohio in 1940 and lived there until I was seven.

CM: Where did you move?

EW: Because my parents were both Texans we went to Dallas, but my mother was very restless and she would move every year so we moved all over the Midwest and Texas. When I was fourteen I went to boarding school in Michigan and then I went to the University of Michigan.

CM: Is Michigan where you came out as gay man?

EW: Actually, I came out very young, at age twelve, even before going to the boarding school in Michigan.

CM: How was the experience coming out at such an early age? What kind of world did you encounter in 1952 when you were coming out?

EW: I think my experiences were fairly bizarre or at least certainly a-typical. Some of my first gay experiences were with hustlers in Cincinnati. I had a little summer job working for my father and I would use the money I earned to rent a hotel room and hire much older men to have sex with me. I did that all of the time as a teenager because I could not figure out any other way to have gay sex. I also had sex with the neighbor boy but he was reluctant. I had sex at summer camp with other boys and then eventually I had sex with boys at boarding school. As early as thirteen or fourteen I was having sex with people I met in public toilets, mostly married men who were terrified of me. Our laws make it very hard for young people to see anybody more than once because you are “jail bate,” so nobody wants to date you or give you their phone number. There is no continuity in the sex life of a teenager.

1982

CM: It seems like you were a precocious sexual person.

EW: I was precocious in every way. I was very intelligent and wrote a novel by the time I was fourteen. I was a singer, head of the glee club, and got straight As. I was not athletic, but I was a dancer, and I danced a lot in high school productions.

CM: Despite your own sexual practices, how were you thinking of homosexuality and how was it presented at the time? How did you fit into the paradigm of the moment?

EW: I thought it was a very bad thing, maybe something slightly glamorous, but bad. I wanted to go to a psychiatrist to be cured, so by age sixteen I was going to a psychiatrist three times a week. I had to tell my parents I was gay in order to get them to pay for the psychiatrist. I always knew I wanted to be a writer and I thought that if you were homosexual and a writer, you would be so limited that nobody would want to read your books, which is sort of true.

CM: What was your experience of homosexual writers at the time? Were you looking for this kind of content in the books that you were reading?

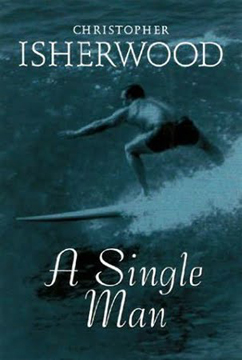

EW: There was Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice and Andre Gide’s Journals. Eventually in the 1960s there were other things like Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man and cheap books sold under-the-counter that were pornographic, not with pictures, but with text.

CM: In Death in Venice, how did you relate to the gay character that is over-determined by drama and death?

EW: I think almost all the fiction of that period was very homosexual. I related to the idea that homosexuality was bad, but also very glamorous because it involved rich people, doomed people, death... There were novels about, like Quatrefoil and Finisterre, and they were about beautiful young men who met each other and lived in some remote place, like a cliff overlooking the ocean, and they would commit suicide. I think it definitely felt like a very doomed, bad thing.

1997

CM: When did you start to think about writing about gay issues? When does it become a priority for you?

EW: Right away. At age fourteen I wrote a novel called The Tower Window about a boy who is in love with a girl, but is also fascinated by a Mexican man whom he has sex with. When the girl rejects him, he flings himself at the Mexican man. I had never read such a novel. I invented the genre because it was not pornographic; it was serious and tragic. At that point, nothing I had read was about contemporary American life with gay content.

CM: What about work in other countries? Were you following the path of any international writers?

EW: As a Mid-Western schoolboy there were not many chances to hear about those books. The odd thing was that books that had no transparent gay issues were very appealing to gay people. I am thinking of Hermann Hesse’s books, specifically Steppenwolf, which is about an alienated person who always contemplates suicide and is comforted by the idea that he has an escape from this terrible world. This is something I think many gay people could identify with.

CM: The representation of gayness at this time was relatively tragic, a kind of doomed experience. Were there any positive representations of homosexual life, maybe not in literature, but perhaps in the movies or elsewhere?

EW: I lived in a boarding school. We saw only the movies they showed us every Saturday night in the gymnasium. My parents did not approve of movies so I was never allowed to see a movie before boarding school; my experience of movies was very limited. There was no Netflix or television so the chance of encountering anything other than standard Hollywood comedies was unlikely. I remember though that in some of those comedies there was a little hint of homosexuality. For example, Bringing Up Baby, did you ever see it? I think it is a Cary Grant movie; he wears a dress and uses camp language. There were movies like this, but I would never have been shown a movie like that at the time.

CM: When you wrote your first novel The Tower Window at age fourteen, did you publish it?

EW: No. I did not really try to get it published.

1977

CM: Was the experience of writing something that you were doing for yourself or were you already thinking of constructing an audience and readership?

EW: I never did it for myself. I have never understood writers who say they write for themselves. The only way I can write is imagining the impact that my writing will have on a reader. There is a kind of criticism called “reader-oriented criticism,” I have never read anything about it, but it makes sense to me that you would want to know how you influence the reader. I teach creative writing and what I like about teaching a group of people who have all read the same stories by each other is that you get a lot of reader response.

CM: What is the first book you published that had a readership and that established you as a writer?

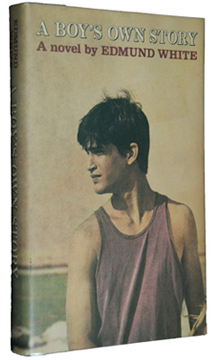

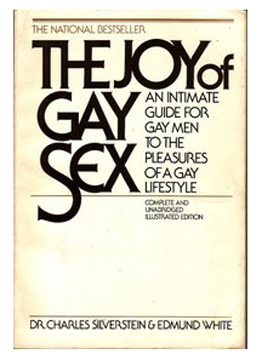

EW: My first novel was Forgetting Elena and it was well received. Even Nabokov said it was his favorite American novel, which was a good compliment. Still, it was small; it did not sell many copies. My next book, Nocturnes for the King of Naples was my first gay book, and it had a small gay following, but the book that had a huge readership was The Joy of Gay Sex. States of Desire: Travels in Gay America was a book that received a lot of press attention and the one that made my name was A Boy’s Own Story.

CM: Before we speak in depth about some of the books, I would like to ask you when you moved to New York. Was it after you finished college?

EW: Yes, in 1962.

CM: What was New York like at this time?

EW: It was very exciting. It was very different because now the Internet rules everything and there are not very as many face-to-face encounters. Back then everything was done on the street because there were virtually no gay bars. The mayor had closed down all the bars to clean up the city for the World's Fair. You walked down Greenwich Avenue or Christopher Street at any hour and there were tons of gay men cruising each other. You had to be good at that, but there were thousands of people and it was very exciting. The very first night I was here a friend of mine took me to a gay restaurant and the idea of a gay restaurant seemed remarkable to me. I knew gays would go to certain places in order to meet each other to have sex, but I couldn't imagine this cursed group of people would of ever want to socialize together.

1980

CM: You never previously envisioned it as a kind of community or communities?

EW: Not at all, I had no community feeling. If I had been in a building having sex with other men and as I walked out the building caught on fire, I wouldn’t have even turned back to say “fire.” To me, these people were not friends, anybody I liked, or anything. There was so much self-hatred. I was still going to the psychiatrist.

CM: This suggests you considered being a homosexual as exclusively a sexual act?

EW: Yes.

CM: It did not have anything to do with kinship, partnership, or friendship?

EW: I did actually have a lover and he is why I came to New York. This boy I was in love with came here, we lived together almost immediately, and we stayed together for seven years. Still, we did not know any other people like ourselves. We both worked for Time Magazine and you could never say that you are gay at work. I would not dare go by his desk too often.

CM: Was cruising on the street also a secret act?

EW: It depended on the place. At midnight on a Saturday night, Greenwich Avenue and Christopher Street would be full of people all cruising each other and it was okay to do. But there was always the possibility you might pick up an undercover policeman who would arrest you.

CM: Was it common to get arrested?

EW: Not too common. It had been where I lived in Michigan. At the University one of my best friends was entrapped by a plainclothes policeman and had to spend the next seven years seeing a psychiatrist once a week. He was on parole for seven years just for touching somebody’s penis in a toilet!

Christopher Street in 1979

Source: http://www.outgay.co.uk/pics.html

CM: Do you remember when homosexuality was decriminalized in the United States? Was it in 1972?

EW: It was never decriminalized throughout the United States; it was only state-by-state. As far as I know there may still be some states where it is illegal. When I was growing up it was still a capital punishment crime. In Georgia, you could cut somebody’s head off for being gay.

CM: Where else in New York was gay cruising happening?

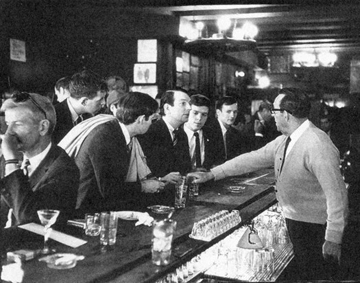

EW: Primarily in Greenwich Village. You would go to Times Square where there were shops that sold pornography, but they were always being raided and closed, same with the bars. Maybe around 1966 or 1967, some gay bars began to open. The one that always survived was Julius. It had weird and strict rules sometimes depending on the year. At one point you could not stand at the bar facing the bar, you had to stand at the bar looking out toward the windows because I think they were afraid the police would walk by, see all these men touching shoulders and think that they were maybe touching each other. Even on Fire Island you could not dance with another man even if there was a group. In every group of men dancing, there had to be at least one woman and a guard sat on a very high ladder with a flashlight and would point at people when he suspected there was no woman in the group.

CM: During the 1960s did you have relationships with lesbian women? Was there already a kind of community identification or was it a different situation for women at the time?

EW: One of my closest friends was a lesbian and I was engaged to her briefly. We are still best friends sixty years later. She came to New York at the same time I came so through her I met other lesbians I don’t think I would have met otherwise. I met her when I was fifteen and I did not know she was a lesbian and then gradually we became close and got engaged. I realized she was a lesbian, I was gay, and we went our separate ways. I do not think gay men would have gone to lesbian bars. I went with her sometimes to The Dutchess. There were several lesbian bars in the 1960s, but they were not as badly treated by the police as gay bars.

Julius Bar in 1966

Source: http://lpbarretto.blogspot.com/2009/11/five-ways-to-change-world.html

CM: Can you tell me your experience and memory of Stonewall? What happened and how did you relate to these events?

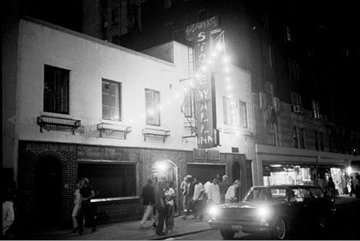

EW: I had a friend called Charles Birch who was a very fiery activist and leftist. I was a rather conventional person, but we were walking by The Stonewall at the very moment when it was raided. We were not inside but we witnessed the customers being dragged out of the bar, put in a Black Maria, and taken away. Some police stayed behind to guard the remaining people because there was not enough room in the paddy wagon for all of them. Most of the people who were arrested were the staff members, but some clients were arrested too. What was remarkable about the experience was that instead of running away and just tying to vanish, which had always been the case for gay people, we rebelled. I think it was for a number of reasons; Judy Garland had just died, it was an extremely hot summer day, and the clients at the bar were mostly Black and Puerto Rican. In Greenwich Village these people were called “A-trainers” because they were ghetto kids who took the A train down to the village. They were more accustomed to fighting with the police for other reasons and because all the bars had been closed for so long and now seemed to be reopening, the act to suddenly want to close this bar terrified everybody.

CM: This kind of raid and police brutality was common?

EW: Oh, yes.

CM: It happened all the time?

EW: All the time.

CM: So Stonewall was the point in which people just could not take it anymore?

EW: That is right. It was partly because there had been an unspoken amnesty for maybe two years where bars were not being closed and raided because we had a new Mayor, John Lindsay, who was a fairly liberal Republican. He left the gay community alone. The Stonewall was a mafia bar and I think the real reason they raided it was because they suspected drug dealing was going on. It was also very unsanitary with no source of running water behind the bar; they would take old glasses, wipe them out and serve again, it was really disgusting.

I think historical rebellions like that are always for the wrong reasons, like when the people destroyed the Bastille; there were only four prisoners in it. There is always some wrong reason, but why not?

The Stonewall Inn Bar, 1960s

Source: http://jonjost.wordpress.com/2009/11/

CM: How did Stonewall and the period after influence your writing?

EW: Stonewall had a profound effect on me. I would not have been able to predict that a historical event like that could influence my inner feelings so much. I went rather quickly from thinking there was no gay community to thinking there is a gay community, from thinking gays are bad to gays are good, from being ashamed of being gay to being proud of being gay. I always wanted to write about gay subject matter, but suddenly I was interested in addressing a gay reader. In the past gay writers were apologizing for gay life to straight readers. After Stonewall, but not right away, it took ten years; gay writers were addressing other gay people. It stopped being an apology, it became about communication from one gay person to another.

CM: Did you and your peers recognize Stonewall as a historical event right away?

EW: Yes, it was very clear. It was not two days later, but maybe two weeks later, because there were many articles about it in The Village Voice, The East Village Other, The Eye, and other little leftist magazines. People wrote articles about the significance of it as it happened.

CM: Did you write anything in particular about this?

EW: I wrote a letter that became famous because it is one of the few documents that still exists written by an eyewitness. My friends Alfred Corn, a gay writer, and his wife at the time, Anne Jones, were away for the summer on the West Coast and I wrote them a long letter about what I had seen the next day or two days after the event.

CM: At what point do you start to think of your writings, especially the deeply personal books like your autobiographical novels, as having some kind of political content?

EW: I think every gay writer in the early 1970s was very aware of the possible political content of his work. Because of the almost Stalinist tenure of the gay literary community, there were many gay critics suddenly and they would take writers to task for being politically incorrect, they didn’t use that term, but they would say you were not presenting positive role models. There was this idiotic idea that you had to present gay characters in a positive light, which was completely a-historical. It went against any intelligent point you might have been trying make. You would not want to show a gay character as being liberated, happy, and positive in a period when he was oppressed. Why would you bother to have a revolution?

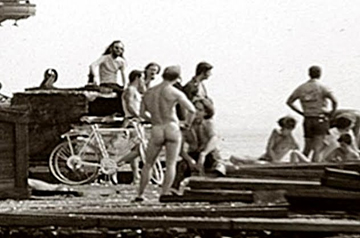

West Village Piers in the 1970s

Source: http://www.back2stonewall.com/2010/02/1970s-gay-history-christopher-street.html

CM: How did The Joy of Gay Sex, a project that is about a gay audience and for a gay audience, come about?

EW: The English publishing company Mitchell Beazley had packaged and published The Joy of Sex by Alex Comfort and it was a huge success all over the world selling millions of copies. They wanted to repeat their success or at least a small part of it, by having a Joy of Lesbian Sex and a Joy of Gay Sex. I had to audition for it; there were maybe ten writers who had to submit samples as well as psychiatrists because the idea was that you would be teamed with a doctor. I won the competition.

CM: Was it supposed to be a gay doctor?

EW: It was my own psychiatrist. He was gay. After Stonewall I made the great leap forward of seeing a gay psychiatrist because my idea was now that I would be gay, I didn’t want to be straight, but I wanted to be happily gay and sort out some of my personal problems. With the book he quite ethically told me I could not be his patient and collaborator. I was broke and needed money so badly that I stopped being his patient. That book was very successful. People made fun of me for writing it, but Americans love money and anything that makes money they end up by respecting.

CM: Who was making fun of you? Your intellectual peers?

EW: Yes. They thought it was a trashy book.

CM: What kind of impact did it have for you and the way that you thought of writing and gayness?

EW: There were so many people out there who were uninstructed and suffering, like a seventeen-year-old boy living in a small town in Missouri, so the idea that you could actually reach and reassure these people was interesting, I liked it. When I wrote States of Desire, I wanted to travel and actually meet some of these people. When I wrote A Boy's Own Story I wanted to show an in-depth portrait of one of these people, although it is fictional.

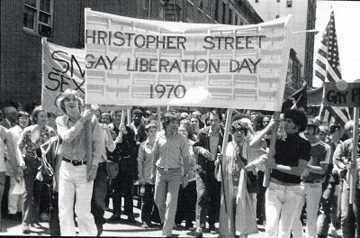

Gay Pride March, 1970

Source: http://counterlightsrantsandblather1.blogspot.com/2009_06_01_archive.html

CM: When you started writing A Boy's Own Story, did you know it would be a long-term project followed by two more books?

EW: No, I didn’t. I thought it was a one off and then when it was a success I realized I could continue the story because there were other interesting things to tell. A Boy’s Own Story is a fairly gloomy look at a teenager who is very conflicted and not happy in the 1950s. I decided to write about that boy coming to New York and having a gay life, but still being very conflicted. The book ends with Stonewall. It is actually a very strong political statement at the end of the novel, which was not popular among serious novelists in those days. As I approached the end of the book I kept debating with myself whether to put that in or not. I thought of Stonewall as the single biggest thing that ever happened to me so decided I might as well put it in.

CM: What is the balance of autobiography and fiction in this series?

EW: There is quite a bit of fiction in them. As I mentioned to you I was very precocious sexually, but the boy in A Boy’s Own Story is not at all. I was afraid that if I showed a freak like myself having sex with two hundred people by the age of sixteen people would not be able to recognize themselves in the character and think he was sick and should go to a hospital.

CM: You were concerned about the gay reader, not the straight reader judging?

EW: Either one. I thought that nobody would be able to identify with this person whether straight or gay.

CM: At this point have you already established a network amongst other gay writers, be it nationally, or internationally? Is there a community starting to be formed?

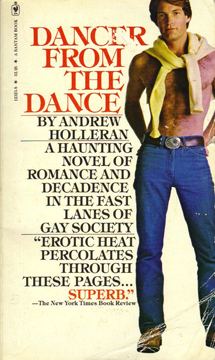

Andrew Holleran's Dancer from the Dance, 1978

EW: I belonged to a writers' group called The Violet Quill, which was sort of a joke. There were eight of us initially and we met over a two-year period during the late 1970s and early 1980s. We would read to each other and it was very exciting to have a group of peers listening to chapters from your book. I was working on A Boy's Own Story in fact, and I think it was here we each figured out our turf. Robert Ferro was writing about a gay man who was trying to force his family to accept his lover just as they accepted their daughters and sons in law. It was a very fiery Italian American family he was writing about with high emotions, so that was exciting and interesting. I guess in a way we never discussed it, but I think we thought about what each of us was doing. I was left with Childhood and Andrew Holleran, who wrote Dancer from the Dance, was left with Fire Island and glamorous New York life. We sort of divided up the world.

CM: You did not write about your life in the 1970s until last year, correct?

EW: Yes.

CM: Can you describe this period of your life and living in New York after Stonewall as a gay man?

EW: It was a very poor city. It was almost bankrupt and there were very few services. The garbage people and the police were always on strike and everything was falling apart. There was what they called “white flight,” white people leaving Manhattan for the suburbs, and there was very high crime rate and a lot of drug addiction. Those are all negative things, but they meant rent was cheap and you did not have to work too hard to earn enough money to live in Manhattan. My neighborhood, Chelsea, is now very gentrified. Back then it was dangerous to walk through here; there would be black and Puerto Rican men sitting on their stoops, they would throw bottles at you, they had ghetto blasters, and would play loud music. The buildings were very ugly, there were no trees on the street, and everything was very different. The buildings were once quite nice, built as middle-class houses in the 19th century, but everything had become very run down.

This was what was also exciting about New York; it was a very edgy city. Suddenly there were many gay bars where there had been none in the 1960s. Now there were back rooms too, which there had never been before. There were the piers, these abandoned docks that stuck out into the Hudson, where people would go and have sex in these big huge abandoned buildings. People would also get up inside the parked trucks under the West Side Highway and have sex. There was a lot of outdoor anonymous sex and this was an interesting era because it was after the invention of antibiotics, but before the advent of AIDS, so it was a small window of humanity, of history, where people were free to do what they wanted to sexually. There were basically no fears about the consequences of sexual acts, even for straight people, because there was birth control and legal abortion, and antibiotics for diseases like syphilis. There was no AIDS so there were not tragic consequences for sex acts.

1964

CM: One of the things about your recent book City Boy that stuck with me is your description of different types of relations you had that played different roles in your life, which gestures toward an idea of split kinship and ruptures the idea of a singular monogamous relationship.

EW: Yes, we looked down on monogamy and I think the gay leaders of the 1970s would be appalled to see how many gays now want to be married and monogamous. Pre-AIDS, the idea was to be free, overthrow the heterosexual model, and try to invent something new. Part of that was to separate out the various functions that accumulated in a relationship with one person in heterosexual companionate marriage that, we thought, did not work. It was ending in divorce; it was a disaster.

We thought you should have “tricks” for one night stand for sex, “fuck buddies” you would see on a regular basis for sex, a “lover” who might be somebody you would live and have a physical relationship with or sleep in the same bed and kiss, but maybe not have sex or just occasionally, etc. I think a lot of gay life is still being lived this way, but I think gays have become so prudish that they do not like to admit it anymore. We thought it was a positive experiment, I think AIDS changed all that.

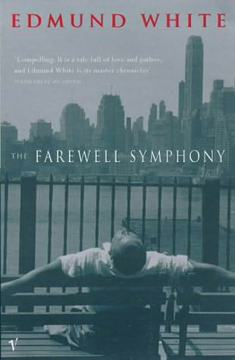

CM: Can you speak about AIDS and its consequences to your work?

EW: I wrote The Farewell Symphony. Its title is based on a Hayden symphony where all the instrumentalists get up and leave the stage, one after another until only one is playing at the end.

CM: Was that a metaphor for AIDS?

EW: For AIDS and the way I experienced it. I felt that everybody in my life was dying. Right across the street from where I live is a building with a historical plaque in front of it. It is where we had the first meetings of Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1981. My name is on the plaque because I was the first president of the organization, which is still the largest AIDS organization in the world.

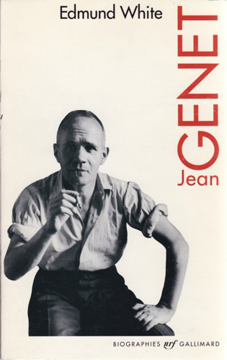

I think at first it did not really respond to the AIDS crisis. From 1986 on, I was working on my biography of Jean Genet and real AIDS activists like Larry Kramer were always angry with me. He would say: “Why are you working on that stupid thing when we need you to write about AIDS,” but I felt like gay culture was in danger of being reduced to just one thing, the sickness, so I chose to write about a gay culture hero in the face of the epidemic, which had become so reductive. There was AIDS and that was all; when people thought of gay people they thought of AIDS. We who had been medicalized before and escaped that medical definition of homosexuality were now in danger of being re-medicalized. It was important to resist that. I think the first thing I wrote about AIDS must have been around 1988. It was a little book of stories I wrote with Adam Mars-Jones called The Darker Proof. It was published in paperback in England and included stories by us both. Even at that date there was virtually no gay fiction about AIDS being published. When you would watch television, the people talking about AIDS would be a doctor, who was not gay, discussing this terrible condition. It was important that gay writers tried to show AIDS from within; what it was like to live with it.

CM: You did not employ writing as a form of political activism directly along the lines in which other people were?

EW: No, not at all. One of the reasons I moved to Paris was to escape all of this. I had been the first president of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and I hated it. I did not like myself in that role and I did not like the idea of devoting all my energy to AIDS activism. I am good at writing, and writing always has some political import in the sense that you are reflecting people’s experience and showing how a gay man experiences AIDS. I ended up writing quite a bit of literature that has to do with AIDS. The Married Man is an AIDS novel and The Farewell Symphony is all about people dying of AIDS.

Verlaine and Rimbaud in a painting by Henri Fantin-Latour of 1872

Source: http://dejesusmarcelo.blogspot.com/2008/07/jai-seul-la-clef-de-cette-parade.html

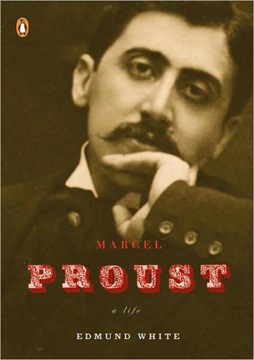

CM: Can you speak more about your biographies of Arthur Rimbaud, Jean Genet, and Marcel Proust? How did you approach that work?

EW: I wrote about Rimbaud, Proust and Genet, three men I would call homosexual. Rimbaud maybe the least so because he seemed to give it up after a certain age the way he gave up poetry. Although, we do not know when he lived in Africa if he was gay or straight. In any event, the only reason we know about Rimbaud is because in the most significant period of his life, between the age of sixteen and nineteen, he was a great poet.

CM: And because of his relationship to Verlaine…

EW: That is what the legend is really about. Verlaine was clearly bisexual; he always had women and men in his life. I was very criticized for my little Proust biography by Roger Shattuck and other important Proust scholars in America. As if I made it so gay and he was not really gay. It is probably because heterosexual critics who have invested their whole lives in writing about Proust don't want him to seem less universal, and if you call him gay it seems to threaten his status as a great universal writer, that is what they think.

CM: As if the impact of his sexual orientation or identity would not mark also the way that he was writing?

EW: Exactly. Proust wrote a very interesting letter to the editor of Gallimard, which instructed him to publish the book because it is the first important book about homosexuality. He says it in so many words and yet people conveniently forget that letter and that he calls it an autobiography, although it is clearly a novel.

CM: Throughout your writing career have you faced rejection or discrimination from the literary establishment?

EW: Constantly, but I must point out that the most violent critics, who look down on my work for being so homosexual, have been other homosexuals.

1999

CM: Why do you think that is the case?

EW: I do not know. I think I have had seven long hateful reviews in my life from people who obviously wanted to destroy me, and they were all gay men.

CM: Is the literary establishment itself a homophobic institution?

EW: I think it was in New York more so in the 1960s than it is now. It was very Jewish in the 1960s and I think that the Jews of the generation of Norman Mailer and Saul Bellow, were fairly liberal and probably would have worked for gays rights and to end persecution of gays, but I think personally they were freaked out by male homosexuality, I don’t think they liked it.

CM: I am struck by the idea of the universality of literature because it presents itself as a monolithic institution that lives outside of the social conditions around it. Do you have any thoughts on that?

EW: “Universalism” was an idea the French invented in the 18th century and it was a very progressive idea at the time because it basically said a black woman from the Antilles and a white man from Paris are the same, they are both individuals and they are citizens. The kind of universalism of that period was very progressive. Now, when people use the word “universal” it is almost always reactionary because they are really trying to say that if you are not writing about a white heterosexual man, then you are not writing about something universal, your work is too particular, you are only writing about a Chinese Lesbian, for example, and who could possibly care about that? Straight male critics still dominate the literary field so the reception of literature, whether it is in universities or critical establishments are still informed by these tastes and prejudices, that are defended by being called “universal.”

CM: When you look retrospectively at your life and your body of work, how do you feel about it?

1993

EW: I feel good about it, I have written some good books. Except for The Joy of Gay Sex, I have never done anything that was commercial, or written anything that was designed to capture a market only. I try to hold myself to the highest artistic standards. As a result I am very poor and not very well known. I think I might have had a bigger career if I had been more easygoing or compromising, but I feel good about this. I think because my father was rich (although I never inherited any money because he gave it to his second wife) this gave me a kind of class confidence that I think was important for me in being able to be a pure artist.

I just wrote an essay about Christopher Isherwood, so I am thinking about him. When you ask how he came to write A Single Man in the 1960s, which is really the first openly gay text about contemporary life that has no ideology or apology, but shows him moving around in the normal world and being open about his homosexuality with his heterosexual friends, I think you have two or three answers; he participated in the first gay liberation movement in Berlin in the 1920s and he had a kind of class confidence. He was of the English gentry and I think they have always had a sort of “I can say anything I want to” attitude.

CM: What are your thoughts on aging as a gay man?

EW: I have been very lucky because in the 1950s we used to have a funeral for gay men when they turned thirty and I always thought maybe I could stretch it out to forty. When I got to forty, I thought maybe it could be stretched to fifty. Now I am seventy-one and it seems like I have as much sex as I ever did. Most of that is thanks to the Internet where you can find these highly specialized markets, like attractive people who like older men, even chubbier older men, it is all very organized. Before the Internet I never could have found these people.

Weblink: Edmund White's website

↑Top